When astronauts return to the moon or travel to Mars, how will they shield themselves against high levels of cosmic radiation? A recent experiment aboard the International Space Station suggests a surprising solution: a radiation-eating fungus, which could be used as a self-replicating shield against gamma radiation in space.

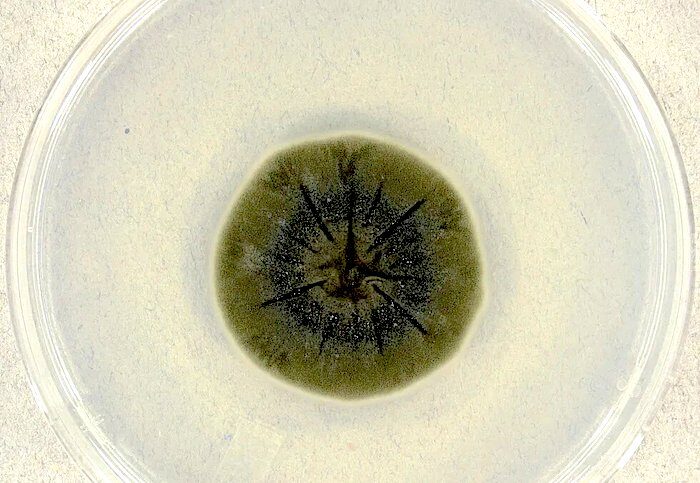

The fungus is called Cladosporium sphaerospermum, an extremophile species that thrives in high-radiation areas like the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. For C. sphaerospermum, radiation isn't a threat — it's food. That's because the fungus is able to convert gamma radiation into chemical energy through a process called radiosynthesis. (Think of it like photosynthesis, but swap out sunlight for radiation.)

The radiotrophic fungus performs radiosynthesis by using melanin — the same pigment that gives color to our skin, hair and eyes — to convert X- and gamma rays into chemical energy. Scientists don't fully understand this process yet. But the study notes that it's "believed that large amounts of melanin in the cell walls of these fungi mediate electron-transfer and thus allow for a net energy gain."

Additionally, the fungus is self-replicating, meaning astronauts would potentially be able to "grow" new radiation shielding on deep-space missions, instead of having to rely on a costly and complicated interplanetary supply chain.

Still, the researchers weren't sure whether C. sphaerospermum would survive on the space station. Nils J.H. Averesch, a co-author of the study published on the preprint server bioRxiv, told SYFY WIRE:

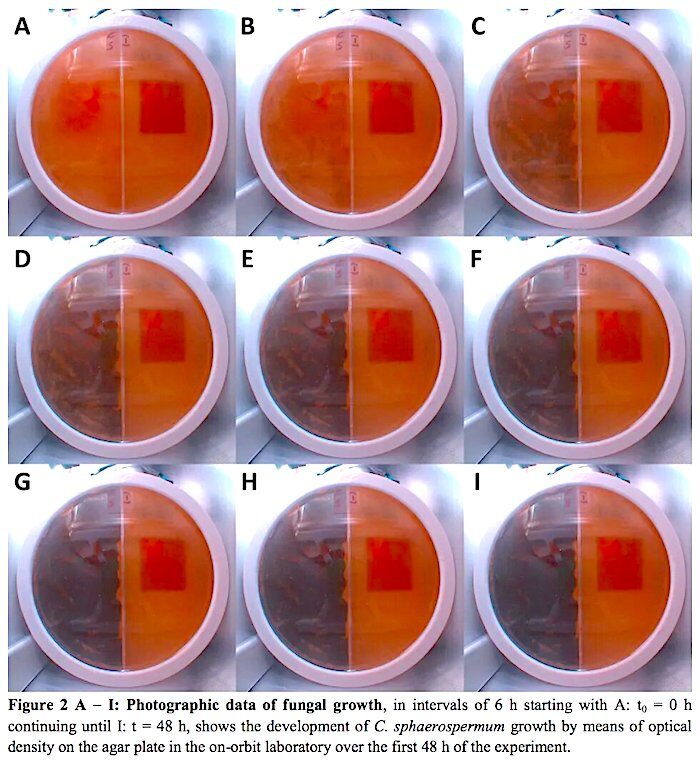

"While on Earth, most sources of radiation are gamma- and/or X-rays; radiation in space and on Mars (also known as GCR or galactic cosmic radiation) is of a completely different kind and involves highly energetic particles, mostly protons. This radiation is even more destructive than X- and gamma-rays, so not even survival of the fungus on the ISS was a given."To test the "radio-resistance" of C. sphaerospermum in space, petri dishes containing a .06-inch layer of the fungus were exposed to cosmic radiation aboard the ISS. Dishes containing no fungus were exposed, too. The results showed that the fungus cut radiation levels by about 2 percent.

Extrapolating these results, the researchers estimated that a roughly 8-inch layer of C. sphaerospermum "could largely negate the annual dose-equivalent of the radiation environment on the surface of Mars." That would be a significant benefit to astronauts. After all, an astronaut who is one year into a Mars mission would have been exposed to roughly 66 times more radiation than the average person on Earth.

To be sure, the researchers said more research is needed, and that C. sphaerospermum would likely be used in combination with other radiation-shielding technology aboard spacecraft. But the findings highlight how relatively simple biotechnologies may offer outsized benefits on upcoming space missions.

"Often nature has already developed blindly obvious yet surprisingly effective solutions to engineering and design problems faced as humankind evolves - C. sphaerospermum and melanin could thus prove to be invaluable in providing adequate protection of explorers on future missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond," the researchers wrote.

Hmm.

R.C.