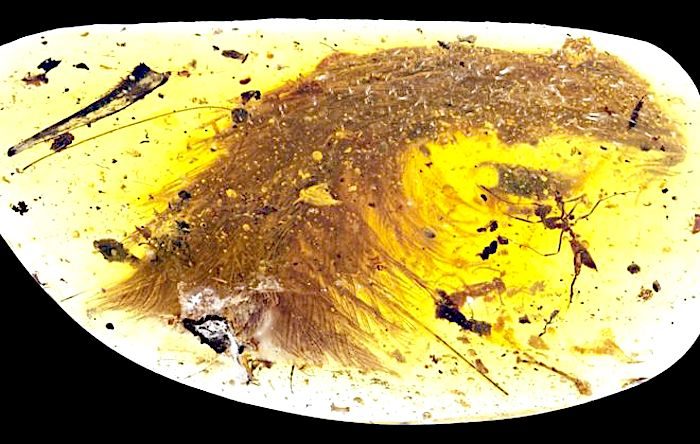

© Current BiologyFeathered tail preserved in amber from North-Eastern Myanmar

The tail of a feathered dinosaur has been found perfectly preserved in amber from Myanmar. The one-of-a-kind discovery helps put flesh on the bones of these extinct creatures, opening a new window on the biology of a group that dominated Earth for more than 160 million years.

Examination of the specimen suggests the tail was chestnut brown on top and white on its underside. The tail is described

in the journal Current Biology.

"This is the first time we've found dinosaur material preserved in amber," co-author Ryan McKellar, of the Royal Saskatchewan Museum in Canada, told the BBC News website.

The study's first author, Lida Xing from the China University of Geosciences in Beijing, discovered the remarkable fossil at an amber market in Myitkina, Myanmar.

The 99-million-year-old amber had already been polished for jewelry and the seller had thought it was plant material. On closer inspection, however, it turned out to be the tail of a feathered dinosaur about the size of a sparrow.

Lida Xing was able to establish where it had come from by tracking down the amber miner who had originally dug out the specimen.

Dr McKellar said examination of the tail's anatomy showed it definitely belonged to a

feathered dinosaur and not an ancient bird.

© Cheung Chung-TatArtist's impression: Dinosaur was about the size of a sparrow

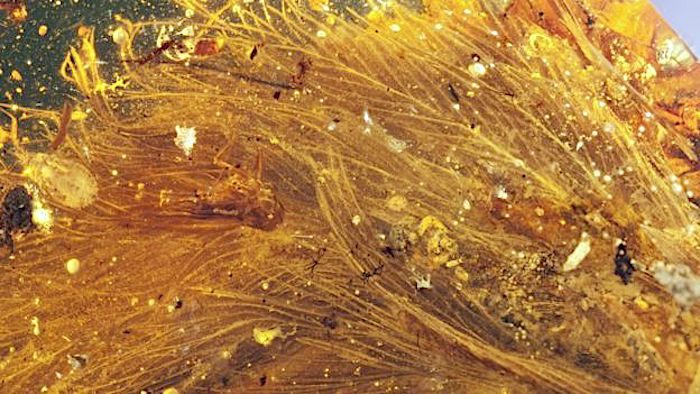

© Current BiologyDinosaur plumage preserved in exquisite detail

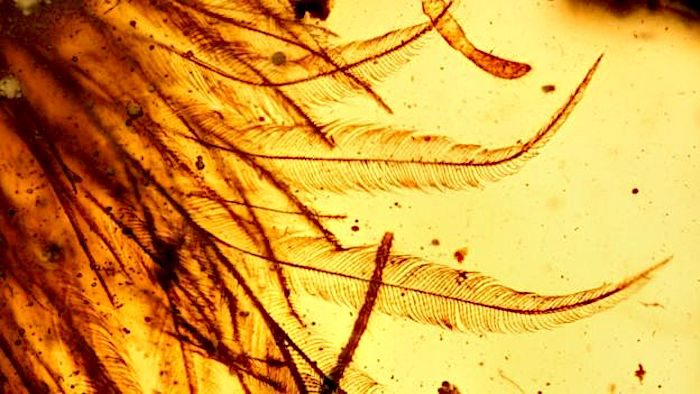

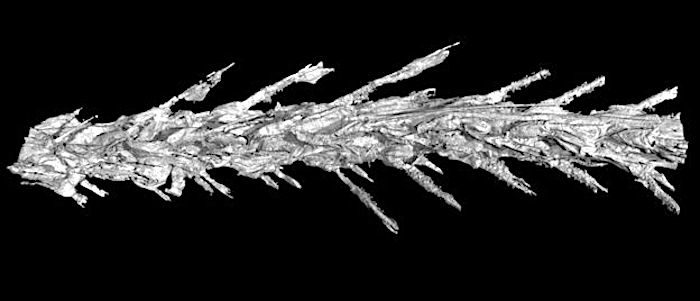

© Current BiologyMicroscopic barbules on tailfeathers

"We can be sure of the source because the vertebrae are not fused into a rod or pygostyle as in modern birds and their closest relatives," he explained.

"Instead, the tail is long and flexible, with keels of feathers running down each side."Dr McKellar said there are signs the dinosaur still contained fluids when it was incorporated into the tree resin that eventually formed the amber. This indicates that it could even have become trapped in the sticky substance while it was still alive.

Co-author Prof Mike Benton, from the University of Bristol, added: "It's amazing to see all the details of a dinosaur tail - the bones, flesh, skin, and feathers - and to imagine how this little fellow got his tail caught in the resin, and then presumably died because he could not wrestle free."

Examination of the chemistry of the tail where it was exposed at the surface of the amber even shows up traces of ferrous iron, a relic of the blood that was once in the sample.

The findings also shed light on how feathers were arranged on these dinosaurs, because 3D features are often lost due to the compression that occurs when corpses become fossils in sedimentary rocks.

The feathers lack the well-developed central shaft - a rachis - known from modern birds. Their structure suggests that the two finest tiers of branching in modern feathers, known as barbs and barbules, arose before the rachis formed.

© Current BiologyThe feathered tail was originally thought to be the remains of plant matter

© Current BiologyThe small dinosaur might have been alive when trapped in amber

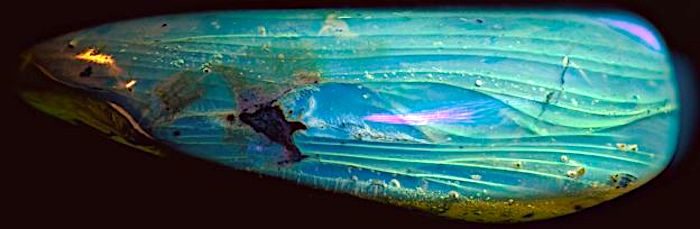

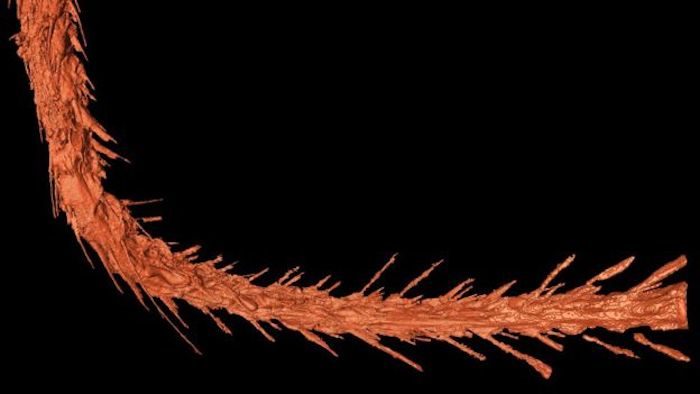

© Current BiologyThis CT scan reveals how feathers were inserted along the tail

Kachin State, in north-eastern Myanmar, where the specimen was found, has been producing amber for 2,000 years. But because of the large quantity of insects preserved in the deposits, over the last 20 years it has become a focus for scientists who study ancient arthropods.

"The larger amber pieces often get broken up in the mining process. By the time we see them they have often been turned into things like jewelry. We never know how much of the specimen has been missed," said Dr McKellar. "If you had a complete specimen, for example, you could look at how feathers were arranged across the whole body. Or you could look at other soft tissue features that don't usually get preserved."

Other preserved parts of a feathered dinosaur might also reveal whether it was a flying or gliding animal."There have been other, anecdotal reports of similar specimens coming from the region. But if they disappear into private collections, then they're lost to science," Dr McKellar explained.

Dr Paul Barrett, from London's Natural History Museum, called the specimen a "beautiful fossil", describing it as a "really rare occurrence of vertebrate material in amber".

He told BBC News:

"Feathers have been recovered in amber before, so that aspect isn't new, but what this new specimen shows is the 3D arrangement of feathers in a Mesozoic dinosaur/bird for the first time, as almost all of the other feathered dinosaur fossils and Mesozoic bird skeletons that we have are flattened and 2D only, which has obscured some important features of their anatomy.

"The new amber specimen confirms ideas from developmental biologists about the order in which some of the detailed features of modern feathers, such as barbs and barbules (the little hooks that hold the barbs together so that the feather can form a nice neat vane), would have appeared also."Earlier this year, scientists also

described ancient bird wings that had been discovered in amber from the same area of Myanmar.

I bet the seller is kicking himself in the ass. He'll take it out on subsequent buyers.

R.C.