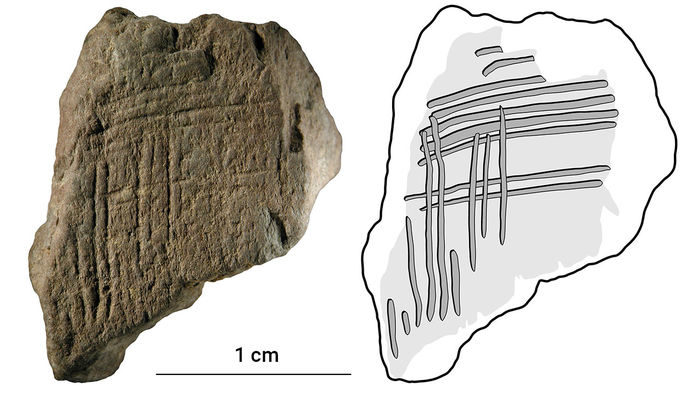

To come to this conclusion, Kristian Tylén, a cognitive scientist at Aarhus University in Denmark, and his team of cognitive scientists and archaeologists took a closer look at dozens of etched red ochre stones found in the cave, known as Blombos Cave. Some scientists have called the markings early forms of art and even evidence of symbolic behavior, such as full-blown language. Tylén's group also looked at a set of ostrich egg shells with engraved lines, parallel lines, and ladderlike images found at another site in South Africa. The markings date to between about 52,000 to 109,000 years ago, after the birth of our species but before widespread artistic expression such as cave paintings of animals.

Tylén figured that if the marks were chiefly decorative, created because someone enjoyed looking at the pattern, the eyes of living humans would be able to see the patterns easily. If the markings were cultural traditions, they would need to be memorable, because the cave dwellers may have had to make them multiple times. And in that case, people today also ought to able to remember and copy them. Over time, the markings from each locality ought to also become more distinct, because a maker in one place wouldn't want the scratches to be confused with those in another place.

And if the markings were truly symbolic-if a line, for instance, represented the horizon, or a series of wavy lines represented the ocean-then the symbols would have to be distinguishable from one another, and they also would become more distinct from each other over time. To take a modern example, different emojis couldn't work as symbols if they all looked the same.

Tylén asked 65 Danish university students to examine 24 cleaned-up images of the original stone or shell markings, and then perform tasks such as sorting or copying the lines. The researchers wanted to know whether people could tell the marks from one site from those from the other, and whether they could copy them after looking at them briefly.

The most complicated test involved showing one marking to one of a person's eyes while overwhelming their brains with a field of flickering colors in their other eye. It took from 2 to 12 seconds for the markings to "break through" into a person's conscious perception. For any given viewer, more recent markings "broke through" more quickly than older ones, suggesting that the humans making them honed the engravings' visual distinctiveness over the millennia.

Tylén's team found that, in the eyes of today's humans, younger markings had more clearly defined visual elements and were more aesthetically regular than older ones. Participants also could remember and reproduce the more recent markings better than the older ones. But people weren't able to sort the markings into the correct groupings by place, and weren't able to distinguish signs from each other.

That's a minimal test of being a symbol-being distinct from another marking-and the engravings failed. "That suggests that we're not looking at a symbolic system in the sense that each marking has an individual meaning," Tylén said to meeting attendees.

Given the small sample, Cory Stade, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom who attended Tylén's talk, says the findings are more suggestive than definitive. But she was intrigued by the method. "Archaeologists often assume that early engravings are symbolic but they don't have a way to test them," she says. "This approach would make it easier for more archaeologists to consider language and cognition," which are difficult to understand from stone tools or bones.

Archaeologist Ewa Dutkiewicz from the University of Tübingen in Germany, who studies lines of dots and crosses on 40,000-year-old figurines from southwestern Germany, agrees. She's convinced that the markings on her figurines are symbols, but would like to apply Tylén's methods to learn more.

I cannot imagine anyone really believing this theory. Harder still is imagining someone keeping a straight face while announcing this as serious scientific work.