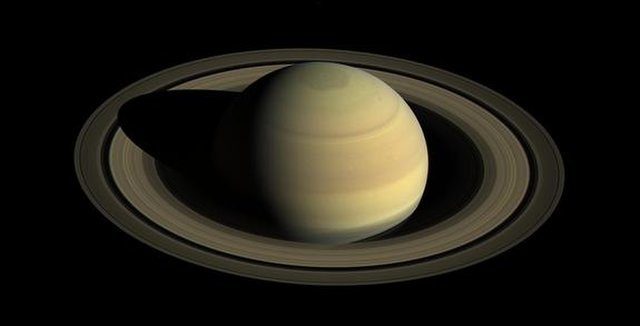

The Cassini spacecraft captured this stunning view of Saturn and its rings on April 25, 2016.

That's the conclusion of a new investigation into a phenomenon called "ring rain," which pulls water out of Saturn's rings and into the planet's midlatitude regions. Combined with earlier research this year using Cassini data to look at a different type of inflow from the rings to the planet, that find means the stunning structures could be gone in as little as 100 million years.

"We are lucky to be around to see Saturn's ring system, which appears to be in the middle of its lifetime," lead author James O'Donoghue, a space physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, said in a statement. "However, if rings are temporary, perhaps we just missed out on seeing giant ring systems of Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, which have only thin ringlets today!"

The new research relies on ground-based observations gathered over a couple of hours in 2011 from Hawaii of a special form of hydrogen that glows in infrared light. That specific form of hydrogen makes up "ring rain," a phenomenon scientists have been working to pin down for decades.

And the results were stark: If the sheer volume of ring rain the scientists spotted during those few hours is typical for Saturn's weather forecast, that rain would eat up a huge amount of the icy rings, between 925 and 6,000 lbs. (420 to 2,800 kilograms) every second. That rate, combined with the current mass of Saturn's rings, is what lets scientists calculate that 300-million-year life expectancy, although the large range on the infall calculation means there's quite a bit of uncertainty about the rings' lifetime.

The fate of the rings looks even grimmer considering research published earlier this year using Cassini data, which looked at a different, still-more-voluminous, type of infall from Saturn's rings that's descending into the planet. O'Donoghue and his co-authors didn't include that infall in the estimates presented in their paper, but suggested in an accompanying statement that the two phenomena combined could gorge through the rings in more like 100 million years.

The research is described in a paper published yesterday (Dec. 17) in the journal Icarus.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom and Facebook.

Comment: Were Saturn's rings always disappearing so fast and it was merely a matter of measurement? Or has the process actually begun to speed up? Could it be related to the other diverse and increasing changes we see throughout our solar system?

- Cosmic climate change: Is the cause of all this extreme weather to be found in outer space?

- Stargate? Saturn sprouts another weird hexagon

- Stunning side-by-side video of Mars shows how the planet-wide dust storm has transformed the surface of the red planet

- Solar minimum is upon us and 20 years of data shows other stars are exhibiting similar signs

- Solar System-wide 'climate change': Jupiter's moon Io seeing increasing volcanic activity

- Earth's magnetic field is drifting westward

Also check out SOTT radio's: Behind the Headlines: Earth changes in an electric universe: Is climate change really man-made?