In his book Jesus was Caesar, from which I obtained much of the material in Chapter 2, Francesco Carotta advances two hypotheses. The first is that Julius Caesar was the template for Jesus Christ. One JC gave rise to another JC1. The second hypothesis, which I found ultimately unconvincing, is that the substitution happened more or less by accident due to an accumulation of copying errors.

In Carotta's description, during the long historical game of telephone the errors built up to the point that the story became unrecognizable, and in one forgotten corner of the empire the imperial cult of Divus Julius mutated into the Church of Jesus Christ, which then proceeded by a process of proselytization and religious intolerance to eradicate the cult that had given birth to it in the first place. Carotta bases this hypothesis on a few correspondences in names (e.g. Gaul/Galilee, Corfinium/Cafernaum, Junius Brutus/Judas, and so on), but there are a great many others where the names assigned to the corresponding characters or places are not at all similar (e.g. Pompeius/John the Baptist, Cleopatra/Mary Magdalene, Rubicon/Jordan), in which it's very difficult to see how a couple of mistakes by a weary scribe working by candlelight to copy a smudged manuscript could lead to such a large orthographic change. To be fair to Carotta, he draws upon a lot of fascinating details regarding e.g. how Latin was rendered in Greek and vice versa; the errors that can be introduced by the lack of punctuation or even spaces between words; the confusion that can arise from the heavy usage of acronyms and initials (which might have had a commonly understood meaning by whoever wrote them down but be utterly obscure to someone a century or two later); uncertainty that can arise from texts that might be read right-to-left or left-to-right (this not having been standardized at the time); as well as substitution of titles in various languages for proper nouns, and vice versa. As you might gather from all of that, the written documents of the era were a hot mess.

All that said, it seems unlikely to me that copying errors could lead to people en masse simply forgetting things that completely, especially while memory of the historical Caesar continued very much unimpeded. While it's certainly true that any one manuscript chain would tend to accumulate mistakes, there are multiple chains taking place all over the empire, all of which can be used to check against one another and correct the most egregious errors. The pronunciation of names certainly changes over time (e.g. the Latin 'yoo-lee-us kai-zar' vs. the English 'joo-lee-us see-zer' for Julius Caesar), but it rarely happens that we forget who we're talking about entirely.

If that were all there were to Carotta's scenario, it would have an element of 'thousand monkeys' theory to it, in which a complete narrative emerging more or less from random noise2. That isn't entirely true: Carotta also suggests that certain editorial changes were made by local priests in order to tailor the story elements to be more relevant to their flocks, hence for instance moving the locus of the action to the area around Judea, or substituting Jesus' ability to cast out demons from their possessed victims for Caesar's propensity to lay siege to and then liberate cities3. The history of Christianity shows many similar examples of this kind of adaptation, with missionaries to the northern barbarian tribes recasting Jesus as a brawny warrior battling Satan, or those to the Indians of the New World re-interpeting Jesus in terms more familiar to their animisic religion. Likewise, Jesus is generally depicted as having a similar racial phenotype to those of whatever people are worshipping him, However, even with that, this scenario relies upon an essentially accidental forgetting of the original story, which then somehow displaced the imperial cult in the wider empire.

I just don't buy it. I don't think this could have happened by accident.

I think the switch was deliberate, and very probably carried out for political reasons.

Exactly what the motives were is necessarily speculative; it's not like the people engaged in clandestine social engineering are going to write down their plans, since telling everyone that they're making a fake cult sort of defeats the purpose of making the cult in the first place4.

However, I think there are enough other pieces of the puzzle out there that a plausible sequence of events can be guessed at.

Joseph Atwill's Caesar's Messiah advanced what he calls the Flavian conspiracy. Essentially, the Flavian emperors were faced with the problem of pacifying the restless province of Judea, which due to their rigidly exclusionary monolotry refused to acknowledge the imperial cult or, for that matter, imperial rule. Atwill's suggestion was that in order to defuse this resistance, the Flavians decided to invent a new religion to pacify the Jews. Because people are lazy and work with what they know, it only makes sense that they would have taken the imperial cult and its primary cultic figure, changed the names of people and places to better match the local culture, and then sent in their men to start the work of conversion. They threw in other things as well - Jesus' nature as a demigod, his status as a dying-and-rising god, and so on - that don't appear anywhere in the Old Testament but are all over European paganism. I should emphasize here that Atwill doesn't make any identity between Julius Caesar and Jesus Christ; rather, Atwill suggests that Jesus was modelled on the emperor Titus Flavius.

The idea of faking a religion for social engineering purposes isn't quite as nuts as it sounds5. This is precisely the strategy Plato advocated in his Republic, and Russell Gmirkin has written several books laying out the evidence that the Jewish religion as we know it was itself entirely fabricated by priests inspired by reading Plato, who successfully ran exactly that psyop on their own people. Briefly, Plato's idea was to put all of a society's laws in a sacred book, which comes packaged with a manufactured history in which, crucially, the laws come from a divine source. After a generation or two of lethally shushing anyone who publicly questions the veracity of this new book, and raising the children to believe it to be 'God's honest truth', cultural memory of the real history will be extinguished, and the religious laws will be firmly embedded in the social fabric, thus resulting in an extremely stable theocratic republic. The real power would held by the philosophers, who knew the real history, and would initiate a carefully selected few into those mysteries; Gmirkin's take is that the Judean priests realized that they didn't really need the philosophers once the system was implemented, and so their particular experiment in creating the Republic failed (at least from Plato's perspective). If Gmirkin is right about the origins of the Jewish Torah, there's a good bet that this was known to at least some of the empire's more educated philosophers, who would be aware that it had worked quite well. If it had worked well once, why not try it again? Especially when you're just replacing one fake religion with another.

That brings us to the Gospel of Mark, which is held by many to be the first of the gospels. It's worth emphasizing that this is not the formal position of the church, as Christian tradition is that Mark is a derivative work composed some time after Matthew. Rather, the primacy of Mark is a hypothesis advanced by textual critics of the 19th century and after, who pointed out that Mark is the shortest and simplest of the Gospels. If the Gospels are literary rather than historical documents, one would expect the first narrative to be the most stripped down, with later narratives being elaborations of the original. Action Comics Number 1 didn't mention anything about Superman's Fortress of Solitude, for instance.

If you read the Gospel of Mark in the context of the religious and political world in which it was written, it strongly resembles a biting satire aimed at deflating precisely the people with whom the Romans were struggling, namely the Zealots. Historian of the weird Laura Knight-Jadczyk demonstrates this in great detail in her dense, heavily researched tome From Paul to Mark. A lot of what follows is taken from there. To put another way, it's a massive condensation and oversimplification of Knight-Jadczyk's detailed and very careful analysis.

The first thing to note is that Mark depicts the apostles as blundering, obtuse buffoons: Jesus is constantly having to explain to them the meanings of fairly obvious parables, and no matter how many times Jesus tries to beat it through their thick skulls that he hasn't come to win a war for them and sit on a throne built of the skulls of his enemies they can't seem to get it. Worse, the apostles are lazy cowards constantly shirking their responsibilities: they fall asleep in the garden of Gethsemane, they deny him when questioned by the authorities, and finally they abandon him to his fate on the cross after the worst of them, Judas, sells him out to the man for a handful of silver.

The apostles don't come off very well. At least two of them - Peter and Judas - seem to correspond to actual historical personages, in particular known leaders of the Zealots.

Judas is a particularly interesting case, as this is the name of the actual Messiah the Zealots expected to return at the head of an angelic host and lay waste to the world on their behalf. According to Josephus, that Judas was basically a terrorist leader. He seems to have been executed around 19 AD, very probably by Pontius Pilate6, and very probably by crucifixion. Notably, Josephus' account never mentions how Judas of Galilee was executed, despite that he plays a prominent role otherwise; it does, however, mention that his sons were executed in the traditional Roman fashion (i.e. crucifixion) about 20 years later. It doesn't seem accidental that, in the aftermath of the disastrous Jewish War in which Judas and his angelic strategic bombing campaign conspicuously failed to devastate the human species, Mark would give his name to a character with a starring role in betrayal and villainy. Just, you know, to rub the Zealots' faces in it ... and to give listeners a good cathartic laugh at their expense.

As to Peter, this seems to have been a reference to a contemporary of Paul's, who headed up the Zealot faction of the early Christians - which is to say, apocalyptic terrorists who recognized Judas as the messiah.

Jesus spends Mark's narrative wandering about Judea flouting every Jewish law He can get His holy hands on, pronouncing casual heresies and blasphemies that would have struck any Zealot as obscene, giving the legalistic pharisees seizures of embarrasment as He points out their hypocrisy and demonstrates their intellectual inferiority by continuously flummoxing them, and ultimately states outright that He has come to liberate the Jews from the Jewish Law itself. His life is a symbolic dissolution of the exclusive covenant between Yahweh and the Jewish people that bound them to his7 rigid law, and thereby placed them under the exclusive control of the priests. At the end, having been rejected by the Jews, He tells His followers that the Jews are no longer the Chosen People, but that rather, the Chosen are whoever joins His Church ... and that they can come from anywhere. In other words, the Jewish law is repealed, the ethnic exclusivity of the Jewish relationship with Yahweh is undone, and they are invited to join the larger community of man ... which is to say, the empire.

It's interesting that the first person to recognize Jesus as the Son of God was a Roman centurion. Symbolically, this may be a way of telling the audience that the Romans know who Christ is, and recognized Him before the Jews. The fact that it's a centurion and not, say, a random Roman merchant, makes an association with the legions; notably, the cult of Divus Julius was especially popular among the legions, with Caesar's veterans carrying it to the far corners of the empire.

There's also all that stuff in Mark about turning the other cheek, being meek and humble, and of course rendering unto Caesar what is Caesar's and unto God what is God's. All of that is pretty obviously nice to put in there if you want to deradicalize resentful natives following a nasty war. Alternatively, it can be seen as very practical advice for a defeated people whose best interests are in keeping their heads down in the midst of the smoking ruins lest they attract the attention of twitchy legionaries.

Put it all together, and Mark is basically telling his listeners to stop being jerks, stop listening to the idiot Zealots that got their country destroyed, stop listening to the stupid priests and their stupid laws, stop slicing up their baby boys' boy parts8, and rejoin the rest of the civilized world like adult human beings.

One thing I haven't seen anyone comment on is the name chosen by the pseudonymous author. Why Mark? It was quite a common Roman name - Marcus means consecrated to Mars, and the god of war was kind of a big deal to the Romans. It could well be that simple. However, the possible association with Mark Antony seems too obvious to ignore. In addition to being Caesar's right hand man during life, after his death Mark Antony became the first flamen Divi Iulii, the first high priest of the cult of Divus Julius. If anyone stood in relation to Caesar as the apostles stood to Jesus, it was Mark Antony. It could be that the author's nom de plume was a subtle wink to the audience9.

Now, the keen-eyed among you will have noticed that Mark's Jesus isn't a world-straddling conqueror a la Julius Caesar, but an itinerant teacher and healer. How do you turn one into the other? The healer part isn't necessarily as out of character as it sounds for a Roman emperor. The founder of the Flavian dynasty, Vespasian, encouraged stories about his magical healing powers for propaganda purposes. After reducing the Jerusalem temple to smoking rubble, he also claimed - with the help of Josephus, the Jewish Zealot turncoat Vespasian enlisted with writing the history of the Roman-Jewish War - to be the Jewish messiah. Vespasian wasn't even the first gentile ruler to claim this title: the Persian emperor Cyrus was also declared to be a messiah, so there's precedent.

Still, that leaves the 'teacher' part of the equation.

That's where Paul comes in.

There are good reasons to believe that Paul was actually the first Christian in the modern sense10. Rather than a Johnny-come-lately who joined up after Jesus' death, Paul was probably active more or less around the time that Jesus is supposed to have been conducting his ministry, which is to say in the 30s A.D. Now, all we have of Paul are his letters, and not even the full letters - they're edited versions, with obvious deletions, obvious insertions, and not-so-obvious deletions and insertions. Dating them turns out to be pretty tricky but the very few clues that are there, and which can be correlated with independent information11, seem to put him in about that era; there's nothing that definitively puts him later. Knight-Jadczyk's book spends a lot of time and effort trying to put constraints on this.

Paul was an interesting guy. As discussed by Timothy Ashworth in Paul's Necessary Sin: The Experience of Liberation, Paul had a pretty sophisticated spiritual cosmology, one that was quite a bit more involved than the 'shut up and obey' theology of the rabbis. I won't go into the details here12, but one interesting nugget is that Ashworth's careful translation of Paul's letters shows that Paul was not talking about having 'faith in Christ' but rather about having the 'faith of Christ' ... a little change with big implications for interpretation.

Paul and Peter seem to have been contemporaries, and judging by Paul's letters, they didn't get along. The book of Acts claims that Paul and Peter reconciled, but this is probably just narrative retconning undertaken well after the fact. Peter's Christianity, the Christianity of the Jerusalem Church, was essentially irredentist Judaism, which had little if anything in common with Paul's teachings. Paul, by contrast, was the apostle to the gentiles. The only thing they shared was recognition of a Messiah, but they seem to have differed as to who that Messiah actually was. As noted above, Mark goes out of his way to portray Peter as an idiot, suggesting Mark was in Paul's camp. Mark's Jesus also says a lot which is quite straightforwardly Pauline in character.

Paul's whole thing seemed to have a lot more to do with inner spiritual work than obedience to rabbinical law, with an understanding that only through cultivation of that inner strength and virtue could truly harmonious communities be established. This harkens back to Caesar's attempted social reforms, which seem to have been motivated by a similar intuition regarding the fractality of the human social experience. It's also notable that Caesar seemed to have a lot of faith, in himself, in his luck, and in his mission: there are innumerable instances in which he pressed on against impossible odds, trusting to his own abilities and to Fortune, and miraculously prevailed. So, more speculation: Paul's 'conversion experience', his vision on the road to Damascus, didn't have anything to do with this Jesus fellow (who was invented out of whole cloth by Mark). Instead, it was a sudden, gestalt appreciation of what Caesar's life meant - he grasped the message that Caesar was trying to communicate through his lived example, and then set about trying to explain this to people as best he could. Since he was a Jew, he interpreted this through a Jewish lens: Caesar wasn't just the Divus Julius, he was the Christos Iesus, the (literal translation) anointed saviour of mankind and the messiah of the Jews.

Mark's Jesus, then, was essentially a composite of two figures: Caesar, the Divus Julius, universal saviour of mankind, whose example pointed the way for humanity, and from whose vita many details of the Jesus story were adapted; and Paul, the teacher, who explained what Caesar had meant by his actions and example13.

I don't necessarily think Mark was trying to trick anyone. His audience, citizens of the Roman empire in the late 1st century A.D., would have been entirely familiar with every aspect of Julius Caesaer's life and character, and would have been fully aware of the cult of Divus Julius. They would have picked up on enough of the nudge-nudge wink-wink references to Caesar's story that are sprinkled through Mark's narrative to make the connection themselves. That's probably the origin of a lot of the linguistic correspondences that Carotta notes: Mark put them in there deliberately. Likewise, assuming that the primary audience were specifically the shell-shocked postbellum population of Judea, they probably would have at least heard of Paul, and would likely have recognized much of what Jesus had to say as being Pauline in character. The composite literary character of Jesus would then have served to form an association in the audience's mind between the heroic, apotheosized Caesar, and the widely-ignored teacher Paul (who, had they listened to him and not Peter's bullying Zealots, would have spared their land the devastation of an exasperated Rome).

The Pauline teachings strongly emphasized inner spiritual work - the Kingdom of God is within you kind of thing. If one had the faith of Christ (again, not faith in Christ) one could sort of merge with the holy spirit. This is a central element of the Christian doctrine of anastasis or resurrection and rebirth to this day. Christians still talk about the miraculous effects on their lives of accepting Jesus into their hearts. Just as Christ died, suffered, and rose again, so do Christians suffer in and die to this world, and are born again. The story of Jesus of Nazareth is essentially an allegorical illustration of the psychospiritual technology open to the faithful Christian.

By associating Paul with Caesar, Mark was illustrating that Pauline doctrine. Caesar hadn't started as divine; he became divine as a result of his actions in this world. Similarly, Paul, through his own actions, was able not only to point the way to the holy spirit but to unite with it. The essence of Paul's teaching was to show others how to walk the same path, without having to be a rich, famous Roman emperor bending the world to his will; with the literary fiction of Jesus of Nazareth, Mark was providing an extended metaphor to drive that point home. "Achieve theopoesis at home with this one weird trick! Peter's rabbis hate him!"

Just as Mark almost certainly wasn't engaging in deliberate deception, it isn't necessarily the case that his gospel was composed as a cynically political act. To the contrary, it's likely he was an earnest Pauline Christian, and wrote the document all on his own. Where the Flavians probably come in is simply that they read it, thought hey, we can use this, and exerted their influence to give the book a boost in circulation while encouraging (or at least not discouraging, which comes to the same thing given the savage repression of the Zealots) Pauline Christian churches.

Mark's gospel, which is also to say the Flavian attempt at deradicalization, more or less worked, too. At least at first. Quite a few Jews abandoned Judaism and converted to Christianity; or, given the context of the age, it may be more accurate to say they converted from one form of Christianity (which recognized Judas of Galilee as the Messiah) to another (the Caesar-Paul fusion of Jesus as Messiah). I've often found it interesting that the descendants of those who didn't convert seem to nurse a grudge against Christianity to this day, seeing it as a false religion that wrecked their people by dissolving the religious cement of their societal solidarity. You can't really blame them, as they've got a point on both counts.

Unfortunately for Christianity, over the years many of the new converts - primarily drawn from the Judean population - tried their best to turn the religion back into something more strongly resembling Judaism. Old habits die hard. Thus, for instance, you get the later gospels, which introduce more Judaic elements into the Jesus narrative, and try to rehabilitate the image of the apostles (except for Judas, who even they had to accept was never going to be anything but the villain of the story, and not even in the cool antihero way ... he was just a trash human being). The later gospels also established all the nonsense about how the Old Testament is actually one long extended prophecy predicting the birth and life of the Saviour, which frankly no straightforward reading of the Old Testament really demonstrates. At all. Even the deity celebrated by Jesus - a creator God of peace, love, and forgiveness - has nothing in common with the narcissistic, jumped up volcano demon worshipped by the Israelites. The gnostic Christians, who seem to have been inspired by Paul 'The Father of All Heresies' of Tarsus, were bitterly opposed to the inclusion of the Old Testament in the Bible, on the grounds that it had nothing at all do with the story of Christ.

So, you had something like a power struggle inside the Church, between gnostics who wanted to preserve its original intent, and Judaizers who wanted to go back to being Jewish. Ultimately the Judaizers won. They succeeded in getting the Torah awkwardly grafted onto the New Testament in order to make the Bible, in excluding the more obviously gnostic of the various gospels on the grounds that they weren't consistent with the other (equally fictitious) gospels (3 of which they'd written), and in editing Paul's letters to make them less obviously opposed to the Judaizing influence. They couldn't get rid of Mark, because it was the book that got the ball rolling and everyone knew it, but they did their best to water it down by re-writing the story in the other, longer, gospels, and then lying that Mark was a derivative later work.

Still, the core mission - separating the Jews from their xenophobic, genocidal faith and incorporating them into the empire by means of a more cosmopolitan, pluralistic religion - had been successful.

The next question is how, or really more precisely why, this mutated version of the imperial cult ended up replacing the OG version.

Again, I think the reason was basically political.

By around the 3rd or 4th century, the Empire was entering a terminally rocky period. There were constant, exhausting wars draining the imperial treasury; the economy was going to pot; the common folk were groaning under increasingly onerous taxation that they got increasingly little for14, and with a succession of increasingly unimpressive degenerates declaring themselves emperor and therefore just as divine as Gaius Julius Caesar the imperial cult itself was looking moth-eaten. The empire needed something with which to stabilize an increasingly restive population.

I'm sure you can see where I'm going with this. When faced with a problem, you solve it with the tools at hand. Christianity had already been used very effectively to pacify the population of Judea, and since then it had spread around the empire a bit as one of several mystery cults (along with Mithraism, the worship of Osiris, and so on). Christianity had been based on the imperial cult in the first place, so it was already fairly compatible with the existing social order. Better, in contrast to the imperial cult - which was ultimately based on veneration of a man who had forced the ruling class to submit through sheer force of will, and whose good works were aimed at tangibly improving the material lives of commoners in this world - Christianity advocated for its adherents to meekly submit to the will of the temporal authorities, to accept their lot in this world, and to expect their reward in the next world, where their saviour reigned. Seen from the point of view of an increasingly unpopular aristocracy trying to hold onto their positions in a decaying imperium, it's a no-brainer.

So, that's pretty much the story as I see it. The true Messiah, the Christos, the Saviour, the Redeemer, was one Gaius Julius Caesar. He made such a deep impression on the world that after his shocking murder he was immediately worshipped as a god. After his death, his official cult was gradually perverted by the sociopaths running the empire until it became an unrecognizable parody of itself, with the core messages twisted beyond recognition - what had started as honouring the memory of a man whose example showed that it was possible to run the bastards out of town and make a society that actually works for everyone, was turned into a tool of social control, first to subjugate a troublesome colony, later to subjugate the entire empire. Meanwhile, the memory of the man himself, which couldn't be erased, was instead dragged through the mud to the point that he is now remembered mainly as a brutal tyrant ... the precise opposite of his true nature. Meanwhile, a mutated version of the imperial cult was combined with Jewish themes and used to pacify the Jewish population by luring them away from more violent forms of fanaticism; later, this new version of the cult was imposed across the empire as a last-ditch attempt to maintain social control.

It wasn't entirely, or frankly speaking even primarily, a net negative. Re-reading the above paragraph I suspect that outraged Christians will be under the impression that I'm deeply hostile to Christianity - which I'm not, at all. At the same time that Christianity was warped by Judaizers and later by the institutional church in alliance with the failing Roman state to become a societal control mechanism, the ineradicable memory of Caesar, as transmitted through Paul's poetic gnosticism and Mark's polemics and parables, was inextricably woven through the religion - the two influences twining about one another like the two snakes of a caduceus locked in deadly enmity. The result was the Church's schizophrenic character: narrow-minded religious bigotry on the one hand, transcendent gnosis on the other; authoritarian demands for submission, alternating with benevolence and charity. By and large I think that it's the Pauline strain that has tended to prevail, and has led to Christianity being a force for the promotion of logos - of love, knowledge, truth, and life - far more often than not.

So, why do we care? Why am I writing about all of this?

Partly it's just because I think it's fascinating. But I also think there's a deeper importance to it all. I'll explain my personal perspective on why this story matters in the next and final chapter.

- That coincidence of initials only works in the Roman alphabet. It doesn't work in Greek, for which the names are Ιούλιος Καίσαρας and Ιησούς Χριστός.

- Fun fact: a thousand monkeys randomly slapping a thousand keyboards would take much, much, much longer than the age of universe to compose Hamlet. We did that as a problem in undergrad thermodynamics. The probability of happening upon Hamlet's 130,000 characters by chance (ignoring capitalization, punctuation, and spaces) is 1 in 26130,000, or 1 in 3 x 10183,946. That's a big number: 1 followed by 183,946 zeroes, for those of you unfamiliar with scientific notation. At a typing speed of 200 characters per minute, it would take the monkey about 650 minutes to type out Hamlet. So each year, the monkey would have about 800 chances to type Hamlet before keeling over dead from exhaustion because typing for a year straight without eating or sleeping means a lot of intravenous coffee or, more likely, weapons-grade methamphetamine, and the adrenal glands can only take so much. Since we've got 1000 monkeys that gives us 800,000 Hamlet attempts per year. In the roughly 13.7 billion years since the Big Bang, those 1000 monkeys would have about 1016 Hamlet attempts, which doesn't even make a dent in the ginormous 3 x 10183,946 number of attempts required before the monkeys get it right. Going in the other temporal direction, the last supermassive black hole will evaporate from Hawking radiation in about 10100 years; presuming that the monkeys keep typing past the end of the stelliferous era, through the degenerate era, and right on through to the dark era (quite a trick as protons have decayed by then), the monkeys would have 8 x 10116 Hamlet attempts ... which still doesn't scratch the surface of that immense edifice of improbability that is 1 in 3 x 10183,946. Point being, those thousand monkeys will not type Hamlet even if they keep at it until the heat death of the universe.

- Carotta bases this on the similar Latin verb, possessus, used for both, and proceeds from there to find an identity between each incident in which Jesus casts out a demon with various famous urban battles fought by Caesar during the Civil War.

- Unless you're doing it as a joke, a la the Church of Bob.

- See: Scientology.

- Depending on the chronology - the Biblical account, in which he was the governor of Judea from 26 to 36 AD, doesn't quite line up with others. Knight-Jadczyk goes through quite a bit of work trying to nail down exactly when Pilate was in Judea. 19 AD is her best guess and she's done a lot more work than I have to arrive at it.

- That isn't a typo. I'll capitalize the pronouns for God, but not for Yahweh.

- Romans and Greeks considered circumcision an abomination. As did all Christians until 20th century America. I agree with the Romans and Greeks, strongly, and forgiving my parents for that was one of the more difficult lessons in being a good Christian I've yet had to undergo.

- Before you ask, no, it isn't possible that Mark Antony actually wrote Mark: Antony was dead over a century before Mark was composed. That's about as likely as this blog being actually telepathically transmitted by Edgar Rice Burrough's Martian pulp hero. Actually, now that I think about it...

- As supposed to the pre-Gospel Christians of the Zealotry era, whose Christos was the aforementioned Judas.

- Which is itself tricky, because you start running into all sorts of chronology questions arising from stratigraphy, carbon dating, the reliability of other accounts (Josephus in particular being the definition of the unreliable narrator), and so on.

- Because honestly it's been a while since I read up on it.

- One does wonder why Caesar never bothered explaining it himself. Aside from trusting Brutus, that was probably his greatest strategic blunder. To be fair, he was generally quite busy, what with the wars all over the known world and all. Perhaps he intended to write down his philosophy and never got around to it. Then again, everything he wrote aside from the Commentaries has been lost, so it's possible he did, and it was suppressed.

- Any of this starting to sound familiar?

Reader Comments

That part doesn't seem true, but they were more interesting or inventive than the Judaizers, though the stoic or spiritualist philosophy sometimes feels like it's missing. All were Platonists, with a heavy emphasis on the distinction between the "unknowable" or highest good and the demiurge (who was only evil for some groups of gnostics), and some more dumb fantastical notions about soul attached to the material realm and spirit which strives for the good. Or is it the other way around? Simonians and Baruchians especially incorporated Greek myth, whether with Helen being the soul to be saved by Christ, or Heracles being a prophet ultimately succumbing to lust.

No point in writing this, but I do wonder about how all this mythos was conceived (divine revelation, schizophrenic revelation, natural amalgamation of Enochian and Mediterranean sects, novelists ahead their times, etc).

I like the essay's observations regarding the religion being a pacifier for the populace, which always seemed a strong argument from atheists, and explains why the empire adopted it. Oddly enough, Manicheans adopted the gospels in the Persian empire a century before, apparently.

What to do with it all. Someone with a better memory could say.

Starting at the beginning:

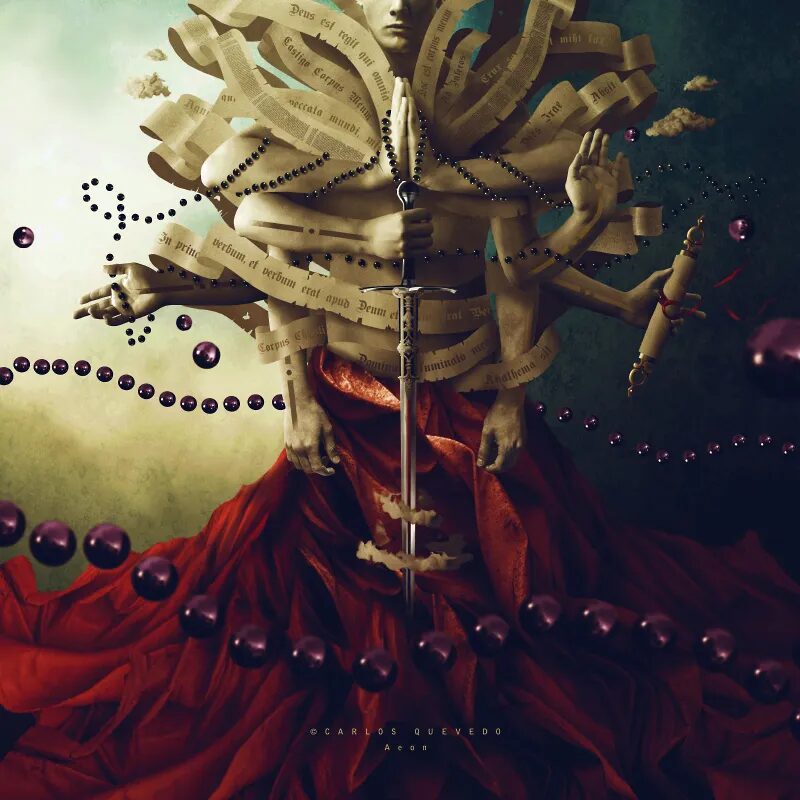

"Exegesis, by Carlos QuevadoIn Chapter 1 of this series, I started with the question of whether Jesus of Nazareth existed, proceeded from. . .

...the assumption that

...the hypothesis that

...show striking similarities to

...might have

...two hypotheses

...I found ultimately unconvincing

...more or less

...this hypothesis

...it's very difficult to see how

...could lead to

...that can be

...that can arise

...might have had

...by whoever

...that can arise

...that might be

...you might gather from

...it seems unlikely

...could

...would tend to

...it rarely happens

...it would have

...more or less

...suggests that

...is generally

...somehow

...I just don't buy it

...I don't think this

...could have

...I think the

...very probably

...is necessarily speculative

...I think there

...a plausible sequence

...can be guessed at

...suggestion was

...it only makes sense that

...would have

...suggests that

...there's a good bet that

...Action Comics Number 1

...it strongly resembles

...seem to

...seems to have

...very probably

...and very probably

...It doesn't seem

...seems to have been

...this may be

...it can be

...It could well be

...the possible

...seems too obvious

...It could be

...isn't necessarily

...reasons to believe that

...was probably

...more or less

...seem to

...seem to

...is probably

...seem to

...seemed to

...seem to

...seemed to

...So, more speculation

...I don't necessarily think

...would have been

...would have been

...would have

...That's probably the

...assuming that

...probably would have

...would likely have

...would then have

...would have

...almost certainly wasn't

...isn't necessarily the

...it's likely

...probably

...more or less

...it may be

...seem to

...seem to have been

...I think the

...pretty much

...I think that

Very powerful stuff. Sign me up!

I can highly recommend Joseph Atwill's Caesar's Messiah. Carter ought to have incorporated more of its premise in his articles, for it is ultimately more insightful than the ideas of Francesco Carotta.

New directives will replace consciousness and the need to be MORAL.

Religion was introduced so as to be the moral path, far from it, a clever divisive tool in which to cause internal and external conflict.

Anyone on the righteous path is on a road to hell and damnation so driven by those sanctimonious types who just love pissing up ones back.

In this article, Carter is stating that the Bibilical Christ is based on the life of Caesar and on the teaching of Paul. It depends on conjecture, that Christianity was established as a political means to control the population. Did Paul speak in parables, miracles, and actions? As Carter notes, it depends on the entire narrative of Christ to be false, from immaculate conception to death on the cross. It depends on the miracles to be myth, changing water into wine, as physically impossible. Carter’s article is thus dependent on his own world view, built from his own experience and education. In my view, the connections are contrived, primarily because it does not speak to the teaching itself.

As noted, Carter depends on Paul teaching in the 1st century AD, so that Paul’s teaching could influence the accepted version of a gospel. It is interesting that the Gospel of Thomas, from the Nag Hamadi library, in one theory is based on the Q source, and some consider the Gospel to be Q. We finally know who Q is? The earliest dating of the Gospel of Thomas is the middle of 1st century AD. The Gospel of Thomas is only parables and saying, no history or action. This Gospel, purportedly of Doubting Thomas the Apostle, refers directly to Jesus. How would Carter’s view of the creation of Christianity explain this?

Many of Jesus’s Biblical teaching could be applied to our current times such is the parable of the sower, which he explains to the disciples so that they understand the meaning of the teaching. The seed is the teaching. The parable of the seed is how the teaching is received by different levels of what Gurdjieff calls Being. He teaches, “narrow is the way”, which means the teaching does not penetrate everyone. He teaches, separate what is of Caesar from what is God, your material desires and goals from your spiritual goals. He teaches, find the pearl in the field, which is the spiritual end, connection to God.

The miracles are just too much for a materialist mindset. As the Gospel of John begins, In the beginning was the Word(logos) and the Word was with God and is God. The energy of the universe, is the result of consciousness or thought, that means consciousness creates the material world. Telepathy, telekinesis, remote viewing, all indicate that consciousness is not limited to our physical understanding of the world. The CIA researches these areas; they are not myth.

From the Gospel of Thomas, Jesus said, "I took my stand in the midst of the world, and in flesh I appeared to them. I found them all drunk, and I did not find any of them thirsty. My soul ached for the children of humanity, because they are blind in their hearts and do not see, for they came into the world empty, and they also seek to depart from the world empty."

jesus, "YESHUA", DID EXIST, AND STILL DOES,, so.. where do we go from here? John Carter, article writer,= not know itc!!

if i give the proof of these recordings, as such in history, Leslie flint, the scole experiment, also this site www.worlditc.org

also "the spirits book", by Allan Kardec, a free pdf for all and sundry, grab it read it, its a beautiful piece of work.. pay attention to page 59, the facimile of the grapevine, i have this tattooed on my chest, as a witness to a resurrection,

so.. whats next John Carter?????????????

your first sentence, did Jesus exist, you say no.. hehe, well, he fukn did, and still does!! fuk religion.. its all power play..

maybe im the only worldly proof of this, but look at "Joshua louis", hope paranormal on youtube, this is very real.. more real than you

looking in the mirror doing a shave, or just praising yourself!! do some proper journo work, it may benefit your career,

so.. whats next??????????????

I have the solid proof, contact josh, ask about me, you will be with a lack of oxygen, also, you will state, "i wanna hear this",

goes to prove your a materialist, no faith, need proof to prove to yourself etc.. sad sorry soul..

il give you your proof, face to face, il show you, play for you my recordings inclusive of a time stamp, and date, oops, same thing..

now, its your move.. or is this check fkn mate!!

spirit, or, those without the physical body, ie, still people, have told me on occasion to stop swearing, of which, i havent.. i wont..

its a language that sorry to say, grabs attention, pple say im angry, im fukn far from that.. im just sad, you celebrate xmas, easter, mums day, dads day, its all a fukn act, following a commercial rule, to feed the media fear porn, to give to the corporates, give them more fukn cash, ie, send mum an dad a card, "love you so much", when in reality they are angry abusive narcistic negative souls, that wished they never had kids..

people should look into things, study things, question things, then, youl be where i am.. the proof, is magic.. awesome..

seeing those, hearing those, understanding those and there surroundings after this physical death, is magic, death is a sleep, to awaken to a solid truth, to be surrounded by those of an alike attract alike, so, if your an arsehole, youl awaken surrounded by arseholes, id say you get my point now,

all the bullshit, ie, covid 19 deception, , the wars, those complicit in all these horrid evil things, i feel so sorry for.. for they too are loved, but they will have to undergo all the sufferings they have caused in every single life form, individual on this planet, and all for the love of the buck, and materialism, they are well and truly fucked.. it is and will be a hell for them, being in the shoes, they said dont fit..

well, presidents, prime ministers, other shit head what ever they are politicians, all are fucked, being complicit in this, nothing can be hidden, from him that put you here, by your own pre birth choice to better yourselves, and by the looks of today, many have fukn failed, and gathered more hellish surroundings for themselves, for when they leave this temporary existence, this earth like pre school of what we really are.. so, from me, knowing this, it so fukn sucks to be you..and im no way angry, hehe, honestly, feel sorry for you and that what is coming your way when you leave this rock, of which, the mighty have raped, abused, polluted, killed for game, and pass the buck.. ffs, nazi maggot fauci, gates, soros, shwabby, and all pms, presidents, etc, complicit in this, get the "spirits book", you can turn this around, if not, hehe, again, it so fukn sucks to be you, related to you, and a fukn offspring of you..

really.. the suffering is coming your way, enjoy your wealth and bollox now, but the time you leave this earth, your well an truly fucked, then your hell, SHALL BEGIN!! again, sucks to be you.. or undo, that you have done, whilst you still have the chance whilst being here in the physical, ffs,, !!

it sucks to be you!!

kind regards..

a friend!!

Only for yourself. And that's the way it should stay.

The author clearly does not accept the scripture that shows judgement comes at the end of the age.