Patterns deliberately etched onto a bone belonging to a giant deer is further evidence that Neanderthals possessed the capacity for symbolic thought.

Neanderthals decorated themselves with feathers, drew cave paintings, and created jewelry from eagle talons, so it comes as little surprise to learn that Neanderthals also engraved patterns onto bone. The discovery of this 55,000-year-old bone carving, as described in Nature Ecology & Evolution, is further evidence of sophisticated behaviour among Neanderthals.

"Evidence of artistic decorations would suggest production or modification of objects for symbolic reasons beyond mere functionality, adding a new dimension to the complex cognitive capability of Neanderthals," as Silvia Bello, an archaeologist at the Natural History Museum in London, explained in an associated New & Views article.

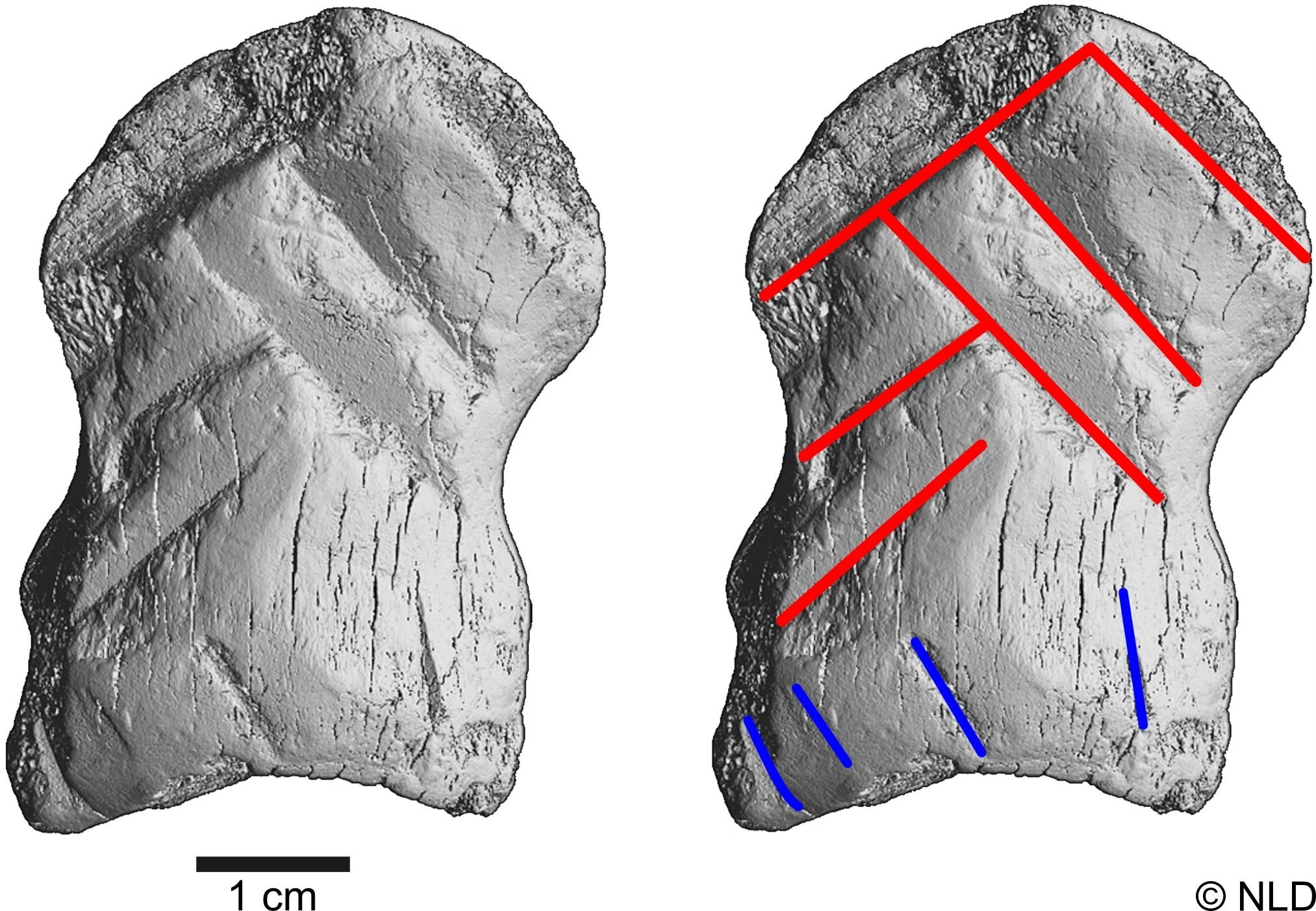

The carving was found at the Einhornhöhle archaeological site in the Harz mountains of northern Germany, and it features a line pattern consisting of six etchings that form five stacked chevrons. The "parallel and regularly spaced engravings have comparable dimensions and were very probably created in a uniform approach suggesting an intentional act," according to the study, led by archaeologist Dirk Leder from the State Service for Cultural Heritage Lower Saxony in Hannover, Germany.

That the bone carving was produced by Neanderthals is not a certainty. Genetic evidence presented earlier this year places the arrival of anatomically modern humans to central Europe at around 45,000 year ago, which post-dates the carving by around 6,000 years. This apparent temporal gap points to the artifact as belonging to Neanderthals, but it's not entirely implausible to suggest that Homo sapiens produced, or possibly influenced, the creation of this artwork.

Bello, who was not involved in the new study, said "we cannot exclude a similarly early exchange of knowledge between modern human and Neanderthal populations, which may have influenced the production of the engraved artefact from Einhornhöhle." This possibility, that Neanderthals learned this skill from modern humans, doesn't diminish their cognitive capacities, however.

"On the contrary, the capacity to learn, integrate innovation into one's own culture and adapt to new technologies and abstract concepts should be recognized as an element of behavioural complexity," wrote Bello. "In this context, the engraved bone from Einhornhöhle brings Neanderthal behaviour even closer to the modern behaviour of Homo sapiens."

Of course, it's also possible that the authors of the new study are completely right — that Neanderthals were indeed responsible for the bone carving, and that modern humans had nothing to do with it. Neanderthals, in addition to their aforementioned cultural contributions, engaged in many other sophisticated behaviors, such as caring for disabled loved ones, burying their dead, and taking care of their teeth. That Neanderthals carved patterns onto bone is thus hardly a stretch.

Reader Comments

yeah, efficient butchering, but if you sucked and were trying to sever a claw for a necklace you might make those marks.

the remains of the paw would've been boiled to clean everything off and consume it. I.e. bone broth.

i been a meat cutter 20+ years. Those marks aren't that amazing. Strikes with a knapped rock would've made those same marks. Trying to hit the same spot would've produced the parallel lines, and you have to come from both sides to sever both tendons.

if they were gonna carve a damn bone on purpose it wouldn't of been a phalanges.

its not like they had carving tools to work on a 2 cm bone. SMFH.

hell don't pay attention to life experience, believe an "expert" who has read books and taken a class, and is TRYING to discover ANYTHING to make a name for themselves.

The rest seems more wishful thinking and conjecture. Doasn't matter as long as the funding keeps flowing ...