Maybe you messed up a critical job interview, a keynote speech, a text to your significant other, an introduction to a new connection, a presentation, or a test.

We've all experienced sizable failures one way or the other.

Are you the type of person to just "go for it and hope for the best?" Here's some advice.

Don't.

Actually, do go for it, but only after you've thought through and evaluated these three cognitive biases extensively.

- Your confirmation bias.

- The impact of anchoring information

- Loss aversion that creates mistiming and lost opportunities.

On Bias

Biases can be helpful and efficient, but also dangerous. Confirmation bias, for instance, leads people to affirm their own viewpoints even in the face of incontrovertible evidence. This happens frequently in politics.

To best understand bias, we need to understand the common mental frameworks that approximate how an average person thinks.

In other words, we need to know the set of ways in which people think.

When looking at the field of cognitive psychology in relation to decision making, there are two main models you can use.

- The Intuitive Mindset. This mindset characterizes people who just seem to know what they're doing and seem to have behaviors and actions that flow naturally outward. Their intentions, associations, thinking, and other parts of their cognition and social influence are very fluid and adaptable. You're probably in this mindset when you're making small talk, walking, or doing some other activity like basic addition.

- The Reflective Mindset. At the opposite end of the spectrum there's the reflective mindset, which almost contradicts the effortlessness and fluidity displayed by the intuitive mindset. In school, you might have known some people that just breezed through exams while others needed a ton of preparation a few nights beforehand and several study strategies. The latter embodies the reflective mindset, which is more self-aware of its shortcomings and in touch with its mistakes.

In comparing the differences between these two mindsets, you'll find that while the intuitive mindset is often more efficient and elegant in its execution, it often cannot explain itself or correct its mistakes easily. Meanwhile, the clumsier reflective mindset catches errors much better and allows one to evaluate why an error might be being made and give deeper thought to the problem.

Anyways, understanding the interplay between these two mindsets is important for approaching the issue of cognitive bias because cognitive biases are much more complicated to capture than the above conceptualizations.

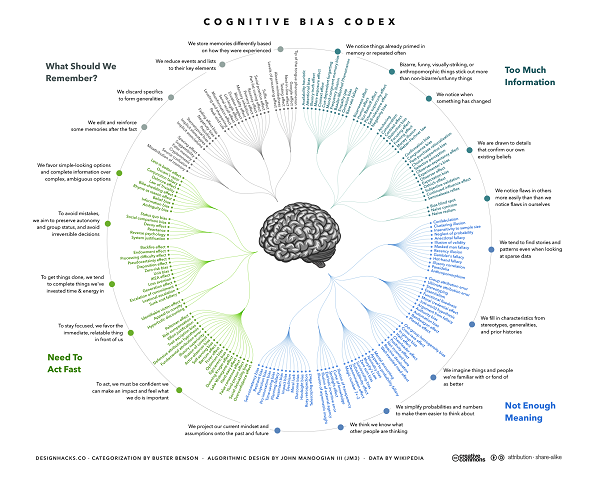

Just look at this list.

Here's the point.

You're not going to remember all of that and you're not going to have the supercomputer-like ability to factor all of these possible biases into your final judgment.

So instead, you want to apply the intuitive-reflective mindsets model as a heuristic for determining how biased you are before making a decision. You want to be aware of how intuitive and how reflective your actions are when you're executing a certain task and optimize or balance the two in a way that mitigates risk.

Let's use the example of an ice skater who's practiced her skills from childhood. If she starts thinking too much in the middle of a multi-spin trick on ice, then the shift from the intuitive mindset to the reflective one might cause her to stumble and fall instead of making a graceful landing.

This is analogous to how you might skillfully engage big business decisions with this knowledge.

Anchoring Information

This is probably a new one.

Anchoring information is a bit similar to confirmation bias, but it's not exactly the same thing once we consider a few illustrative examples.

But before that, the general idea of anchoring information is that people are predisposed to rely on the first piece of information they receive about an idea as correct and true rather than what they hear later on.

A funny example probably has happened to you before where you misremember someone's name and you keep on calling them that wrong name instead of their real one. That's the cognitive bias of anchoring information where the first name your mind remembers creates a strong impression for the rest of your relationship with that individual.

What about commonly misheard phrases? Have you ever come across someone who thought the phrase for "for all intents and purposes" was "for all intensive purposes," and adamantly insisted on it until you showed them on your phone or something? That's the anchoring effect in an informal setting.

In a business setting, anchoring may manifest when recommendations are made by consultants or when data is initially presented. Or, maybe your close friend has some special advice or expertise in an area that you've heard about too. Whatever the case, the effect of anchoring has the ability to lead you, in confidence, straight down the wrong road.

When you get a recommendation, or when you make a calculation based on some model, make sure that you're giving equal weight in consideration to all viable options and recommendations.

Try not to give more emphasis or trust to the ones you hear first sequentially. Get into the reflective mindset for a bit and ask yourself, "Am I fairly evaluating the situation, the data, or the recommendations and not just going with what I've heard first?" before you make that big choice.

Loss Aversion

Again, one thing that you, your team, or your company needs to think about when making any decision, is risk. Loss aversion is a bias surrounding whether or not one's desire to make gains is greater than one's tolerance to loss from risks when making those gains.

When making big decisions, try not to be overly cautious, even if what's riding on the line is huge. In order to keep a rational, calm mindset and make the best possible bets, you'll need to have a strong control over your feelings of loss aversion.

Some common examples of when loss aversion and cautionary mindsets might kick in and make you lose out during a big decision might be in gambling. Imagine playing a game of Blackjack for $10, $100, and $1000 and you can see how the psychology changes.

But, in this metaphor, if you're able to make rational decisions and treat the $1000 Blackjack bet like the $10 Blackjack bet, then your chances of losing as a result of your own loss aversion is minimized.

You can extend this gambling metaphor to risk taking in business. You don't want to be too risky to the point where you're not accounting for any costs and recklessly spending, but being too cautious also represents a problem that receives less attention.

Avoid loss aversion or at least minimize it and it'll allow you to navigate big decisions and wins like you do with small decisions and wins.

Overall, a balance between awareness and intuition is key to success when making a big risk or decision.

clumsier ?

CLUMSY [ME clumsid, numb with cold, pp. of clumsen, to benumb < ON base akin to Swed dial klummsen, to benumb with the cold]

1 lacking grace or skill in movement; awkward

2 awkwardly shaped or made; ill-constructed

3 badly contrived; inelegant

"Intuition" has also been a source of apprehending errors.

This entire article sounds like confirmation bias to me.