Dozens of people who grew up near the former National Fireworks Co. site, where toxic chemicals are known to have been dumped, now have brain tumors. But experts say it's harder than it seems to pin the disease on any one environmental factor.

Growing up in West Hanover, Nick Squires and his friends thought little of the countless hours they spent playing in the woods and ponds of a 240-acre property where a fireworks manufacturer and other companies are now known to have dumped toxic chemicals for decades.

It wasn't until years later that Squires says he realized that spending so much time living alongside land once considered a sure-fire candidate for a federal Superfund site may have made him and others sick.

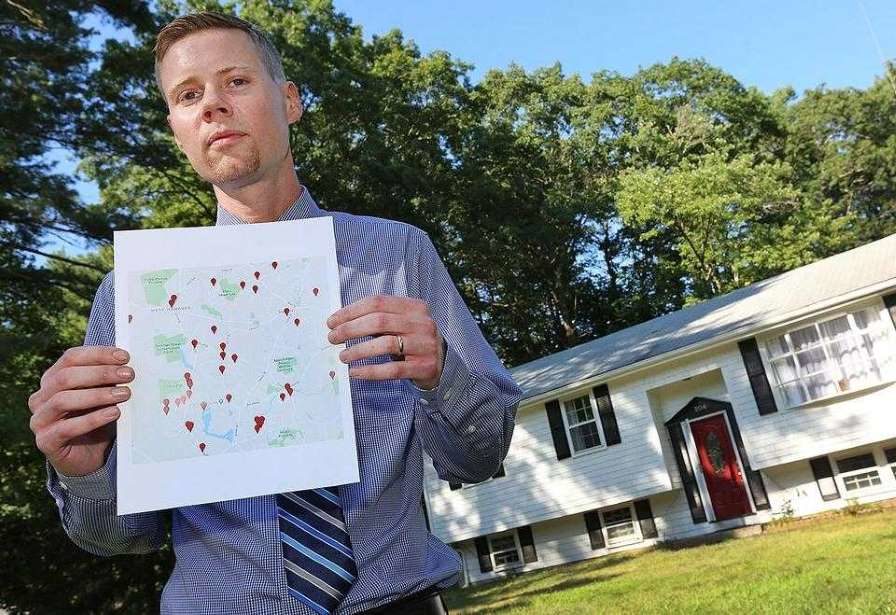

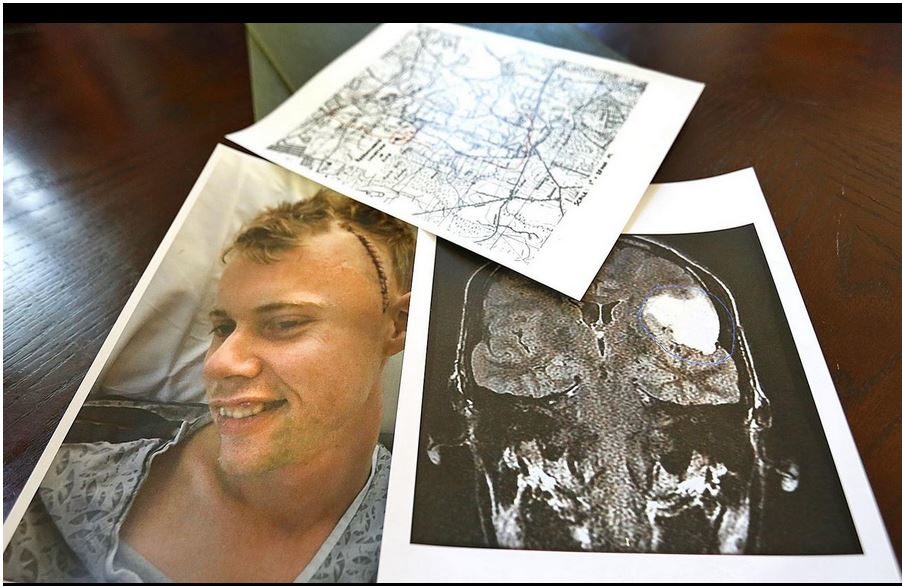

After being diagnosed in 2015 with oligodendroglioma, a rare brain tumor, Squires said he noticed that an alarming number of other young adults who grew up in his neighborhood were fighting, and dying, from brain tumors.

"These are exceedingly rare tumors, and I can name seven people off the top of my head who have brain cancer," said Squires, 34, now of Hanson. "There's just no way it's coincidental."

The number of new cases of brain and other nervous system cancers among the general population is about 6.4 per 100,000 people each year, according to the National Cancer Institute, and a 2005 report estimated about 2,014 people lived within a 1-mile radius of the site based on data from the late 1990s. Squires said based on that data, there should be maybe one person diagnosed with a brain tumor in the area around the fireworks site, not dozens.

"I had anxiety about coming out and talking about this because I know it can cause panic," said Squires, a married father of three children, including 4-month-old twin boys. "But there's something very wrong here, and people have the right to know."

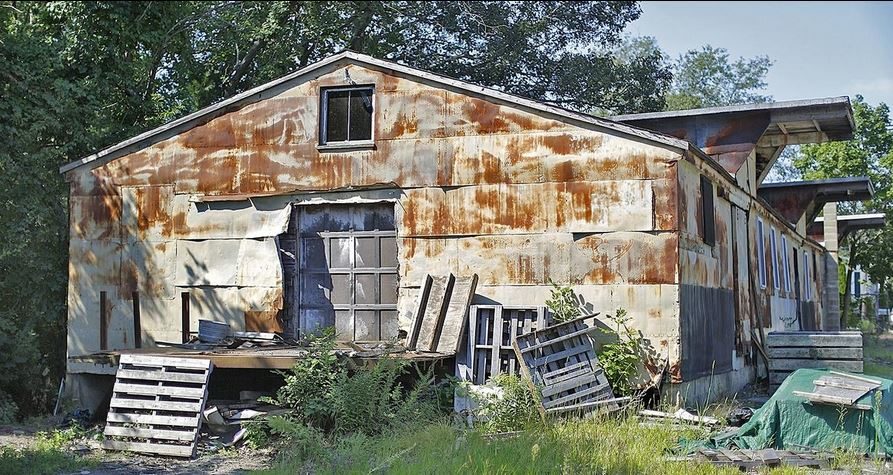

The National Fireworks Co. began developing, testing and manufacturing civilian fireworks and military munitions at the site near the Hanson town line in 1907, and disposed of chemicals there until it closed in 1971.

The property was then purchased by American Potash and Co., which operated there for a few years before selling the land to the Atlantic Research Corp., a government contractor that produced explosives for the Army and the Navy, and also allowed other entities, including the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to dump hazardous waste on its property.

In the mid-1980s, the federal Environmental Protection Agency found several dozen barrels of toxic waste around the property and indications that many had been dumped, according to several reports. Some of the toxins found include chloroform, Freon, arsenic, trichloroethene and vinyl chloride.

A variety of heavy metals, including mercury, were found in the soil and water around the former factory, setting off a decades-long effort to clean up 140 acres between King and Winter streets. While the contamination was measured at twice the threshold for earning Superfund status — a federal program that prioritizes and funds the cleanup of hazardous sites — town officials asked the state to oversee the cleanup to avoid the federal process and stigma that came with it.

"People deserve to know that the site saw more than 60 years of unadulterated contamination with chemicals I can't even pronounce, and not small quantities," Squires said, flipping through stacks of research and reports about the site he's collected.

A 2005 comprehensive site assessment report by Tetra Tech, an environmental firm, said at least 19 contaminants were found at the site.

"The findings indicate that there are areas of the site where there is a significant risk to both human health and the environment from the presence of a number of (chemicals of concern)," the report concluded. "Risks were found from exposure to the contaminants in biota, aquatic plants, soil, sediment, surface water and fish tissue at the site."

The state Department of Environmental Protection agreed in 2012 to oversee the cleanup - thus avoiding the Superfund stigma. In 2014, Hanover got $73 million for the work from a $5 billion federal settlement with Anadarko Petroleum.

Officials have long known that munition-related debris was probably buried in the former industrial site, which is now owned by the town and home to forested walking trails, but when excavation began in spring 2017, crews found far more undetonated munitions than expected and were forced to put in new engineering controls. Workers have now spent about three years digging up and detonating munitions on the property.

Squires said he thinks contamination spread well beyond the actual fireworks site, which was closed to the public only a couple of years ago. In 2014, the town completed construction of nearby Forge Pond Park off King Street.

But town officials have been urging residents not to jump to conclusions about links between the contamination at the fireworks site and any particular medical condition. Hanover Town Manager Joe Colangelo said he met with Squires earlier this year, and along with the board of selectmen asked the state Department of Public Health to investigate Squires' concerns regarding rates of brain cancer.

"I don't know at this point if it's a public health concern, and it's good to hold judgment on that until the study is done," Colangelo said. "We care both personally and professionally about any concerns in town, but it's important that we get factual information, and hopefully we do before drawing too many conclusions."

Ann Scales, a spokeswoman for the state Department of Public Health, said the agency is doing a "screening-level review" of brain and other nervous system cancers in census tracts near the former National Fireworks site. The review will look for unusual patterns of brain and other nervous system cancers over a 30-year period, compared to what would be expected.

Scales said the review will use data reported to the state's cancer registry, to which hospitals and facilities are required to report all cancer diagnoses among Massachusetts residents. Each report includes an individual's residence at the time of diagnosis.

But experts believe most cancers take anywhere from 10 to more than 50 years to develop, meaning those exposed to toxins at the fireworks site could have gotten cancer years after moving away, and therefore may not be accounted for in the data.

Molly Jacobs, project manager at the University of Massachusetts Lowell Center for Sustainable Production, said the cancer registry does not track past residencies, which limits its use in identifying cancer clusters.

"It's a lot more difficult to do investigations for adult cancers because people move, so if the registry doesn't show a cluster, it doesn't mean it didn't happen among those exposed who have since moved away," said Jacobs, who previously worked at the state Department of Public Health investigating disease clusters tied to exposure to contamination.

Squires, for example, lived on King Street in Hanover until he was 18, but wasn't diagnosed with brain cancer until he was 31 and living in another town. He likely won't show up in the data on brain cancer collected by the state.

The Massachusetts Cancer Registry was started in 1980 partly in response to a cancer cluster in Woburn. Between 1969 and 1986, nearly two dozen Woburn children were diagnosed with leukemia. It was later determined that hazardous chemicals dumped by local industry contaminated two drinking water wells and likely caused the high incidences of cancer.

Jacobs said the Woburn case involved children who had lived in the same neighborhood for most of their lives and were still there at the time of diagnosis, which allowed the registry to accurately reflect the increased rates of leukemia.

While the fireworks neighborhood data may turn out to be limited and perhaps inconclusive, Jacobs said it's important to raise awareness about potential health concerns.

"The fact that it is a hazardous waste site, we need to make sure people are safe, and kudos to (Squires) for raising concern that the exposures are truly being mitigating," she said.

The state Department of Environmental Protection last fall tested two irrigation wells on King Street used to water some of the town's recreational fields and did not find any evidence of volatile organic compounds or metals at unsafe levels. They did similar testing for an irrigation well on Birch Street. Colangelo, the town manager, said the town's drinking water comes from wells on the other side of town.

The report by Tetra Tech said six private drinking wells are within a half-mile of the site, including five in Hanson and one in Hanover.

Birgit Claus Henn, an assistant professor of environmental health at Boston University School of Public Health, said a true epidemiological study into the causes of health outcomes and diseases looks at dozens of factors, from when and how exposure happened, for how long, and what other characteristics those who got sick have in common. Even nailing down the size of the population to study can have huge impacts on outcomes.

"That's why when we do these studies, we collect so much information," she said. "In these situations, a single study isn't the end-all."

While some officials want to see hard evidence before jumping to conclusions, others who grew up and spent their childhoods in West Hanover say there's little doubt in their minds that there's a correlation between the contamination and cancer rates.

Like Squires, Rob Simmons spent much of his childhood hanging out in the neighborhood around the fireworks site. He was diagnosed with a pituitary adenoma, a tumor near the base of the brain, in 1999. After looking at the research done by Squires, Simmons said it seems more than just circumstantial that there are so many instances of brain tumors in one neighborhood.

"You hear stories in your peer group and in the back of your head wonder if these things are happening in other areas," Simmons, now living in Milton, said. "The map Nick put together of instances is pretty telling."

Paul Cignarella's sister, Julie, died five years ago at the age of 31 from pilocytic astrocytoma, a rare brain tumor that develops in childhood. He said his family deserves answers if the contamination they were exposed to while spending time in the woods caused her tumor.

"If people keep getting sick, pushing it under the carpet isn't doing anyone justice," he said.

This isn't the first time residents have questioned whether the contamination at the fireworks site has made people sick. A study released in 2007, prompted by a request a year earlier from concerned residents, examined high rates of thyroid cancer in Hanover and searched for a link to a chemical commonly used in explosives called perchlorate.

The state's evaluation found that between 1999 and 2003, rates of thyroid cancer in women in the southern part of town were more than four times the expected rate: Nine cases were reported when two were expected.

But the health report also looked at residential history of the women diagnosed with thyroid cancer and found that eight of them lived in Hanover for less than 10 years.

"Given that most cancers have long periods of development, between 10 and 40 years, their length of residence makes it unlikely that their place of residence played a role in their diagnosis," the report stated.

Dr. T. Stephen Jones, a public health consultant epidemiologist who retired from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2003, said clusters are "bedeviling" for epidemiologists and hard to evaluate. He said communities can request epidemiological assistance from the federal government, since they're often too intense for communities to tackle.

"These things aren't easy to do," he said.

Reach Jessica Trufant at jtrufant@patriotledger.com.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter