One of the problems with researching and writing about propaganda is that so many people believe it is something alien to democratic states.

What Edward Bernays, considered by many to be a key figure in the development of 20th-century propaganda techniques, said was that "the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society."

Although we usually refer to these techniques by different names today, employing such euphemisms as 'public relations' or 'strategic communication', it is a fact that techniques of manipulation are part and parcel of contemporary liberal democracies.

Although such persuasion activities can involve consensual techniques, they also frequently include less consensual techniques, involving forms of deception, incentivization and coercion. To what extent have such non-consensual methods of persuasion - that is to say, propaganda - been used with respect to Covid-19?

It has recently come to light that 'behavioural scientists' have been providing advice to the UK government's Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE). UK Column reports that this group, named the 'Scientific Pandemic Influenza group on Behaviour (SPI-B)', was (re)convened on February 13, 2020.

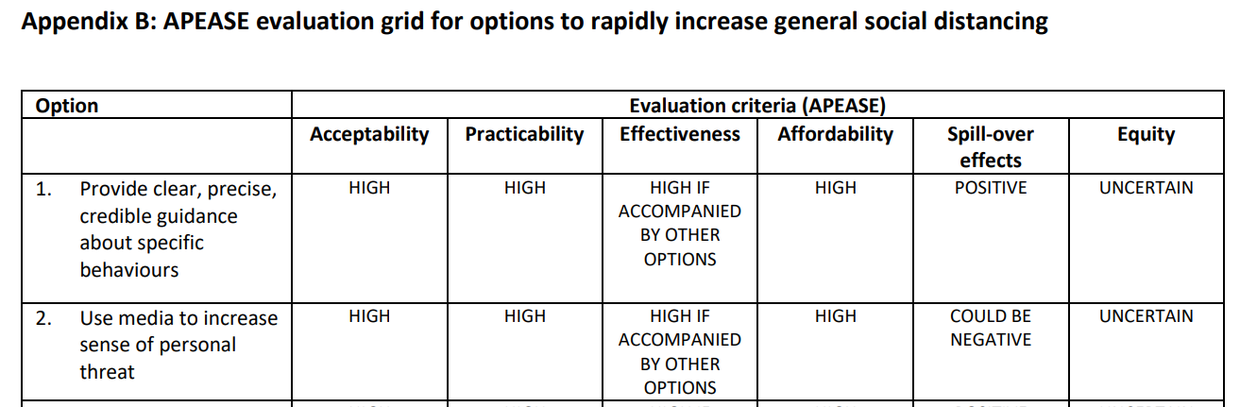

One document produced by this group identifies "options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures," which include persuasion, incentivization and coercion. In the section on persuasion it states that the "perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging." The document also mentions using "media to increase sense of personal threat."

Military involvement

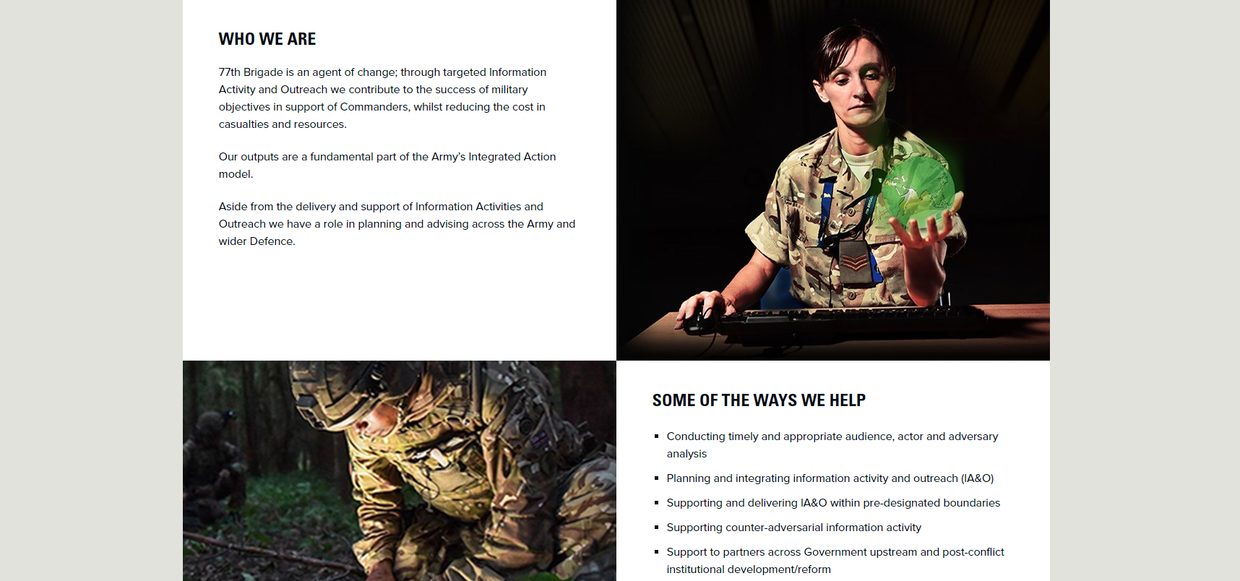

And it has also become public knowledge that the 77th Brigade, part of the British military, has been part of the Covid-19 communication strategy. 77th Brigade activities include information warfare and "supporting counter-adversarial information activity," which includes "creating and disseminating digital and wider media content in support of designated tasks."

Tobias Ellwood, who is both a member of parliament and chair of the House of Commons Defence Select Committee, is, remarkably, a reservist with the 77th Brigade. In an answer to a written question in parliament it was confirmed that "members of the Army's 77th Brigade" are "currently supporting the UK government's Rapid Response Unit in the Cabinet Office and are working to counter dis/information about Covid-19." The Rapid Response Unit itself was established in 2018 in order to, according to its head Fiona Bartosch, counter "misinformation" and "disinformation," and "reclaim a fact-based public debate."

According to the Times, Sir Mark Sedwill backed the creation of the unit, which in turn had developed out of a wider national security review which he himself had led. Sedwill is an extremely powerful individual, holding the posts of cabinet secretary, head of the Civil Service and national security advisor. A recent Guardian article noted that Sedwill is described by some as a "securocrat" and "the most powerful man in the UK."

Online censorship

Meanwhile, tech giants have willingly been signing up to an aggressive strategy of censorship. YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki has declared that it would act to remove anything going "against World Health Organization" recommendations. Notable removals from YouTube include interviews with Dr John Ioannidis of Stanford University and British physician Professor Karol Sikora.

At the same time, the casual deployment of the 'conspiracy theory smear' seems to have become a key part of closing down legitimate questioning. For example, author Douglas Murray has described carefully how a think-tank associated a discussion on the origins of the coronavirus with a far-right 'conspiracy theory', effectively worthy of censorship, even though Western governments have been investigating the possibility that the virus leaked from a laboratory in Wuhan.

Murray insightfully observes, "When the term 'conspiracy theory' is watered-down or made redundant as a term by being used of things that may be true, then we're in trouble. It shuts down interrogation." Columnist Melanie Phillips used the term to smear Lord Sumption's critique of lockdown, even though his argument made no reference to anything that could be construed as suggesting 'conspiracy'.

Behavioural scientists talking about increasing levels of perceived threat, the integration of military 'information warriors' with executive 'rapid response units', direct censorship of scientists expressing doubt regarding policy responses to Covid-19, and liberal use of the 'conspiracy theory' smear provide a potentially toxic combination that threatens to significantly - if not profoundly - distort public sphere discussion in favour of power.

In the case of Covid-19, that means it is very likely the activities described here will have shored up the UK government's narrative, which has promoted lockdown policy and various invasive measures such as social distancing. Indeed, government advisor Professor Robert Dingwall has said the UK government has "effectively terrorized" people "into believing that is a disease that is going to kill you".

Uncertain science

The problem, of course, is that the science regarding Covid-19 is not settled at all. There have been, and continue to be, credible voices expressing serious doubts over the response to Covid-19, whilst UK Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty has made clear that for the population as a whole the risk of death is "low," and that even in the most high-risk group "the majority of people who actually get this infection do not die." Whitty also made clear that for most people contracting the virus, the result is symptom-free, or only a mild or moderate disease that does not require hospitalization.

On Friday 22 May, Professor Sunetra Gupta of the University of Oxford started to question the effectiveness of lockdown and warned of its dangers. "The truth is that lockdown is a luxury, and it's a luxury that the middle classes are enjoying and higher income countries are enjoying at the expense of the poor, the vulnerable and less developed countries. It's a very serious crisis," she said. And this week it has been reported that Norwegian health chief Camilla Stoltenberg is saying that, following an analysis of the latest data, lockdown was not necessary to deal with the virus.

It is a reasonable assumption that those involved in employing tools of manipulation and propaganda would defend their activities on the basis that the science was confirming Covid-19 was a uniquely threatening virus and that, in order to achieve a greater good, vast and intrusive interventions along with a manipulative 'persuasion' operation were necessary.

If, however, it transpires that the lockdown responses we have seen have either been unnecessary, or worse have actually created a greater level of suffering and harm than would otherwise have been the case, then there will be many people with hard questions to answer.

That will certainly be the case for those scientists whose modelling was used to justify the initial lockdown strategy. But it will also be the case for those behavioural scientists advising the government to increase people's sense of fear, the military staff involved with manipulating the public sphere, and those tech giants who have willingly censored scientists and other critical voices.

And as we move inevitably into a period of reckoning, all of us would do well to remember that both democracies and science depend, fundamentally, upon freedom of expression and the free circulation of ideas. Without a robust defence of these, democracy and science are both moribund.

Dr Piers Robinson, who researches and writes about propaganda and communications. He is the author of The CNN Effect: The Myth of News, Foreign Policy and Intervention and Pockets of resistance: British news media, war and theory in the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Follow him on Twitter @PiersRobinson1

- Bad scientific opinion used to justify lockdown instead of good scientific opinion to prove lockdown utterly unnecessary.

- No good health advice e.g. regarding boosting immune system.

- NO economic opinion to provide a cost-benefit analysis of lockdown vs. no lockdown.

Proof that the news is just state propaganda.

Ministry of Truth!