As Iran tries to gain assurances from China that it will remain in the deal, the US Department of Commerce has banned American firms from selling parts to ZTE, one of China's largest IT companies, for seven years and fined the company $1.1 billion for violating sanctions against Iran and North Korea. The need to have American parts for the company's production line has brought it to near bankruptcy. Now, US President Donald Trump is suddenly moving to reach a solution to ZTE's fate. The parallel timing of these events highlights the complicated position Iran is faced with to win China's support.

Beijing is Tehran's first trade partner; in addition to being the biggest buyer of Iranian oil, it is a key political partner. In 2017, the volume of trade between the two countries was estimated at $37.18 billion, 13% higher than the year before. China is also one of the few foreign investors in Iran. Its state-owned energy giant China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) has a 30% stake in a multibillion-euro agreement to develop phase 11 of Iran's South Pars, the world's largest gas field. The contract was the biggest energy deal to be reached following the signing of the JCPOA. With French consortium partner Total potentially having to pull out due to US sanctions, CNPC's share of phase 11 could further increase. China has also signed a $10 billion financing deal to support projects in Iran, the biggest credit line secured since the nuclear deal was signed.

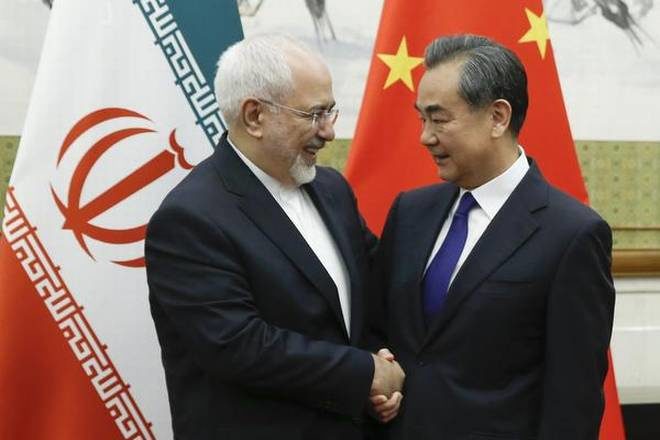

At the political level, Chinese President Xi Jinping was quick in traveling to Iran following the implementation of the JCPOA in January 2016. His visit led to the signing of 17 bilateral agreements and included discussions on setting up a 25-year roadmap to broaden relations and expand trade. The two countries also agreed to increase bilateral trade to $600 billion in the next 10 years.

Therefore, it would appear that China, as one of Iran's key economic and political partners, would have great interest in preserving the JCPOA and that the Islamic Republic should thus seek comfort in knowing that it has Beijing's support. However, if the economic interactions between Iran and China are viewed in the context of Beijing's total foreign trade as the world's second-largest economy, it becomes uncertain as to how comfortable Iran can truly feel. Last year, China's foreign trade stood at $4.28 trillion, of which trade with Iran accounted for less than 1%. This is while the United States is China's second trade partner; in 2017, bilateral trade stood at an estimated $636 billion, 17 times higher than the volume of trade between Iran and China.

Chinese exports to the United States account for $506 billion of the $636 billion in bilateral trade. Moreover, 90% of China's trade comes from the private sector, of which multinational companies account for 40%. Thus, China - like the European Union - is facing a complicated situation in continuing its economic interactions with Iran. The problems that ZTE is facing for violating sanctions against Iran and North Korea are indicative of this point. Therefore, given Beijing's vast economic interests in the United States in line with its cost-benefit calculations, China and Chinese companies have no choice but to gradually adapt themselves to the reinstatement of US sanctions against Iran.

However, the JCPOA is more than just an economic agreement. As a major world power, China also has an international responsibility for the future of the rules-based international order; this could potentially give rise to a third scenario for how China may act within a JCPOA without the United States.

With the US withdrawal, China - again, like the EU - is faced with the challenge of creating a balance between its multilateral interests. Indeed, it will be challenging for it to find an equilibrium between its massive trade interests with the United States, its broader national interests as well as its international responsibilities as an emerging power. With Xi as president, China's foreign policy is gradually changing from one of low-profile diplomacy to having a more extensive role in world politics. China views a rules-based international order that is founded on multilateralism as serving its interests. In this vein, the unilateral US decision to pull out of the JCPOA is a destabilizing move that also weakens the nonproliferation regime. Given that the withdrawal additionally negatively impacts the UN Security Council, which adopted the nuclear deal in Resolution 2231, the US exit from the nuclear deal goes against China's greater foreign policy strategy.

Furthermore, China-US relations are gradually moving toward a paradigm shift. On the one hand, the US strategy of engagement with the intention of peacefully evolving China's political system to a liberal democracy has been met with defeat. On the other hand, an increasing number of Chinese elites are of the belief that the United States is seeking to contain China. This view is somewhat confirmed by the increased emphasis of international leaders on rising great power competition. At the same time, US political discourse generally defines China, Russia, Iran and North Korea as the biggest threats to American interests.

The US withdrawal from the JCPOA can also lead to greater instability in the Middle East and pave the ground for a radical change in the regional balance of power. Such changes will harm China's interests in West Asia. More than half of China's oil imports come from the Persian Gulf region, leaving its energy security exposed to local developments. A change in the regional power balance against Iran will also damage China's presence and influence in the Middle East.

With the United States leaving the JCPOA, China will most likely try to maintain the fragile balance between its many interests. Beijing may seek new ways to maintain at least a minimum level of economic interaction with Iran while at the same time adapting itself to the new sanctions. The experience of the previous round of sanctions will likely be useful here.

China's response in the current situation will also be greatly influenced by the actions of the EU. In other words, if the responsibility for upholding the economic dividends for Iran promised under the nuclear deal is divided between these two key trade powers, they will both feel less pressure on Iran and the JCPOA. Of course, China will most likely have no desire to be the leader in preserving a JCPOA without the United States and will instead prefer to give this role to the EU. Indeed, playing a key role in resolving the crisis on the Korean Peninsula will likely be more of a priority for China in the coming months.

Mohsen Shariatinia is an assistant professor of regional studies at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran. On Twitter: @m_shariatinia

USA is getting away with "murder" in this case and it seems that

China is being PUT in it's "right place" by the Empire...

The DOLLARS are speaking more LOUDER!!!... It seems...