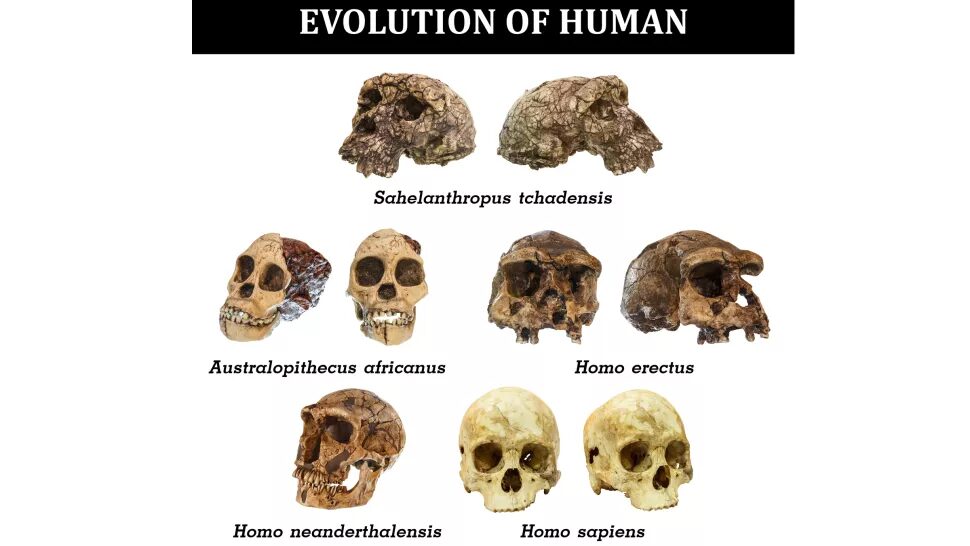

© ShutterstockThe skulls of various human species.

We

Homo sapiens didn't used to be alone. Long ago, there was a lot more human diversity;

Homo sapiens lived alongside an estimated

eight now-extinct species of human about 300,000 years ago. As recently as 15,000 years ago, we were sharing caves with another human species

known as the Denisovans. And fossilized remains indicate an even higher number of early human species once populated Earth before our species came along.

"We have one human species right now, and historically, that's really weird," said Nick Longrich, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom. "Not that far back, we weren't that special, but now we're the only ones left."

So, how many early human species were there?

When it comes to figuring out exactly how many distinct species of humans existed, it gets complicated pretty quickly, especially because researchers keep unearthing new fossils that end up being totally separate and previously unknown species."The number is mounting, and it'll vary depending on whom you talk to," said John Stewart, an evolutionary paleoecologist at Bournemouth University in the United Kingdom. Some researchers argue that the species known as

Homo erectus is in fact made up of several different species, including

Homo georgicus and

Homo ergaster.

"It's all about the definition of a species and the degree to which you accept variation within a species," Stewart told Live Science. "It can become a slightly irritating and pedantic discussion, because everyone wants an answer. But the truth is that it really does depend."

Join us on a journey through human history and explore how evolution and ingenuity shaped us. From the first branches of the Homo family tree to the astonishing achievements our species are capable of today, "The Story of Humans" will reveal how harnessing fire and crafting tools shaped our future, how we triumphed over our Neanderthal relatives, how the invention of agriculture changed history and how the human brain developed.

© Jose A. Bernat Bacete via Getty ImagesAn Australopithecus skull.

The definition of a species used to be nice and simple: If two individuals could produce fertile offspring, they were from the same species. For example, a

horse and a

donkey can mate to produce a mule, but mules can't successfully reproduce with each other. Therefore, horses and donkeys, though biologically similar, are not the same species. In recent decades, however, that simplicity has given way to a more complex scientific debate about how to define a species. Critics of the interbreeding definition point out that not all life reproduces sexually; some plants and

bacteria can reproduce asexually.

Others have argued that we should define species by grouping together organisms with similar anatomical features, but that method has weaknesses as well. There can be significant morphological variation between the sexes and even individuals of the same species in different parts of the world, making it a very subjective way of classifying life.

Some biologists prefer to use

DNA to draw the lines between species, and with advancing technology, they can do so with increasing precision. But we don't have the DNA of every ancient human — the genome of

Homo erectus, for instance, has never been sequenced,

Live Science previously reported.

It gets even murkier when you consider that as much as

2% of the average European's DNA comes from

Neanderthals and up to

6% of the DNA of some Melanesians (Indigenous people from islands directly northeast of Australia in Oceania) comes from Denisovans. So, are we a separate species from these ancestors?

"Some people will tell you that Neanderthals are the same species as us," Stewart said. "They're just a slightly different type of modern humans and the interbreeding is the proof, but again the definition of species has moved on from just interbreeding."

After taking all of this into account, some experts

have argued that the concept of a species doesn't actually exist. But others say that, while a cast-iron definition of a species is almost impossible to achieve, it's still worth the effort so that we can talk about

evolution — including the evolution of our own species — in a meaningful way.

So we muddle on, knowing that a species means different things to different people — which means, of course, that people will disagree on how many species of human have ever existed. It's also a question of what constitutes a human. To answer this question, it helps to understand the word hominin, a large group that includes humans and chimps going back to their shared ancestor.

"The

chimpanzee and us have evolved from a common ancestor," Stewart said. If we decide that humans are everything that arrived after our split from ancient chimpanzees about 6 million to 7 million years ago, then it's likely to be a diverse group. The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History has

listed at least 21 human species that are recognized by most scientists. Granted, it's not a totally complete list; the Denisovans, for instance, are missing.

Those on the list include

Homo sapiens, Neanderthals, the

Indonesian hobbit-size people,

Homo erectus and

Homo naledi. The list also includes other species that existed closer in time to the common ancestor of humans and chimps, and so look more like chimpanzees than modern-day humans. Despite their looks, these species are still known as early humans. "You can't go back 5 million years and expect them to look like us," Stewart said.

If the Smithsonian says there are 21, then you can be sure the diversity is much greater, Stewart said. That's because the list errs on the side of caution, picking the species that are close to universally recognized. For instance, the recently discovered dwarf human species

Homo luzonensis, who is known from just a few bones from a cave in the Philippines, is not included on the Smithsonian's list.

Researchers also suspect there are many other fossilized species yet to be excavated. "The list has only ever grown and I don't see why that will change," Stewart said.

Reader Comments

[Link]

R.C.

Over a a million years early?

Nothing is as it seems.

Michael Cremo rocks

That is all...

I think, looking at the first picture gives us a clue. The homo sapiens skulls are the only one's which are ... white !

They had White Privileges, and used it ruthlessly to wipe out their lesser human brothers. Not even the tiny homo floresiensis could hide ...

I am shocked. Well, not that shocked ... [Link]

And we still won't be if Klaus Schwab triumphs.

Two Great Years from now they will be unearthing cyborg skulls and wondering HTF human evolved into THAT .