Officials have found traces of a vaccine-derived version of the virus in sewage samples in parts of London and say it is 'likely' transmitting within the community.

Parents are being urged to ensure their children are up to date with their polio vaccinations, particularly after the pandemic when school immunisation schemes were disrupted.

All British children are supposed to have had the first of three polio jabs as a baby, but uptake in London lags behind the rest of the country.

Polio spreads through coughs and sneezes or contact with objects contaminated with faeces, causing permanent paralysis in around one in 100 cases. Children are at a higher risk.

The virus was detected several times between February and May and has continued to mutate, according to the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA).

It is thought someone vaccinated with the live polio vaccine - which uses a weakened version of the virus - abroad travelled to the UK and shed part of the pathogen in their stool.

But health officials insist the risk to the public overall is 'extremely low', with urgent investigations now underway to find anyone who has been infected.

The last time someone caught polio within the UK was in 1984 but there have been dozens of imported cases since then. Britain was declared polio-free in 2003.

The UKHSA said it found 'several closely related' polioviruses in samples collected from the London Beckton Sewage Treatment Works in Newham.

No cases have been confirmed yet but the UKHSA said it is likely there has been some spread between closely linked individuals in North and East London.

It is normal for traces of the virus to be occasionally detected as part of routine testing of sewage, but the findings are normally a one-off.

These normally come from people who were vaccinated with the live oral vaccine overseas and then travelled to the UK. People given the oral vaccine can shed the weakened live virus used in the vaccine in their faeces for several weeks.

Most countries have switched to polio jabs that use inactivated pieces of virus but some developing nations still rely on the live vaccine.

The London samples have caused concern because they were from different people and contained two mutations that suggest the virus is evolving as it spreads between people.

It is unclear how far the virus has spread but it is hoped the outbreak will be contained to a single household or family.

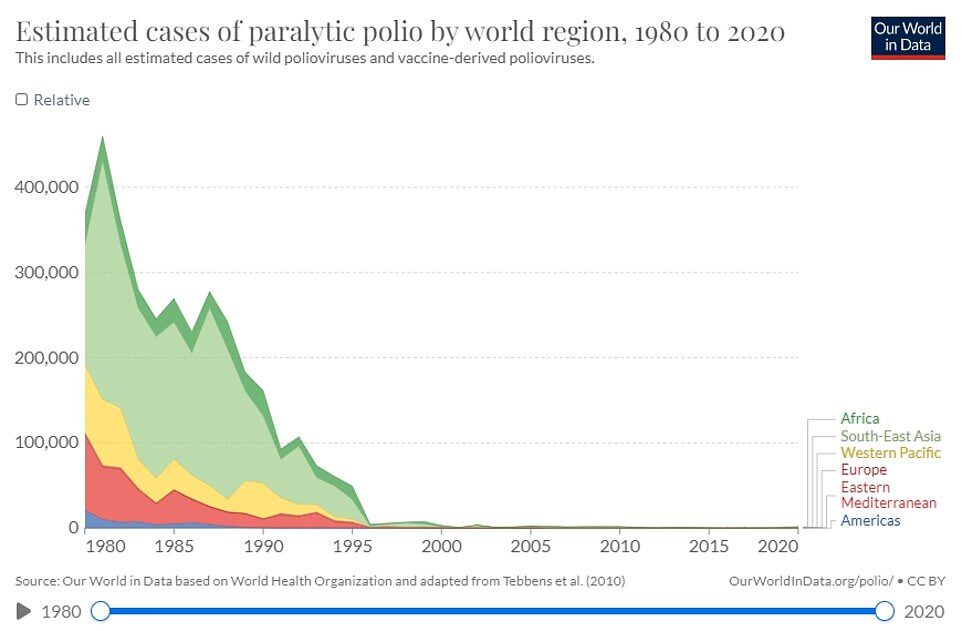

Polio used to paralyse millions of children around the world every year in the 1940s and 1950s and consign thousands to 'iron lungs' — large and expensive machines that helped them breathe.

Most people show no signs of infection at all but about one in 20 people have minor symptoms such as fever, muscle weakness, headache, nausea and vomiting.

Around one in 50 patients develop severe muscle pain and stiffness in the neck and back.

Less than one per cent of polio cases result in paralysis and one in 10 of those result in death.

Dr Vanessa Saliba, a consultant epidemiologist at the UKHSA, said: 'Vaccine-derived poliovirus is rare and the risk to the public overall is extremely low.

'Vaccine-derived poliovirus has the potential to spread, particularly in communities where vaccine uptake is lower.

'On rare occasions it can cause paralysis in people who are not fully vaccinated so if you or your child are not up to date with your polio vaccinations it's important you contact your GP to catch up or if unsure check your red book.

Comment: So even those who have received at least one polio vaccinate can still catch polio?

'Most of the UK population will be protected from vaccination in childhood, but in some communities with low vaccine coverage, individuals may remain at risk.'

The polio vaccine is offered as part of the NHS routine childhood vaccination programme.

It is given at age eight, 12 and 16 weeks as part of the six-in-one vaccine and then again at three years as part of a pre-school booster. The final course is given at age 14.

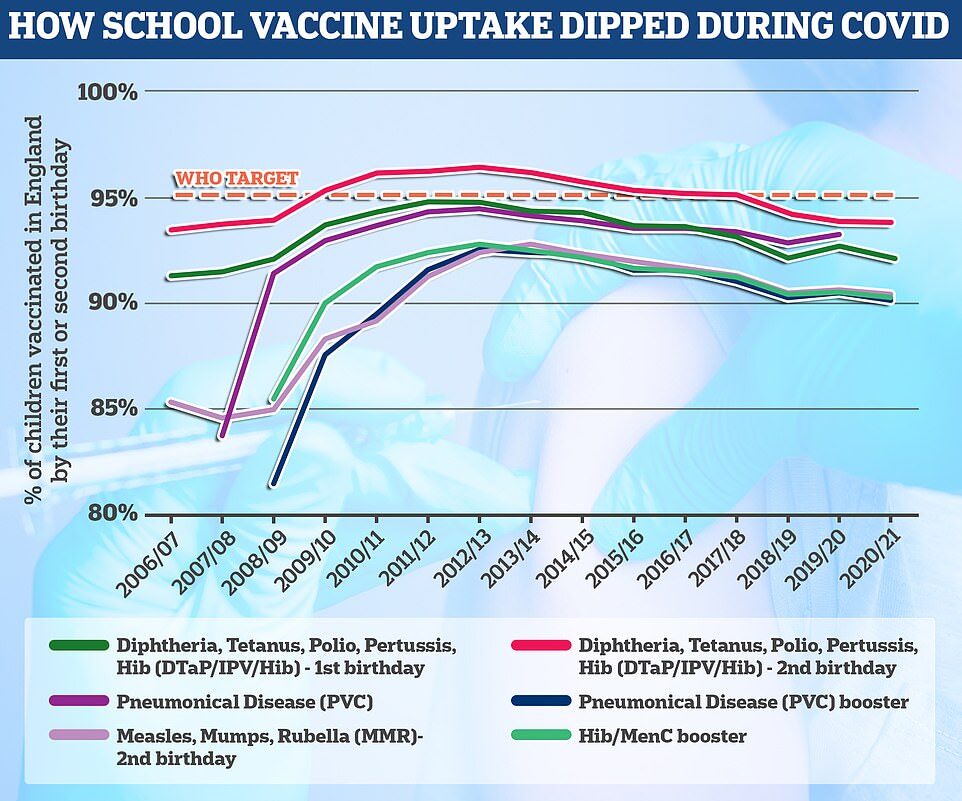

Uptake has fallen slightly nationally during the Covid pandemic but remains above 90 per cent nationally. Rates are lower in London and in poor and ethnic minority communities.

Just 86.7 per cent of one-year-olds in London have had their first dose dose of polio vaccine compared to the UK average of 92.6 per cent.

There are concerns vaccine hesitancy has risen during the Covid crisis due to misinformation spread about jabs for that virus and school closures.

Comment: Understandably; that's what happens when government in league with the sold out media betrays public trust, and there's good reason to believe that people should be equally wary of the polio vaccine that, at least in some countries, has been dogged by its own scandals.

The virus lives in the throat and intestines for up to six weeks, with patients most infectious from seven to 10 days before and after the onset of symptoms.

But it can spread to the spinal cord causing muscle weakness and paralysis.

The virus is more common in infants and young children and occurs under conditions of poor hygiene.

There are three strains of 'wild' polio, which has been largely eradicated throughout Europe, the Americas, Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific.

Types 2 and 3 were eliminated thanks to a global mass vaccine campaign, with the last cases detected in 1999 and 2012 respectively.

The remaining, type 1, wild polio remains endemic in only two countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Cases have fallen from 350,000 in 1988 to just 33 reported cases in 2018, according to the World Health Organization.

There are still occasionally sporadic cases of vaccine-derived polioviruses, however.

These are strains that were initially used in live vaccines but spilled out into the community and evolved to behave more like the wild version.

Vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2), the one that has been detected in London, is the most common type. There were nearly 1,000 cases of VDPV2 globally in 2020.

Since 2019 every country in the world has been using vaccines that contain inactivated versions of the virus that cannot cause infection or illness.

But the UKHSA said countries where the virus is still endemic continue to use the live oral polio vaccine (OPV) in response to flare-ups.

That vaccine brought the wild poliovirus to the brink of eradication and has many benefits.

Comment: The live version has eradicated polio in some countries, and in others its still endemic? Why is the live version effective in some countries but not others? Could sanitation be the other factor?

But in areas with low vaccination rates, the virus present in the jab can spread and acquire rapid mutations that make it as infectious and virulent as the wild type.

Comment: What do they consider a 'low vaccination rate' to be? Could it be that, as with the highly experimental coronavirus jabs, it's the vaccines that are driving mutations?

Professor David Heymann, an infectious disease expert at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said: 'The fact that it has been found in sewage in the UK attests to the strength of the surveillance programmes of UKHSA.

'Its presence in the reminds us that polio eradication has not yet been completed in the world.

'The high vaccination coverage using inactivated polio vaccine in the UK will limit the spread of vaccine derived polio and protect those who have been vaccinated against polio paralysis.'

The UK's drugs watchdog and the World Health Organization are working on a vaccine specifically for vaccine-derived polio strains.

Comment: A vaccine for the vaccine-derived strain? Perhaps improving sanitation would be a better use of the funds.

It is already being used in parts of Africa, including Nigeria, where these types of strains are endemic.

Dr David Elliman, consultant paediatrician at Great Ormond Street Hospital, said the finding strengthened the importance of vaccinating against eradicated diseases.

'Parents sometimes ask why, when diseases are uncommon in UK, or in the case of polio has been eliminated, do we continue to vaccinate against them.

'The answer is that, although we are an island, we are not isolated from the rest of the world, which means diseases could be brought in from abroad.

'The finding of vaccine derived polio virus in sewage proves the point. Although the uptake of polio vaccines is high in UK, there are children who are unimmunised and therefore at risk of developing polio if in contact with this virus.

'The risk is small, but it is easily preventable by the vaccine, which in the UK is killed and so cannot cause the disease.

'There is no upper age limit for the vaccine. Anyone who is not fully vaccinated against polio should seek advice from their health visitor or general practice.'

Here is everything you need to know about the UK polio situation so far:Do vaccines cause polio?

Wasn't polio eradicated?

There are three versions of wild polio - type one, two and three.

Type two was eradicated in 1999 and no cases of type three have been detected since November 2012, when it was spotted in Nigeria. Both of these strains have been certified as globally eradicated.

But type one still circulates in two countries - Pakistan and Afghanistan.

These versions of polio have been almost to extinction because of the polio vaccine. But the global rollout has spawned new types of strains known as vaccine-derived polioviruses.

These are strains that were initially used in live vaccines but spilled out into the community and evolved to behave more like the wild version.

How does it spread?

Similar to Covid, it spreads through coughs and sneezes.

But it can also be spread by poor hygiene if an infected persons' hands have traces of faeces, which contaminates utensils, food and water.

Places with a high population, poor sanitation and high rates of diarrhoea-type illnesses are particularly at risk of seeing polio spread.

How is polio treated?

There is no cure for polio, although vaccines can prevent it.

Treatment can only alleviate its symptoms and lower the risk of long-term problem. Mild cases - which are the majority - often pass with painkillers and rest.

What are polio's symptoms?

Three-quarters of people infected with polio do not have any visible symptoms.

Around one-quarter will have flu-like symptoms, such as a sore throat, fever, tiredness, nausea, a headache and stomach pain. These symptoms usually last up to 10 days then go away on their own.

But up to one in 200 will develop more serious symptoms that can affect the brain and spinal cord. This includes paraesthesia - pins and needles in the leg - and paralysis, which is when a person can't move parts of the body.

This is not usually permanent and movement will slowly come back over the next few weeks or months.

However, even youngsters who appear to fully recover from polio can develop muscle pain, weakness or paralysis as an adult - 15 to 40 years after they were infected.

Although extremely rare, cases of vaccine-derived polio have been reported.

The oral polio vaccine has brought the virus to the brink of extinction and works by providing immunity in the gut, which is where polio replicates.

Comment: There's evidence showing that a new oral polio vaccine being trialled on children in various countries are causing more outbreaks than wild polio: New oral polio vaccine to BYPASS key clinical trials as vaccine caused outbreaks overtake wild polio

The jab, which is different to the version used in the UK, works by using a bit of the virus which can be found in vaccinated peoples' faeces.

The live polio vaccine can then spread between people through contact with faeces, especially in locations with poor sanitation. This can actually improve immunity against polio within a community, as people are exposed to the vaccine.

However, if lots of people are not jabbed and encounter the virus in this way, the virus can mutate until it starts acting like the wild type of the virus, which can cause paralysis.

How did polio end up in the UK?

The polio spotted in Britain was detected in sewage, which is monitored by health chiefs, rather than in a person.

This suggests the virus has been imported from a country where the live polio vaccine is still being used.

Professor Paul Hunter, an infectious disease expert at the University of East Anglia, said: 'Such vaccine derived transmission events are well described and most ultimately fizzle out without causing any harm but that depends on vaccination coverage being improved.'

Could this trigger an outbreak?

Uptake of the polio vaccine is not 100 per cent across the UK and it has dipped further over the last year due to the knock-on effects of the pandemic.

Experts say the best way to prevent the virus from spreading is for Britons to ensure their vaccinations are up to date, especially for children.

Dr Kathleen O'Reilly, an associate professor in statistics for infectious disease and expert in polio eradication, said that all countries are at risk of an outbreak until all polio cases are stopped globally.

This 'highlights the need for polio eradication, and continued global support for such an endeavour', she added.

When was last time Britain saw a case of polio?

The last time someone caught polio within the UK was in 1984 and Britain was declared polio-free in 2003.

But there have been dozens of imported cases since then, which are often detected in sewage surveillance.

However, these have always been one-off findings that were not detected again and occurred when a person vaccinated overseas with the live oral polio vaccine travelled to the UK and 'shed' traces of the virus in their faeces.

Now, UK health officials have detected several closely-related viruses in sewage samples taken between February and May. This finding suggests there has been spread between close contacts in North and East London, where the samples were collected.

Where did polio originate?

Polio epidemics, when the virus is constantly spreading within a community, did not start happening until the late 1800s.

But scientists say that it is an ancient disease that first struck people in Egypt as early as 1570 BC. This is based on depictions of paralysis and weak limbs from that time.

A doctor in London was the first to publish a clear description of polio in infants in a medical textbook in 1789.

Comment: See also: