There are three questions that currently need answering when it comes to the Covid debate: firstly, are we experiencing a second wave? Secondly, is the NHS under imminent threat either regionally or nationally from a rise in infections? And thirdly, will government restrictions actually help?

But the misunderstanding and unrepresentative use of admittedly complex data and statistics is rampant, and we are no closer to getting answers to these questions.

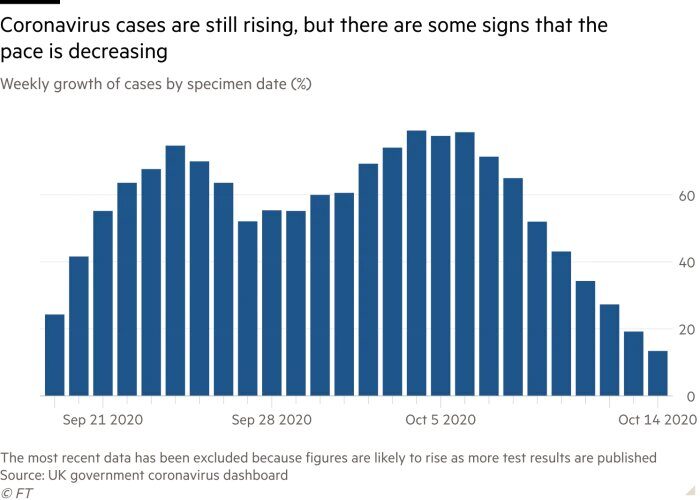

When it comes to the existence of a second wave, it is clear that positive case numbers are up. But there is next to no point comparing positive figures on a daily basis, because of delays in reporting, differences in numbers tested each day, and because of the biases introduced by the Test and Trace system - which by definition directs testing towards those most likely to return positive tests.

Any rise in cases may now be levelling off. The obvious main drivers for the increase were probably secondary school transmission and the return of university students. This is now reaching an equilibrium following initial outbreaks.

Professor Van-Tam in his Downing Street briefing this week stated that the rise in under-30s seems to be declining (as it always would once students achieved herd immunity within their communities) but infections are now penetrating into older age groups. Clearly this is more significant as - unlike in the young - this group are more in danger of being admitted to hospital with serious infection.

But is it true? Well, yes and no. Infections in older groups are rising but when one looks at trends for respiratory infections and hospital admissions over 'normal' years, this is always the case in winter. At the moment, the rise in cases among older age groups bears little or no relation to the spread of the virus among the under-30s. It may be there is some link between the two but to claim that unequivocally is a significant scientific stretch.

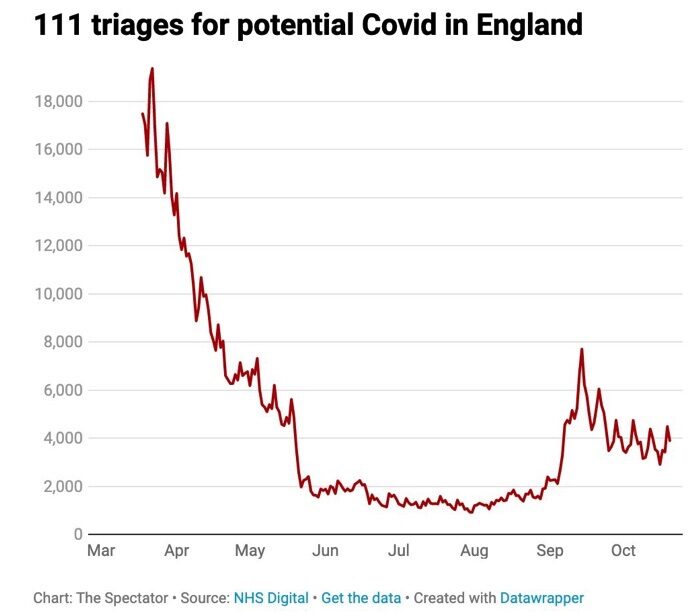

When it comes to hospital admissions, there has been a significant rise in Covid-19 positive patients. But this is not what it seems. Even in the North West it has transpired that critical care bed occupancy was around 85 per cent. This is a lot - but normal for the NHS, which runs a very tight ship when it comes to empty beds and has 'surge' capacity available. Every year, hospital numbers begin to rise in October. And currently figures for bed occupancy are comparable to the average for this time of year.

Overall mortality within hospital has also not significantly increased year on year. If this is a second wave, thankfully it does not seem to be causing any significant increase in hospital admissions or overall death. This is very, very different to the spring of this year.

How then do we then measure what is going on? The daily count of Covid deaths only tells us who has died after testing positive for Covid-19 in the last 28 days. The majority of those who have died of the disease are over 80 and usually have one or more serious underlying health issues.

Given that the number of people dying in hospital is currently in line with the yearly average it may be that coronavirus is not the major factor in many of these deaths. Whichever way one looks at it, respiratory infections of all sorts and admissions to hospital do not seem yet to be overwhelming the health service.

Clearly one must continue to watch the numbers carefully but there does not seem to be much justification yet for a circuit-break lockdown.

Finally, here are some figures which have changed compared to recent years. There has been an increase in excess deaths at home (over a 100 per day, almost all non-Covid related). There have been almost 27 million fewer GP appointments this year. The number of people screened for cancers are down. The number of people treated for heart attacks and stroke has reduced.

A recent NHS survey has revealed that approximately one in six children may have a mental health disorder (from an already troubling one in nine in 2017). When you next hear one of the many professors and scientist promising that the next set of Covid restrictions will save lives, I would suggest this: weigh up in your own mind how many lives have actually been saved, and understand there have been already more than 26,000 extra deaths at home since March - of which Covid-19 accounts for about 3 per cent.

Should we continue further down the road we have taken - or start to question the approach?

About the Author:

Dr Waqar Rashid is a consultant neurologist at St George's University Foundation Hospital NHS Trust, London. This article is a personal view and does not necessarily represent the views of the Trust. He tweets at @DrWaqarRashid1

Reader Comments

Kid: "Wow! You must be old!"

RC

Good one, N!

RC

Of course not. There would have to have been a first wave, as Neizvestno observed. Everything this Spectator article contains about "cases, infections", etc is nonsense.

R.C.