Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) climate modeler Dr. Alan Condron and United States Geological Survey (USGS) research geologist Dr. Jenna Hill have found evidence that massive icebergs from roughly 31,000 years ago drifted more than 5000km (> 3,000 miles) along the eastern United States coast from Northeast Canada all the way to southern Florida. These findings were published today in Nature Communications.

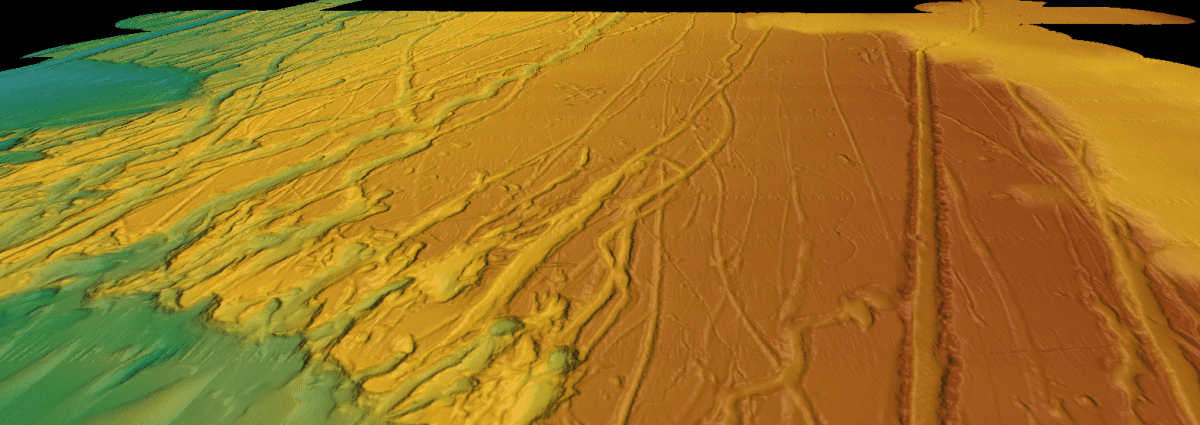

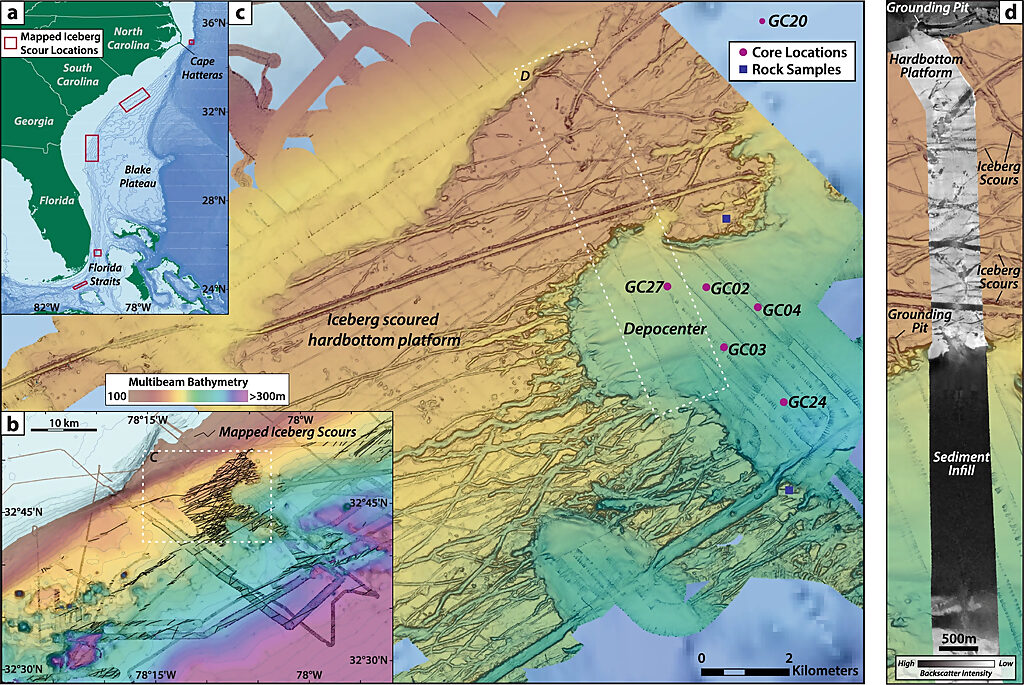

Using high resolution seafloor mapping, radiocarbon dating and a new iceberg model, the team analyzed about 700 iceberg scours ("plow marks" on the seafloor left behind by the bottom parts of icebergs dragging through marine sediment ) from Cape Hatteras, North Carolina to the Florida Keys. The discovery of icebergs in this area opens a door to understanding the interactions between icebergs/glaciers and climate.

"We recovered the marine sediment cores from several of these scours, and their ages align with a known period of massive iceberg discharge known as Heinrich Event 3. We also expect that there are younger and older scours features that stem from other discharge events, given that there are hundreds of scours yet to be sampled," added Hill.

To study how icebergs reached the scour sites, Condron developed a numerical iceberg model that simulates how icebergs drift and melt in the ocean. The model shows that icebergs can only reach the scour sites when massive amounts of glacial meltwater (or glacial outburst floods) are released from Hudson Bay. "These floods create a cold, fast flowing, southward coastal current that carries the icebergs all the way to Florida" says Condron. "The model also produces 'scouring' on the seafloor in the same places as the actual scours"

The ocean water temperatures south of Cape Hatteras are about 20-25°C (68-77°F). According to Condron and Hill, for icebergs to reach the subtropical scour locations in this region, they must have drifted against the normal northward direction of flow -- the opposite direction to the Gulf Stream. This indicates that the transport of icebergs to the south occurs during large-scale, but brief periods of meltwater discharge.

"What our model suggests is that these icebergs get caught up in the currents created by glacial meltwater, and basically surf their way along the coast. When a large glacial lake dam breaks, and releases huge amounts of fresh water into the ocean, there's enough water to create these strong coastal currents that basically move the icebergs in the opposite direction to the Gulf Stream, which is no easy task" Condron said.

While this freshwater is eventually transferred northward by the Gulf Stream, mixing with the surrounding ocean would have caused the meltwater to be considerably saltier by the time it reached the most northern parts of the North Atlantic. Those areas are considered critical for controlling how much heat the ocean transports northward to Europe. If these regions become abundant with freshwater, then the amount of heat transported north by the ocean could significantly weaken, increasing the chance that Europe could get much colder.

The routing of meltwater into the subtropics - a location very far south of these regions - implies that the influence of meltwater on global climate is more complex than previously thought, according to Condron and Hill. Understanding the timing and circulation of meltwater and icebergs through the global oceans during glacial periods is crucial for deciphering how past changes in high-latitude freshwater forcing influenced shifts in climate.

"As we are able to make more detailed computer models, we can actually get more accurate features of how the ocean actually circulates, how the currents move, how they peel off and how they spin around. That actually makes a big difference in terms of how that freshwater is circulated and how it can actually impact climate," Hill added.

Reader Comments

Duh. You are assuming the Gulf Stream was in place the same way it is in modern times...