Yesterday afternoon, immediately after the Dallas Cowboys' hard-fought victory over the Seattle Seahawks, Fox's Erin Andrews interviewed Dallas quarterback Dak Prescott and running back Ezekiel Elliott. She asked Elliott what he thought when he saw Prescott take off for a key run that set up the winning touchdown.

"It's simple," Elliott responded, "He's a grown-ass man. That's what it is. That's how he played today, and he led us to this win."

That's a phrase you hear a lot in sports. "Grown man." There's grown-man football. There's grown-man basketball. It speaks to a certain style of play. Tough. Physical. Courageous. Overpowering. It's also fundamentally aspirational. It's quite safe to say that millions of young boys desire to become a grown man - a person who is physically and mentally tough, a person who can rise to a physical challenge and show leadership under stress. In fact, that's not just an intellectual goal, it's a deeply felt need. It's a response to their essential nature.

But becoming a true "grown man" - while a felt need - isn't an easy process. It involves shaping and molding. It requires mentoring. It requires fathers who are themselves grown men. Turning boys into grown men means taking many of their inherent characteristics - such as their aggression, their sense of adventure, and their default physical strength - and shaping them toward virtuous ends. A strong, aggressive risk-taker can be a criminal or a cop, for example. To borrow from the famous American Sniper speech, they can be a sheepdog or a wolf.

And if you're a father of a young boy or spend much time with young boys - especially if you coach boys in sports - you'll note a very human paradox. Even as they want to become the grown man they see in their father or in their idols, they'll often fiercely resist (especially at first) the process. They'll find the discipline oppressive. Building toughness requires enduring pain. And who likes enduring pain? Effective leaders have to have a degree of stoicism, but it can be hard to suppress natural emotions to see reality clearly.

Nothing about this process is easy. Some fathers default to cruelty as a teaching tool, with disastrous results. Others are deeply intolerant of differences, rejecting or even bullying those boys who don't conform to masculine norms - thus driving them into deep despair.

But while the process of raising that grown man isn't easy, it is necessary. Evidence of its necessity is all around us. While a male elite thrives in the upper echelons of commerce, government, the military, and sports, men are falling behind in school, committing suicide, and dying of overdoses at a horrifying rate, and their wages have been erratic - but still lower (in adjusted dollars) than they were two generations ago.

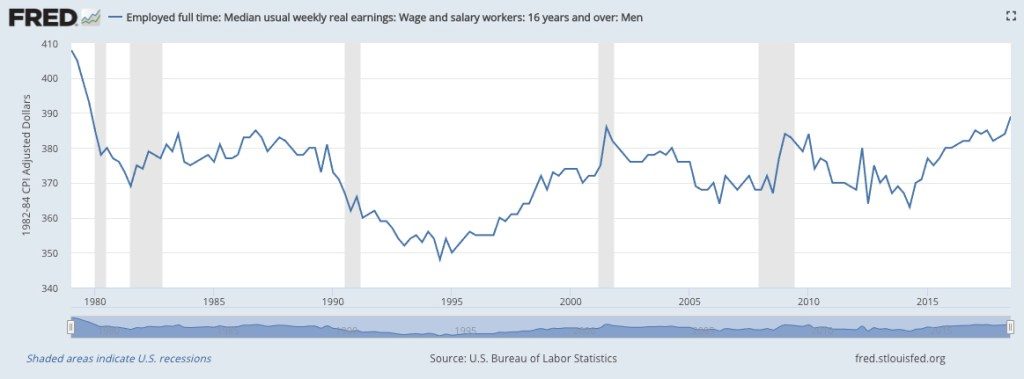

Men still make more money than women, but to see the differences in wage growth, compare these two charts from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Here are male wages since 1979:

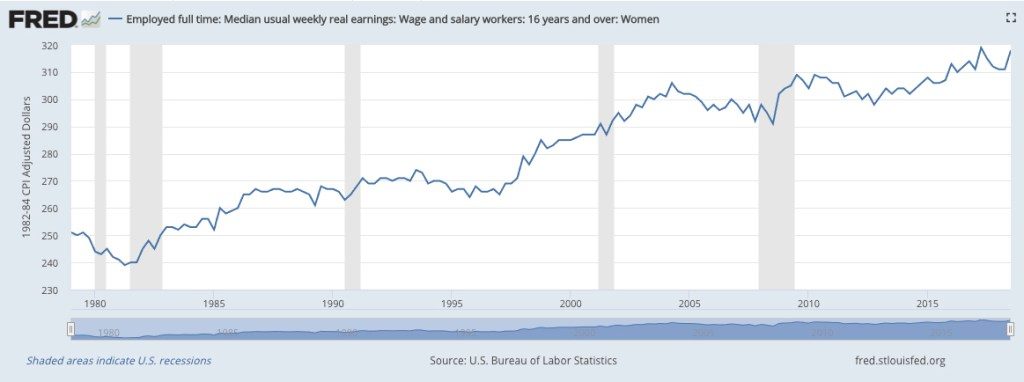

Contrast that chart with the positive story of the female economic revolution:

We are in the middle of an intense culture war focused around men, dominated at times by two kinds of men-as-victim narratives. On the populist right, you'll get those voices - such as Tucker Carlson - who see these trends and rightly decry them, but then wrongly ascribe an immense share of the negative results of immense social, economic, and cultural changes to the malice or indifference of elites, with solutions wrongly centered around government action.

Carlson has triggered a critical debate on the right, but then - just in time to remind us that well-meaning people from all sides of the political spectrum can propose solutions worse than the disease - along comes the American Psychological Association with its first-ever "Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men." The APA sees the challenges facing young men and rightly seeks to overcome those challenges, but then diagnoses the wrong cause. As Stephanie Pappas notes on the APA website, the new guidelines conclude that "traditional masculinity - marked by stoicism, competitiveness, dominance, and aggression - is, on the whole, harmful."

Comment: It looks pretty clear that the APA has been infested by the pathology of fourth wave feminism. This is a very bad sign for the future of psychology in the West.

The guidelines themselves argue that "traditional masculinity ideology" - defined as socializing boys toward "anti-femininity, achievement, eschewal of the appearance of weakness, and adventure, risk, and violence" - has been shown to "limit males' psychological development, constrain their behavior, result in gender role strain and gender role conflict," and negatively influence mental and physical health.

Yet as we survey a culture that is rapidly attempting to enforce norms hostile to traditional masculinity, are men flourishing? And if men are struggling more the farther we move from those traditional norms, is the answer to continue denying and suppressing a boy's essential nature? Male children are falling behind in school not because schools indulge their risk-taking and adventurousness but often because they relentlessly suppress boys and sometimes punish boys' essential nature, from the opening bell to the close of the day. Especially in fatherless homes, female-dominated elementary-school experiences often mean that boys are exposed to few - if any - male role models, and male restlessness is therefore viewed almost entirely as a problem to be solved rather than a potential asset to be shaped.

It is interesting that in a world that otherwise teaches boys and girls to "be yourself," that rule often applies to everyone but the "traditional" male who has traditional male impulses and characteristics. Then, they're a problem. Then, they're often deemed toxic. Combine this reality with a new economy that doesn't naturally favor physical strength and physical courage to the same extent, and it's easy to see how men struggle.

As I've argued before, acculturation into healthy traditional masculinity used to be a far more natural and inevitable act. Even upper-class men had to learn to work (at least to some degree) with their hands; to earn a living, working-class men often had to be strong; and with more intact families (and male-dominated work spaces), men did not lack for role models.

That does not mean that men were perfect. There is already too much nostalgia in our society for a past that had virtues but also had terrible vices. But it does mean that it was easier for a man to have purpose, and meaningful and sustainable happiness is elusive without purpose.

Now, acculturation into healthy traditional masculinity has to be far more intentional. Why should a man who works in a cubicle and types on a keyboard all day be strong? How does he productively satisfy that quest for adventure? How do you shape an identity as a sheepdog in safe suburbia? Why be stoic at all when everyone around you is indulging in the emotionalism that's often a hallmark of "self-care"?

All of this is hard. Very hard. Especially when combined with the fact I mentioned at the start of the piece - the creation of a "grown man" involves short-term pain. As with so many things, we want the result, but we hate the process. Effective role models understand this reality, and they preach relentlessly about the worth of sacrifice.

Take, for example, one of the world's most popular celebrities, Dwayne Johnson (better known as "The Rock"). He shares a mantra for life improvement that particularly resonates with young men - "blood, sweat, and respect." You sweat and bleed and in return you earn respect. It's a more vivid version of "no pain, no gain." Virtuous traditional masculinity is inherently incompatible with a pain-avoidance culture.

Let me close with a story I've told before. I've spent most of my career as a litigator and most of my recreational time as a nerd. Given that reality, it's very easy to get soft. There's nothing about writing legal briefs or reading The Silmarillion for the tenth time that builds your biceps. I was an active kid, and I played basketball in leagues into my early 30s, but when I aged out of my league, I started to surrender to my desk job. I gained weight. I couldn't run even a mile without gasping for air.

And I was deeply unhappy with myself. So I did something about it. I put down Tolkien, logged off World of Warcraft (well, for a few minutes anyway), and started running again. I joined the Army and got stronger before I left for my officer basic course. I got stronger still before I left for Iraq. I was stronger still by the time I came home.

Then, one day after I returned from overseas, I was on a Cub Scout hike with my son. We were at the bottom of a ravine, when one of the boys threw a rock that hit my son square in the head. The gash was deep, blood was everywhere, and he started to lose consciousness. Our cell phones worked to call 911, but there was no way the ambulance could come down to us. We had to run up to it.

So, with the pack leader applying direct pressure to his head, I picked him up and started to run - straight up a steep incline. I ran, carrying him, until I was about to pass out. Then my wife (who is very strong but couldn't carry him as far) would spell me for a bit. Then I'd grab him and run some more. We got to the top of the hill just as the ambulance arrived, and they were able to stop the bleeding before the blood loss got too serious.

A few years before, I would have collapsed, wheezing on the ground, after carrying a third-grader even 100 yards uphill. I would have failed my own son. But I answered the call of my "traditional masculinity" and got stronger not because I wanted to look good or attract women or "be fit" but because something inside me whispered that an able-bodied man should not be weak. In other words, I tried my best to become a true "grown man."

We do our sons no favors when we tell them that they don't have to answer that voice inside them that tells them to be strong, to be brave, and to lead. We do them no favors when we let them abandon the quest to become a grown man when that quest gets hard. Yes, we do them no favors when we're not sensitive to those boys who don't conform to traditional masculinity, but when it comes to the crisis besetting our young men, traditional masculinity isn't the problem; it can be part of the cure.

Reader Comments

Just be your natural bloke self. Male impersonators need not apply.

"We do our Sons no favors" ... nor our Daughters. Nor our communities, or our society.

If anyone should be encouraged to "Man Up" right now, it's our men, our young boys.

For a good part of my adult life women were told to "man up", men were told to "get in touch with their feminine side". Didn't necessarily sound like a bad thing at the time, but Oh My God, it is spiraling into something so deranged.

Women are Strong, have always been. Men are compassionate and caring, have always been. This "flipping" of imposed 'gender' roles, and 'gender' even, is just demented. A bad path for humanity.

Thank God for Jordan Peterson.

Their ticket should be withdrawn for corruption. Strip them of their funding, all professional privileges. They are then free to say what they like all on their own. And welcome too it. For as long as they can stick it out. Which being a typical bunch of academic racketeers, won't be very long.