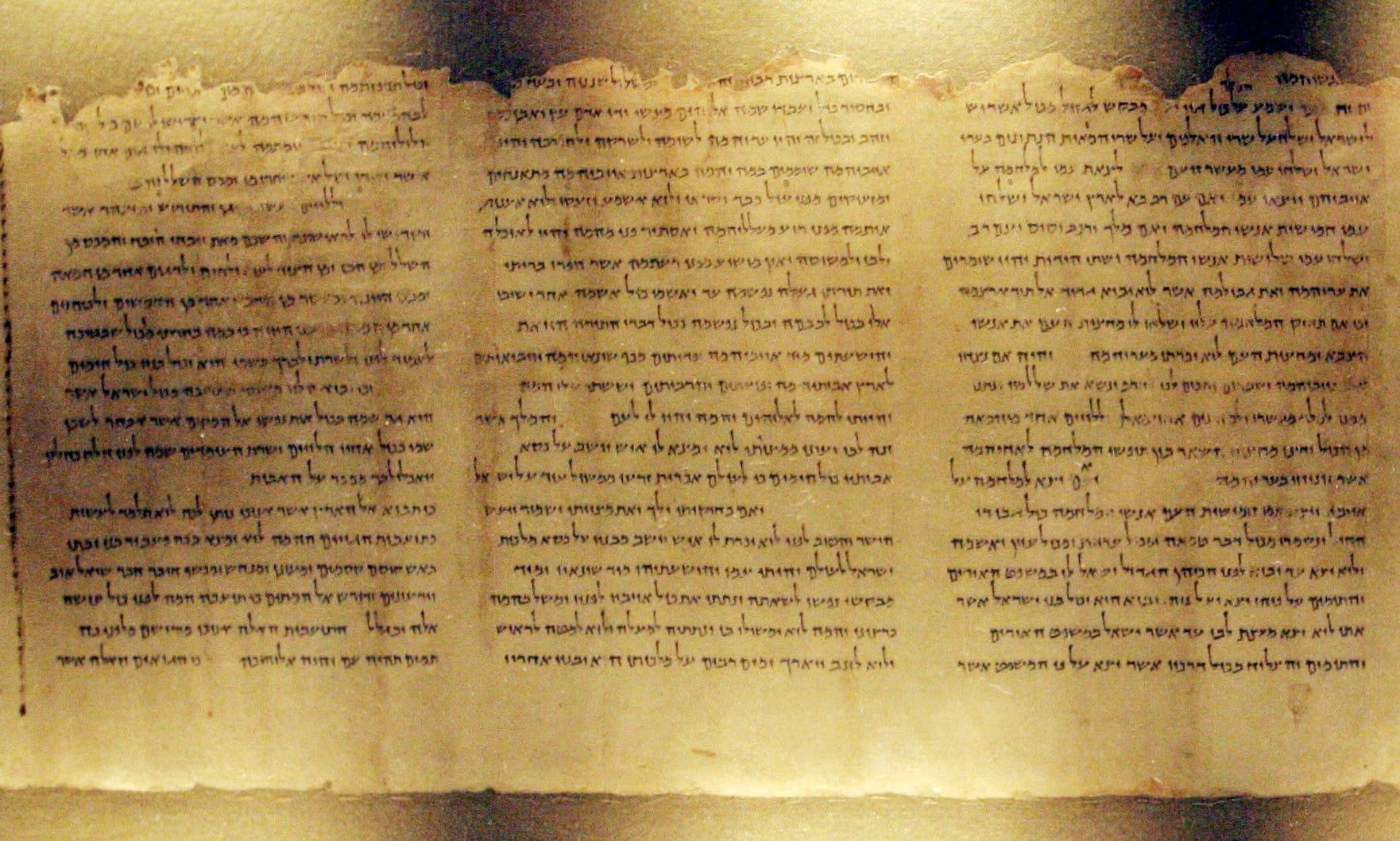

© Michael Kappeler/AFP/Getty ImagesPart of the Temple scroll, one of the Dead Sea scrolls.

The Dead Sea scrolls have given up fresh secrets, with researchers saying they have identified a previously unknown technique used to prepare one of the most remarkable scrolls of the collection.

Scientists say the study poses a puzzle, as

the salts used on the writing layer of the Temple scroll are not common to the Dead Sea region. "This inorganic layer that is really clearly visible on the Temple scroll surprised us and induced us to look more in detail how this scroll was prepared, and it turns out to be quite unique," said Assistant Professor Admir Masic, co-author of the research from Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US.

"These salts are not typical for anything we knew about associated with this period and parchment making," he added.

Found in the middle of the 20th century but dating back to between the third century BC and the first century AD,

the Dead Sea scrolls are made up of copies of writings that form parts of the Hebrew Bible, hymns and writings about religious texts and practices. Some sections are mere fragments while others are intact scrolls. The discovery of the ancient texts itself sounds like something out of scripture: nomadic Bedouin shepherds found cloth-wrapped scrolls hidden in jars in the Qumran caves of the West Bank.Most of the writings are on parchment sheets - some of which have been tanned, an eastern practice, while some are untanned or lightly tanned, a western practice.

One of the most remarkable intact scrolls is the Temple scroll, a manuscript that was reportedly sold by the Bedouins to an antique dealer who wrapped it in cellophane and stuck it in a shoe-box under his floor. The scroll is now housed with many of the other Dead Sea scrolls in the Shrine of the Book, part of the Israel Museum in Jerusalem.

The bright, pale scroll - which is more than 8 metres long and written on parchment sheets whitened through treatment with a salt called alum - has a number of unusual features. It is wafer thin - experts have suggested it might have been made from an animal skin split in two - and

unlike most scrolls, the text is on the flesh side of the skin. Even more surprisingly, the text is written on a thick mineral-containing layer that forms a writing surface on top of the collagen."The layer reminds [one] of plaster on a wall," said Prof Ira Rabin, another author of the study.

Now, writing in the journal

Science Advances, Masic and colleagues report that they have analysed a fragment of the Temple Scroll to unpick the makeup of this mineral-containing layer.

The results suggest the writing surface is largely composed of sulfate salts, including glauberite, gypsum and thenardite - minerals that dissolve in water and are left behind when the water evaporates.

However, the researchers say these salts are not typical for the Dead Sea region,

raising questions of where exactly they came from.Prof Timothy Lim from the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the study, said the findings did not show that the Temple scroll did not come from the region, even if the salts used in its preparation might come from elsewhere.

However, Prof Jonathan Ben-Dov from the University of Haifa disagreed: "I am not the least surprised to learn that a part of the scrolls was not prepared in the Dead Sea region. It would be naive to assume that they were all prepared there."

Rabin said: "We believe

the [Temple scroll] primary treatment is consistent with the 'western' way [of parchment preparation]. But the detailed treatment is rather unique."

The team say the findings raise questions of how best to conserve the Dead Sea scrolls, noting that the sulfate salts might mean the scrolls are more sensitive to small changes in humidity than previously thought.

Among those who welcomed the findings was Dr Kipp Davis from the Dead Sea Scrolls Institute at Trinity Western University in Canada, one of the

academics who recently revealed that the trade in fragments of the Dead Sea scrolls was full of fakes."This is an important study that reveals a number of things which promise to continue to be helpful in the study of ancient Jewish scribal culture, but moreover also in our efforts to develop more robust and reliable techniques for evaluating authenticity and forgery in ancient manuscripts," he said.

And on exactly what evidence are these 'salts' accounted for? Got a forensic trail here? Back to when and who handled them since. And on what evidence is the claim for salt mineral profile claimed. Because salt in that region was culled from many sources and commonly circulated. Has a comparative salt analysis been made of the various documents? Why not?

'Western way', 'Eastern way' is pure crapola. Constructs of always corrupt academics without a shred of supporting evidence.

You want to make claims like this you stand in front of cameras and answer the criticism of your toughest critics. No dodging. No hiding behind lecterns. In full view for all to see. In real time. No 'maybe later'.