© Nguyen Huy KhamA Hmong woman carries grass in Vietnam.

In Thailand, a small group of Hmong women lived in a rural village, far from the nearest town. They grew everything they ate, mostly rice and vegetables. They boiled most of their food, and they rarely consumed meat.

But then something happened to these Hmong women that shocked their systems, permanently altering, in just a short time, the course of their health-as well as the very germs that dwelled inside of them. They immigrated to the United States.

In their new homeland-Minneapolis-they began to eat more protein, sugar, and fat. They indulged, like most Americans do, in processed food. Within a generation, the Hmong women went from having an obesity rate of 5 percent to one of more than 30 percent.

That statistic reflects one of the most vexing things about the well-being of immigrants in the U.S.: Many people who come to the U.S. for a better life end up with worse health. Many different studies have now shown that the longer certain groups live in the U.S., the worse some of their

health outcomes get, especially when it comes to

obesity. One study found that after one year in America, just 8 percent of immigrants are obese, but among those who have lived in the U.S. for 15 years, the obesity

rate is 19 percent.

Using stool samples and dietary surveys from Hmong women living in Minneapolis, researchers from the University of Minnesota decided to see if the gut microbiome - the colony of bacteria that dwells in our intestinal tract-might play a role in immigrants' obesity rates. In addition to Hmong immigrants, they recruited a group of Korean women who had previously lived in a refugee camp in Thailand. There, they had foraged in a nearby forest for food and had also eaten primarily rice and vegetables.

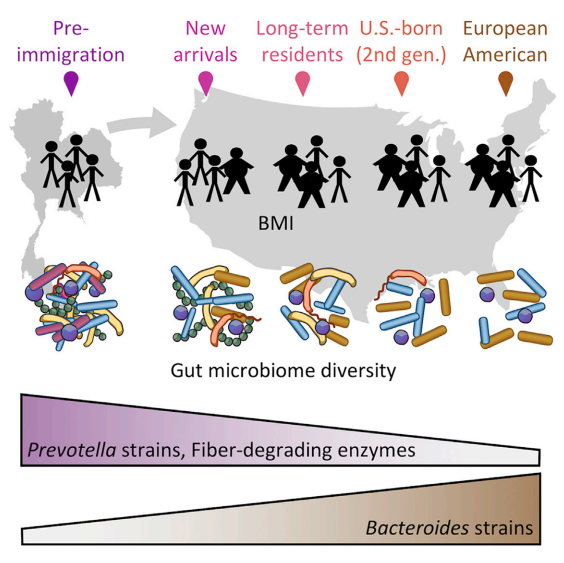

The researchers compared the gut microbiota of Hmong and Korean women still living in Thailand with the gut microbiota of three groups: Hmong and Korean women who had immigrated to the U.S., these immigrants' American-born children, and white American controls. The researchers also followed one group of 19 Korean refugees from their time in Thailand through their move to the U.S., tracking the components of their microbiota during their first year in America. (They limited the study to women because substantially more Hmong women than men were immigrating to the U.S.)

After about nine months in the U.S., the researchers found, the immigrants' gut microbiomes had began to "westernize." The microbiomes became less diverse-teeming with fewer types of bacteria-which is often associated with obesity. "Having low diversity in your microbiome is almost universally a sign of bad health, across almost every disease that has been studied," says Dan Knights, a computational microbiologist at the University of Minnesota and a co-author of the study, which was published Thursday in the

journal Cell.

The immigrants' microbes became less able to digest certain types of fiber, and they shifted from being dominated by a type of bacteria called

Prevotella to one called

Bacteroides. Their gut microbiota, in other words, came to resemble those of the white Americans who acted as the control. The microbiome changes were even more pronounced among obese participants and in second-generation immigrants who were born in the U.S.

© Cell

While the fact that microbiomes change as people move into different types of societies was already known, "to watch it happen six to nine months after people moved is startling," says Justin Sonnenburg, a Stanford microbiologist who was not involved with the study.

However, this paper only showed that there is a correlation between westernization of the microbiome and obesity, not that one causes the other. And that's a key piece of the microbiome puzzle that scientists are still missing. We don't know if eating a less-healthy diet makes you obese

and changes your microbiome, or if it changes your microbiome

so it makes you obese.

Kelly Swanson, a nutritionist at the University of Illinois, for one, says that while "the microbiota are important for health, I don't blame the obesity on bacteria. There are other things driving the ship."

There is some evidence that bacteria alone can spur weight gain. In 2013, when scientists

took the gut bacteria from one fat human twin and one skinny twin and implanted them into mice, the mice that received the fat twin's bacteria grew fat, while the skinny-twin mice stayed thin. What's more, when the mice were housed together, they tended to eat one another's poop. When that happened, the skinny-twin bacteria would invade and colonize the guts of the other mice, even though the other mice had already been given the fat-twin bacteria. Those invaded mice, in turn, would lose weight. This meant "lean" gut bacteria can sometimes invade and conquer "fat" bacteria, but not, in this case, the other way around.

Here's the twist: In that experiment, it was

Bacteroides, the same bacteria that ended up dominating the immigrants' microbes, that did the colonizing and the tamping down of the "fat" bacteria. In other words, even though it's been associated with

various diseases, it looks like

Bacteroides can, in some cases, be a good guy. "And that's one of the million-dollar questions: Are these [microbiome] changes bad?" Sonnenburg says.

After all, it's little surprise that our microbes might change with our diets. The

Prevotella strains that were wiped out among the Hmong and Korean people were used for digesting foods like tamarind, palm, and coconut. "It makes sense that if people stopped eating those foods, the microbes that used to subsist on them would go away," Knights says.

What's more, the microbiomes of the immigrants seemed to change faster than the diets did: Even after they moved to the U.S., the immigrants ate 10 times more rice than the Americans. "That tells us there's probably something else going on that we weren't able to observe," Knights says, such as exposure to medication or some other environmental change.

The researchers I spoke with praised the study, but they said we still need more like it. Alas, the subtle work of the microbiome is not as glaring as the

processed foods that bombard Americans-new and old-at every turn.

Reader Comments

...over weight by their own

[Link]

And so the prescriptive advice is to cease consumption of processed crap, tip your drug medication into the toilet, clean up your act and go live life. Stop paying the medical racketeers.