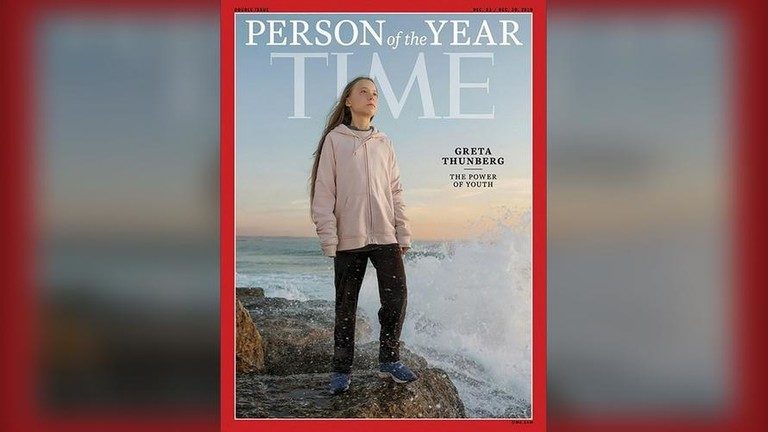

Edward Felsenthal, the editor-in-chief of TIME boasted that 16-year-old Greta Thunberg is the magazine's youngest choice to be named Person of the Year.

I was not the least bit surprised - by now it would have been an upset if the headline-making environmentalist failed to reap yet another publicity reward - but still alarmed.

Gone are the days when TIME chose adult men, like Martin Luther King or Winston Churchill as the magazine's person of the year (Adolf Hitler too - the award is for the most influential, not necessarily the most virtuous public figure).

These days the accent is on youth, and Greta Thunberg personifies the much acclaimed 'wisdom of the child'. That is why three Norwegian MPs nominated Thunberg for the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.

The transformation of a teen schoolgirl into the global conscience for climate change is driven by the imperative of reversing the relationship between adults and children.

Throughout the Western world the authority of adulthood is in crisis. Adulthood is increasingly associated with negative attributes and grown ups feel less and less able to provide guidance to young people. The flip side of the erosion of adult authority is the tendency to look to young people for solutions and answers. That is why Western society's depreciation of adulthood coexists with adulation of the supposed wisdom of children.

Arguably the most grotesque manifestation of this trend is the spectacle of politicians and dignitaries intently listening to Greta at high profile international meetings. A thunderous standing ovation is guaranteed by the mere appearance of this symbol of an infantilised political culture.

In making her TIME magazine's Person of the Year or offering her a platform at a meeting of world leaders, children are in effect invited to condemn the older generation. And Greta has been more than ready to rise to the occasion. The theme of adult irresponsibility has been her most common refrain - appearing in her lecture to the United Nations climate change summit as far back as a year ago, and in every major speech she has made this year.

"Since our leaders are behaving like children, we will have to take the responsibility they should have taken long ago," she said last December. "We have to understand what the older generation has dealt to us, what mess they have created that we have to clean up and live with."

Green demonstrators have readily embraced the narrative of adult guilt. Posters declaring, 'You'll Die of Old Age, We'll Die of Climate Change' or 'I Am Ditching School Because You Are Ditching Our Future' point the finger of blame at slothful adults who are supposedly responsible for the imminent early deaths of their offspring. Recently, a placard screaming 'Adults Ruin Everything. Stop Brexit' at an anti-Brexit demonstration indicated that the spirit of adult blaming is not confined to the problem of planetary destruction.

Encouraging children to revolt against their irresponsible elders is the inevitable outcome of adult-blaming. That is why the head of politics at Cambridge University could call for children as young as six to be given the vote. Professor David Runciman advocated this proposal on the grounds that young people were "massively outnumbered" by the elderly and that this created a democratic crisis that had to be put right.

You know that society is in deep trouble when six-year-olds are assigned the responsibility for determining society's future - but this is not just about battle lines being drawn up according to generational divides.

Greta and other unspoilt youth idols provide cover for the anything-but-innocent elites, who can hide that they lack the courage of their convictions, or the ability to get others to follow them behind the fiery rhetoric of youth.

Who needs grown ups to lead the nation when children are ready to put right the mistakes created by old people? But that might not be quite the optimistic sentiment it is presented as.

By Professor Frank Furedi, a sociologist and author. His book How Fear Works: The Culture Of Fear In the 21st Century is published by Bloomsbury

Comment: Trump pointed out the absurdity of TIME's cover choice: