He's dialing up the charm offensive over the two days he gives Forbes unprecedented access to the normally hidden, clandestine spy-tech industry, estimated to be worth $12 billion and rising. It's the first time Dilian has gone on camera, openly discussing the more controversial aspects of the industry, namely its ethics. This is, after all, a market that's been linked to snooping on murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, not to mention attacks on human rights lawyers and activists in London, Mexico, the U.A.E. and beyond.

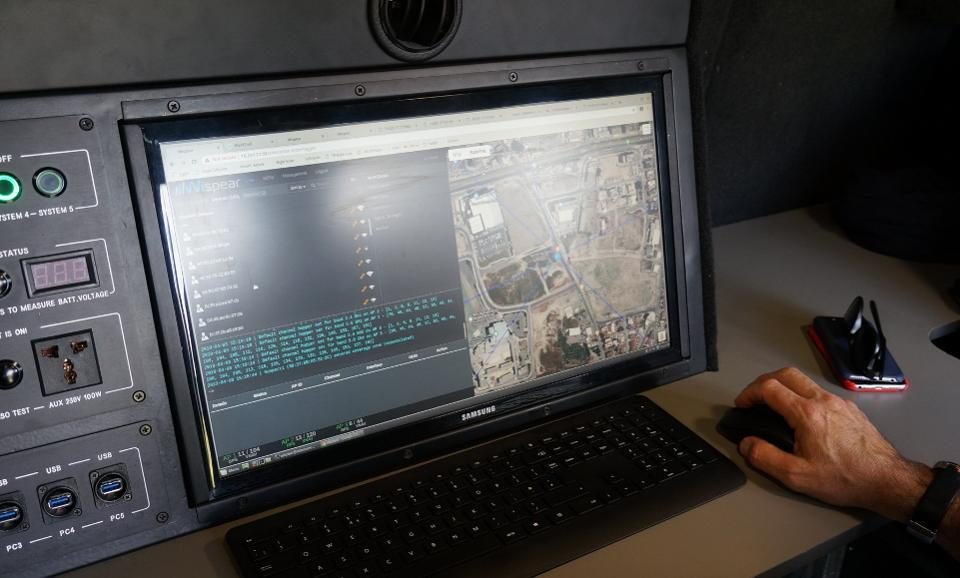

But first he wants to show off the power of his surveillance kit. His van, which costs between $3.5 million and $9 million, depending on how much spy tech the customer desires, is the A-Team truck spliced with a Bond car. To show what it can do, Dilian has posted a colleague 200 yards away. "We will trace them, we will intercept them and we will infect them," Dilian says, as if delivering a line from Ocean's 11. He forces the mock target's Huawei phone to connect to his Wi-Fi hub, and from there he hacks into the device, silently installing surveillance software. No clicks required from the victim. Inside the vehicle, seconds after they're sent, WhatsApp messages from the device appear on a monitor in front of Dilian.

Anyone who believes their WhatsApp chats, or any parts of their digital lives, are 100% private would be quickly disabused of that idea after spending two days with Dilian, even if you have to take the spyware salesman's claims with a pinch of salt. His van offers a cornucopia of spyware tools that Dilian is offering as part of his new enterprise: Intellexa. It's a one-stop-shop, cyber arsenal for cops in the field. Alongside Android hacking tools, there's tech that can recognize your face wherever you travel, listen in on your calls, and locate all the phones in an entire country within minutes, Dilian boasts. Every 15 minutes, he can know where you are, he says.

He claims such tools are designed to snoop on terrorists, drug cartels and the world's most egregious criminals. But that's not always the case. Politicians, human rights activists and journalists have been targeted too. Most infamously, associates of Khashoggi and other Saudi Arabian activists were allegedly targeted by stealth iPhone spyware called Pegasus in the lead-up to his torture and slaughter in Istanbul. The mythically themed malware was coded by NSO Group, a company Dilian is closely associated with: His first surveillance business, Circles, merged with NSO in 2014, when U.S. private equity firm took control of both for a total of $250 million. NSO has since strenuously denied having anything to do with Khashoggi's death.

Then, a little over a month after Forbes spent two days with Dilian in an eerily quiet Cyprus this spring, there was an attempt to hack the WhatsApp and iPhone of a U.K.-based human rights lawyer who was working on cases that sought to have NSO's Israel export license revoked. Again, NSO was blamed. The company says it's investigating.

Human rights activists contend that companies like NSO aren't doing enough to curb abuse of their products. "If you think about how much data your phone and your devices have on you and think about how powerful these technologies are ... this should be hugely concerning," says Edin Omanovic, a surveillance researcher at Privacy International. "Every single company has a responsibility to protect human rights no matter where they are in the world, no matter what kind of business they run."

Dilian brushes off the criticism. Don't blame the dealers, blame the customers, he argues. "We are not the policemen of the world, and we are not the judges of the world," he adds, suggesting that it's down to governments to ensure that export controls and other safeguards are adequate to prevent use against the civil rights and journalist communities. "It's hypocritical to come and say, 'How come you sold to Mexico?' It's legitimate. Why not? If the U.S. approves sales to Mexico, the E.U.," Dilian says. "We work with the good guys. And sometimes the good guys don't behave."

Besides, Dilian notes, in most cases it's not even possible for surveillance companies to keep tabs on the use of their systems. "Most of the products that are sold in this industry you cannot monitor. And more than that, customers don't want you to know who are their suspects."

A transparent business?

Back in the comfort of his offices in downtown Larnaca, a 30-minute flight from his homeland and a useful place to quickly ship his NSA-level spy tech to EU-based governments, the Intellexa chief is talking up a new age of openness in the spyware industry. That he gave Forbes such unprecedented access to his business over two days is a sign of a notable shift from the taciturn, wary approach previously maintained by the market's millionaire leaders. Just last month, his former partner Shalev Hulio, CEO of NSO Group, gave interviews to Israeli media and 60 Minutes. "We are here. We will build beautiful systems that will work for the benefit of the good guys and the universe. And we need to say it, and I don't think we need to hide it," says Dilian. Dilian is also reticent about the provenance of his customers, though he lets slip a few clues. He describes a demo of Wi-Fi interception in Indonesia, where he also has an office. He talks of customers in Africa, the Persian Gulf and the Far East. A colleague talks of discussions with Mexicans chasing cartels. Dilian later confirms to Forbes that Circles sold its tech — which could track any phone in six seconds with just its number — to Mexico, a country where a spyware scandal erupted after lawyers for the families of 43 missing students were targeted, allegedly by NSO malware, in 2016. Dilian denied knowledge of an alleged $3.5 million sale to the U.A.E., evidence of which was provided in the legal challenge to NSO and Circles in Israel.

That deal has brought controversy after the plaintiffs released what they claimed was an email interaction between Dilian's former Circles cofounder Eric Banoun and Ahmad Ali Al Hibsi, from the National Council for National Security in the U.A.E. The plaintiffs claimed it showed discussions about spying on phones belonging to the Emir of Qatar and the prime minister of Lebanon. It's unclear whether Banoun agreed, but plaintiffs said Circles "took this opportunity without any hesitation and tried to deliver the evidence by hacking phones numbers that were sent to them." (Banoun didn't respond to requests for comment. Neither Circles nor NSO Group provided a response.)

Dilian admits he's had to curb some of his own sales tactics. Some years ago, in a bid to sell Circles' cell tracking kit to an unnamed country "somewhere south of America," a potential customer provided him with two numbers to trace. He was told by the police chief for the nation that they belonged to two bandits. Believing him, Dilian recalls going ahead with the work and later being told that once the police had located the two phones, they sent 3,000 officers to raid the village where the suspects were hiding out. "We were young," he offers as an excuse. "Today I would say no."

The private life of a spy-tech dealer

If the surveillance world needed a spokesperson to defend its besmirched reputation, it could do worse than spy turned entrepreneur Dilian. Eloquent and mirthful, a grin somewhere between charming and impish often written across his stubbled face, Dilian opened up to Forbes about his private life — ironic, given his trade. The son of artists, he recalls his boyhood in Jerusalem as "heaven" with "Jews and Arabs, religious and nonreligious all together in one peaceful city." His long life in intelligence started at just 18. He spent 24 years in the Israel Defense Forces, first in an elite combat unit, where he learned the value of in-field surveillance tools that would become his stock-in-trade. Later he was made chief commander in the technological unit of the IDF's Intelligence Corps.

After coming out of the clandestine world, Dilian tried his hand as a consumer tech entrepreneur, though his first two attempts foundered. One enterprise was Vidyo. It was much the same as Google's Chromecast, "but ten years before and without their knowledge of how to get really to the market." He remembers being on Fifth Avenue in New York City, proudly looking at his product in a store. "And then a year later I closed it with a nice loss of half a million dollars."

Next came an abortive attempt to get an engineering firm, SolarEdge, off the ground, but then he struck gold with Circles. After over a decade away from the spy-tech world, Dilian joined two partners — Banoun and Boaz Goldman — in 2010 to set up what was, at the time, a revolutionary surveillance technology. With a single phone number, the company could locate a smartphone. With more options on the market, the cost of this form of tracking has decreased. But at its peak, Circles made $120 million in sales in a year, one source with knowledge of the company says.

In 2014, Circles sold for just under $130 million to American private equity firm Francisco Partners, which had already acquired 90% of NSO Group for $120 million. The two merged, creating a powerful cellphone surveillance company called Q Cyber Technologies. As part of the deal, the six owners of Circles split the money equally, leaving Dilian with $21.5 million.

Dilian again took a short hiatus from the spy world to become executive vice president at $1 billion-valued 3D-printing giant Stratasys. When he left two years later, he says, he sold his shares and made himself another $2 million. In two short years, he'd gone from failed entrepreneur to multimillionaire. He plans to make a lot more with Intellexa, believing he can turn it into a $100 million revenue a year proposition before the end of 2020. In a few years, he's thinking $300 million to $500 million, built on the back of the five separate companies that form the "alliance." They include the company responsible for the WhatsApp surveillance Dilian showcased from the van: Android spyware maker Cytrox, a little-known Macedonian start-up Dilian rescued from the abyss with a sub-$5 million acquisition. There's also the French 3G and 4G hacking specialist Nexa Technologies.

He's expecting money to pour in as governments struggle to break the security being built up by the likes of Apple, Google, Facebook and its WhatsApp business, and turn to his industry. Dilian says the "bad guys" are the first to adopt such encrypted comms technologies. He calls for the right balance to be found, where citizens are given privacy but the apps can still be spied on, appearing to put him on the side of the FBI; the agency has been calling for back doors into those apps in recent years. At the moment, that balance doesn't exist, he believes.

Comment: An oxymoron, if ever there was one. How can any citizen enjoy privacy if even one of their apps can be hacked?

And then, with that mischievous smile, adds: "We make a lot of money from the imbalance."

Neither Dilian's charm nor his boasts about profits will win over digital rights activists. And despite his claims on expected revenue, even Israeli investors who were once involved in or intrigued by the market now balk at the idea of funding tech used by repressive regimes. One former investor in NSO Group, who was bought out when Francisco Partners made the $130 million swoop, told Forbes he would probably never dip into the industry again because of "moral issues." "The same goes for gambling and porn," he added, providing a novel comparison to the so-called "lawful intercept" market.

One Israeli investor based in San Francisco says that over the years he's had as many as 20 pitches from Israeli surveillance companies. "We would typically just kill it off after the first interaction," he says. "Most venture capitalists will not invest in these type of companies. ... We know that the tools can easily get into the wrong hands and be used against people that we do not want to target." VCs are also after businesses who will exit but the pool of potential acquirers in the interception game, is very small, he adds.

A fine example of how drastically investment in the spyware game can backfire can be found in the case of another Israeli company, Ability Inc. Ability sold similar location tracking technology as Circles; both exploited a part of telecommunications infrastructure known as SS7. It tried to break the U.S. market by going public on the Nasdaq. But over the last two years, it's come off the rails, reporting millions in losses and falling revenues over recent months as it has failed to gain business and was thrown off the Nasdaq for failing to maintain a minimum bid price of $1.00 per share. It reached a new nadir last month, when Ability and its founders were charged by the SEC with defrauding investors by lying about the contracts they had signed.

Incredibly, it appears that the infamous drug baron Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán inadvertently had a part in Ability's demise. In order to get investors on board in 2015, the SEC said, Ability lied about its backlog of orders, one of which the company claimed was from its largest customer, a Latin American police agency, that would have resulted in $104 million in sales. It turned out that Ability had no written agreement with that agency and the oral deals they had made were with management "who had been terminated as a result of the then-recent prison escape of a notorious international narcotics trafficker." Forbes later confirmed with a source who has knowledge of Ability's business that the agency was Mexican and the dealer was El Chapo, whose escape from the maximum security Altiplano jail in 2015 resulted in high-ranking prison officials being charged.

Anatoly Hurgin, Ability's CEO, didn't respond to questions on his Mexican business.

Copycat surveillance

With a lack of VC interest at home, the industry is instead finding foreign financiers in the U.S. and U.K. Private equity firms have been throwing money around as they seek cash-generating businesses whose finances and operations they can engineer to churn out as much money as possible before they pass. Earlier this year, NSO's ownership switched hands when the primary backer, U.S.-based Francisco Partners, sold its stake back to the founders and U.K.-based Novalpina Capital.

But Novalpina is now learning how much negative press owning a spyware firm can attract. The company was compelled to issue a lengthy statement following the WhatsApp attack, outlining how it would be reviewing its new portfolio company's ethical practices. Later, Yana Peel, a co-owner of NSO through her stake at Novalpina, which was cofounded by her husband, Stephen, resigned as chief executive of the Serpentine Galleries. She said she was stepping down so the work of the gallery would not be undermined by what she described as a "concerted lobbying campaign against my husband's recent investment." Novalpina declined to make anyone available for an interview.

John Scott-Railton, a researcher at Citizen Lab, a surveillance-industry-tracking organization based at the University of Toronto, said it was still risky business getting into bed with spyware companies, especially where you can't predict abuses. Investors in private equity firms also may not realize what they're getting into, he adds. "Do they understand the reputational risks? I suspect they don't."

Neither the besmirched reputation of the industry nor the dearth of VC funding is deterring the many new spyware businesses cropping up around Tel Aviv. A growing number of NSO and Circles copycats have appeared in the country and are approaching unimpressed financiers. One investor passed along a long list of companies in the market, all with almost-mystical names like Candiru, Quadream, Magen and Merlinx, and all shrouded in mystery, their ethical standards obscure.

Dilian, acting the industry spokesperson in front of a Forbes camera, gives both a final defense of the growing market and another deferral of responsibility: "The universe in a way needs our product. ... Once in a while, some government misuses it, and it shouldn't happen. And the world needs to find a way."

Ummmm... Just a few lines up they said that this intrusive, vile spyware was to be used to spy on terrorists... They can't even finish an article without blowing holes in that bit of fiction? Really? This is just more in your face proof that they want you demoralized and disheartened, convinced that privacy is dead and they control the information sphere. To which I say bullshit! We just need programmers to wake the hell up and start writing stuff that exposes and eliminates their malware tools.