Who exactly is going on strike?

According to The Connection, the strike is expected to start at 10pm on Wednesday, December 4, when workers at SNCF (France's national rail company) and RATP (Paris' regional transport authority) officially walk out. Air France air and ground crews will be on strike, making flights in and out of French airports difficult, notably because air traffic controllers will also walk out. Public travel generally will be made even more difficult by today's announcement by lorry drivers that they intend to blockade major French roads from December 7 onwards. French people, reliant on cars to get to work have started stocking up on cans of petrol to have as a fall back in case garages run dry due to issues with delivery.

Postal workers and other public service staff are expected to protest-three teaching unions have given the Ministry of Education formal notice of their intention to strike. The police intend to hold action in support of the strikes from 10am to 3pm across all police services and won't take part in additional airport or motorway checks throughout the day.

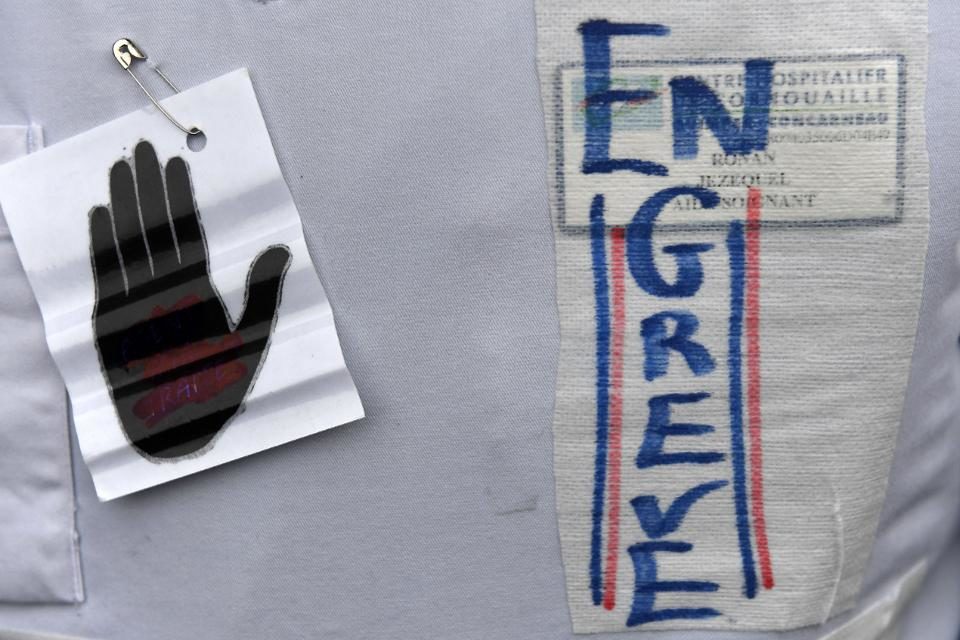

Ambulance drivers and hospital workers - who were on strike last week -will likely join the fray and recent striking firefighters might be added to the mix. The strike also has the support of the Gilets Jaunes movement, which has taken to the streets every weekend for the past year. One barristers union is also in favour, calling December 5, "a day for dead justice".

The strike is against the French government's proposed pension reforms. President Macron wishes to streamline the current pension system comprising 42 separate regimes into a single operating system. The new system would introduce a "points system" of retirement, which threatens the current early retirement age of many public service workers.

More importantly for the protesters, the reforms would impact how much money they receive. Currently, public sector workers' pensions are calculated on the salary they earned for the last six months of working life - which is usually the highest for most people - and they are also assessed on the 25 best years of their working life. The new system will take every year into account, meaning that people who worked on lower salaries for years or had periods of unemployment, will see that translate into a lower pension.

The first smaller strike on September 13 was dubbed "Black Friday" and brought Parisian streets to a standstill, with some tailbacks trailing as far as 200km (125 miles). However, people generally seem to believe this will be much, much bigger. Firstly, in size, as it includes all union members across the major sectors comprising public life. Secondly, the five large trade unions in the RATP (Paris transport network) have called for "unlimited strikes" and want this to be only the first, so it's likely to continue. Many unions have warned that strikes might run until Christmas. Thirdly, because of the stakes. French workers have been fighting the government against pension reforms since 1995 when Jacques Chirac tried to change the system; the proposed reform at that time, according to The Local, brought people to the streets in a way that hadn't been seen since the spring of discontent in May 1968. After weeks of protest at the government threatening to increase the age of retirement, the plan was dropped. The new plans are much more severe.

Comment: Discontent with government cut backs is not limited to France, many countries within the EU, and elsewhere, are seeing a similar collapse in the overall quality of life; the difference in France seems to be that its citizens are taking the risk to push back.

It would appear that while Macron's government did manage to smear and suppress the Gilet Jaunes movement to some extent, that hasn't quelled the overall feeling that the lives of citizens are being sacrificed for government ideology:

- Watch French riot police knock down elderly woman... during rally for 80 year old who died after being hit in the face by tear gas grenade

- Irate French farmers descend on Paris in 1,000-strong tractor convoy to protest EU regulations

- What do the protesters in France want? Check out the 'official' Yellow Vest manifesto

- Economists forecast trouble: Rising food prices globally mean it's more and more expensive to eat

Also check out SOTT radio's: NewsReal #26: Globalization vs Nationalism - The Hidden Causes of The Yellow Vest Protests in France