I found a professor at Harvard connected with the mission, whom I quizzed about its likelihood of success. The man laughed and eventually revealed the team had little idea where Khan was buried. Some colleagues merely dug up a few stories of Khan's death that would be enough to take in a sponsor.

I was blown away. How, I asked, could the archaeologists justify that?

"Son," he laughed. "They're intellectuals. They can justify anything."

People complain about QAnon, but truly lasting, impactful lunacy is always exclusive to intellectuals. Everyone else is constrained. You can't fish on land for long. Same with using a chainsaw for headache relief. An intellectual may freely mistake bullshit for Lincoln logs and spend a lifetime building palaces. Which brings us to Herbert Marcuse.

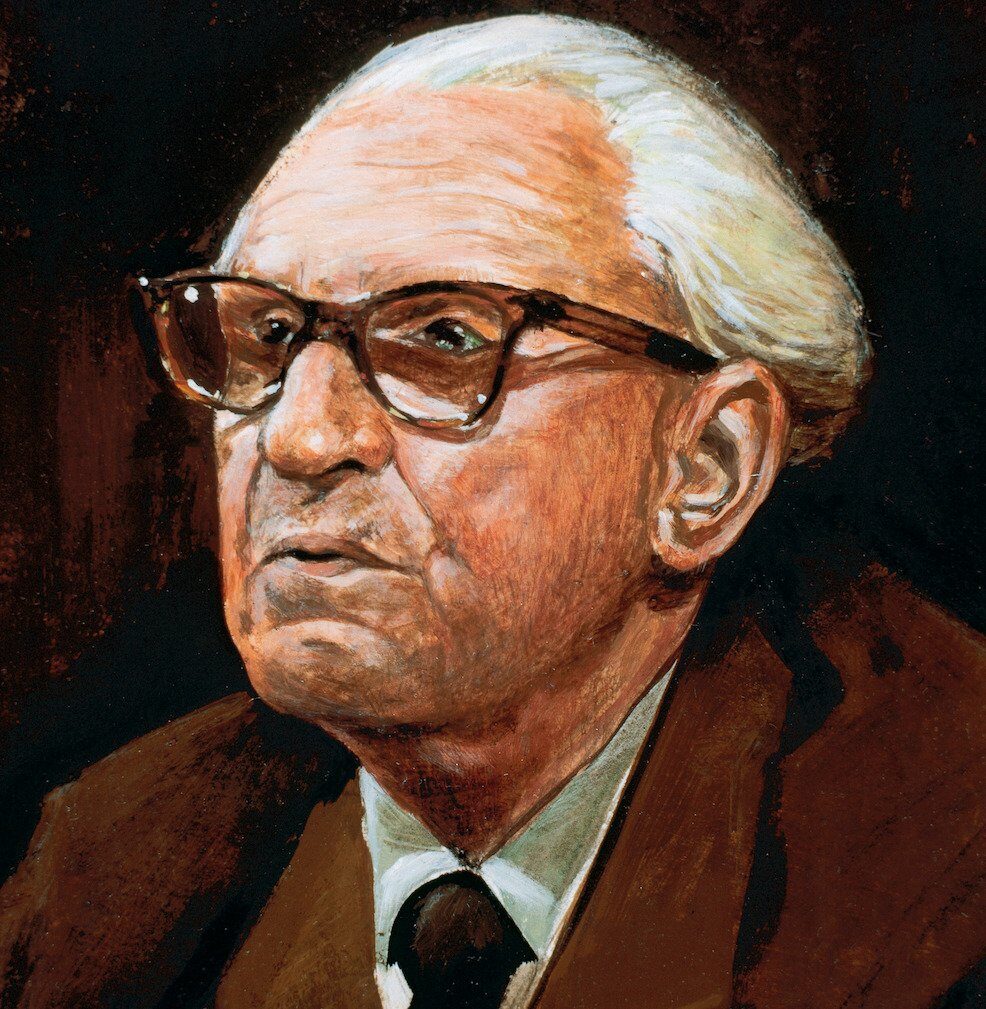

Often called the "Father of the New Left," and the inspiration for a generation of furious thought-policing nitwits of the Robin DiAngelo school, Marcuse was a great intellectual. Most Americans have never heard of him — he died in 1979 — but his ideas today are ubiquitous as Edison's lightbulbs. He gave us everything from "Silence Equals Violence" to "Too Much Democracy" to the "Crisis of Misinformation" to In Defense of Looting to the 1619 Project and Antiracist Baby, and from the grave has cheered countless recent news stories, from the firing of Mandalorian actress Gina Corano to the erasure of raw footage of the Capitol riot from YouTube to...

Marcuse is so influential that subscribers thought it would be a good idea to review his books, rather than go one-by-one through the seemingly interminable list of homage texts dominating bestseller lists in recent years. When I told a friend, he warned with a chuckle about the author's "spectacularly bad synthesis," mimicking the old Reese's Peanut Butter cup jingle: "You got your Marx in my Freud!" I read One-Dimensional Man, and a painful collection essays that included the famed Bible of post-liberal thinking, Repressive Tolerance. Conclusion number one: a person more hostile to the sensual possibilities of literature would be difficult to imagine. Reading Marcuse is like eating a bowl of thumbtacks. The style is nothing, however, next to the ideas. My God, the ideas!

Berlin-born Herbert Marcuse was drafted into the German army in 1916, but didn't see action in World War I. Fortune, obviously concerned with his destiny as the arch-priest of anti-thought in 21st century America, placed him in a rearguard unit. Despite the lack of combat experience, he came out of the war disillusioned, among other things by the experience of watching the German socialist opposition support the war.

After studying at the University of Freiburg, he worked for years at a bookstore, then went back to school, studying under famed philosopher Martin Heidegger. He hoped to help solve the urgent question animating many young intellectuals of his time: what form of Marxism would eventually triumph across the civilized world?

Then, just as Weimar Germany degenerated into exactly the social conditions under which Marx predicted proletarian revolution, German communism flopped, Heidegger became a Nazi University Rector, and a stunned Marcuse soon exiled himself to Switzerland and eventually America, where he would spend the rest of his life trying to come up with an explanation for what happened.

Marcuse's understandable grief and horror over the rise of Nazism, coupled with a humorously powerful loathing for his adopted American home, led him to write the work that first made him famous, 1964's One-Dimensional Man.

The smash #1 bestseller sold 300,000 copies and detailed Marcuse's long-awaited explanation for a) why the proletariat had not risen in postwar Germany, and b) why there was no sense in waiting for it to do so going forward. He explained: not only was the material condition of the worker in modern capitalism insufficiently brutal to spur him to revolution, but technological advances coupled with expanded freedoms allowed even the lowliest employee to fully integrate into the "one-dimensional society," a consumerist hell of mostly met material needs, "pleasure," "fun," and "socially permissible desirable satisfaction," all of which "weakens the rationality of protest."

In this world where the commonest shlub can "have the fine arts at his fingertips, by just turning a knob on his set," it would be impossible, Marcuse lamented, to produce the kind of class alienation Marx envisioned. What's the point of having the right to dissent, if conditions disincline the citizen to revolution?

Independence of thought, autonomy, and the right to political opposition are being deprived of their basic critical function in a society which seems increasingly capable of satisfying the needs of the individuals through the way in which it is organized. Such a society may justly demand acceptance of its principles and institutions...In the later book, An Essay on Liberation, Marcuse anticipated 21st-century liberal attitudes by concluding that the working-class was an actively regressive social force:

By virtue of its basic position in the production process, by virtue of its numerical weight and the weight of exploitation, the working class is still the historical agent of revolution; by virtue of its sharing the stabilizing needs of the system, it has become a conservative, even counterrevolutionary force.After One-Dimensional Man, Marcuse in the 1965 essay Repressive Tolerance set out to argue that the very "stabilizing" rights and freedoms that facilitated this treacherous class integration were the problem that needed conquering. What resulted might be the most impassioned argument against individual rights ever written. It makes the Directorium Inquisitorum read like Dr. Spock on Parenting.

Repressive Tolerance is a towering monument to the possibilities of nonsense in the academic profession. The essay's 10,000 words, alternately hilarious and breathtaking, are circular thinking and the absence of self-awareness raised to the level of art. We don't often encounter an author capable of denouncing "the tyranny of Orwellian syntax" while arguing in the same breath, literally and without irony, that freedom is slavery.

This is an excerpt from today's subscriber-only post. To read the entire post and get full access to the archives, you can subscribe for $5 a month or $50 a year.

Most influential thinker?