Heather Holland, a second-grade teacher, came home feeling a little sick on the last Monday in January.

"It just sounded like her throat was scratchy," said her husband, Frank Holland, a discomfort easy to ignore at first for a working mother. Over the next days, she made seemingly inconsequential decisions, including skipping a medicine because of the cost. Then her symptoms suddenly worsened, eventually sending Ms. Holland, 38 years old, to the hospital, on the brink of death.

Her battle was among the most severe fought during this influenza season, America's worst in a decade. It has taken the U.S. by surprise, pitting a weak flu vaccine against particularly virulent strains.

Most people recover within a few days from the aches, fever and cough as their immune systems drive out the infection. Thousands, however, have been treated this year at hospitals for pneumonia and other complications, including seemingly healthy adults with no underlying medical problems.

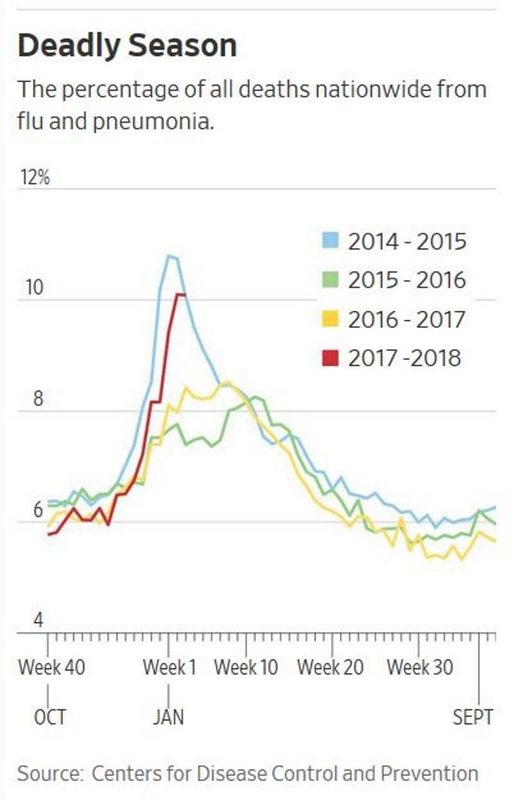

Rates of hospitalization are the highest since 2010, and the rate of reported flu illness is now as high as it was during the 2009 global flu pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Friday.

The percentage of all deaths in the U.S. from flu and pneumonia has risen to one of the highest levels in recent flu seasons. The flu kills between 12,000 and 56,000 people in the U.S. a year, according to the CDC, which estimates that this season's death toll will be at the upper range. The elderly are most at risk, along with young children.

"This is not the common cold," said Tim Uyeki, chief medical officer in the influenza division of the CDC.

Complications can arise when the body's immune system overreacts, triggering an exaggerated inflammatory response that can lead to viral pneumonia, organ damage or sepsis, a bloodstream infection, Dr. Uyeki said. Or, flu infection sometimes makes it easier for bacteria to invade the bloodstream, leading to a bacterial pneumonia that can also trigger sepsis, he said.

In both cases, people with the flu can quickly become critically ill, suffering a high fever or abnormally low temperatures and shortness of breath.

The dominant flu virus this year, an influenza A strain known as H3N2, is known for its severity, according to the CDC, but both the A and B strains have proven deadly in past weeks.

The vaccine this year isn't very effective-according to the CDC, as well as studies in other countries - but it can reduce the severity of the flu.

Karlie Slaven missed her flu shot this season, said her father, who is now urging others to get the vaccine.

Comment: A very bad idea.

- Roche's Tamiflu Not Proven to Cut Flu Complications

- Side effects from Tamiflu are worse than the flu

- Tamiflu Anti-Viral Drug Revealed as Hoax: Roche Studies Based on Scientific Fraud

- Tamiflu Vaccine Linked With Convulsions, Delirium and Bizarre Deaths

Ms. Slaven had nursed her two children through the flu in mid-January. Then the 37-year-old administrator from Plainfield, Ind., caught the virus. A day after she was diagnosed with the flu, Ms. Slaven was short of breath and went to a hospital emergency room. X-rays showed no problems, said her father, Karl Illg. She got medication and went home.

He and his wife went to Ms. Slaven's house. His wife took Ms. Slaven to the emergency room, while Mr. Illg stayed with their 11-year-old grandson and 9-year-old granddaughter.

A couple of hours later, his wife called and told him to bring the children to the hospital. Ms. Slaven was in critical condition. Her husband was reached en route to his deployment and was headed back.

Mr. Illg said he was struck by how quickly his daughter had become gravely ill. Two days earlier, she had common flu symptoms. At the hospital, he said, she could barely flutter her eyelids.

Ms. Slaven died early the next morning, less than three days after learning she had the flu.

'We're pretty healthy'

Ms. Holland, the second-grade teacher, didn't think much of her symptoms that Monday night, Jan. 29, at home in Willow Park, Texas, just west of Fort Worth. She went to school Tuesday. By nighttime, though, she had a fever.

On Wednesday morning, Ms. Holland dropped her 10-year-old daughter and 7-year-old son at school and went to her doctor, said her husband, an environmental scientist for an engineering firm. By then, schools had closed in at least 11 states to try to arrest the spread of the virus, which accelerated after children returned to campuses from winter break, CDC officials said.

A rapid flu test came back positive for influenza B, Mr. Holland said. The doctor wrote Ms. Holland a prescription for oseltamivir phosphate, a generic form of the antiviral medication Tamiflu, which can reduce flu symptoms when started early in the course of the illness.

After bringing their children home from church that night, Mr. Holland discovered his wife was taking Nyquil, he said. She told him she thought the price of the antiviral was ridiculous. He went to the pharmacy Thursday morning and got it filled himself. "I made her start taking it," he said.

Looking back, he said, he wished she and other teachers had better drug coverage, given their exposure.

Ms. Holland kept herself quarantined in the couple's bedroom. By Thursday evening, "she seemed like she was turning the corner," Mr. Holland said.

Still, when she came out of their room, he told her to go back and lie down. He made her some soup and slept on the couch.

Ms. Holland usually got a flu shot, but Mr. Holland couldn't remember whether she got one this season. The couple didn't go to doctors much. "Generally we're pretty healthy individuals," he said.

Their routine for the flu was conventional. "You take some Pedialyte, drink some Sprite, eat crackers and soup and in a few days it's better," he said.

Mr. Holland was due to leave on a planned trip Friday with clients to Kansas. He hesitated about leaving his wife. He took her temperature that morning. She still had a fever, but it was lower. She seemed to be recovering. "Normally you lay around for a few days," he said.

Ms. Holland, feeling better, urged him to go, he recalled. Still unsure, he checked with her one last time before leaving Friday morning.

The race home

On Friday night, Ms. Holland's fever spiked. She was nauseated and had diarrhea. Around 11 p.m., family members took her to the emergency room at Texas Health Southwest, a hospital in Fort Worth. She was admitted into the intensive-care unit.

Mr. Holland frantically searched the quickest way home. His boss drove him early Saturday to the airport, where Mr. Holland hoped to catch a 6:05 a.m. flight home. They arrived at 5:45 a.m., too late to board.

The next flight wasn't until that afternoon. The two men returned to the car and sped toward Fort Worth, Mr. Holland said, stopping only for gas.

The Hollands were high-school sweethearts. They dated for seven years while attending different colleges before getting married in July 2004.

Ms. Holland was a reader. "It was just book after book after book," her husband said. "It was God, her family and reading, basically in that order." She shared that passion with her students at Bose Ikard Elementary School, boys and girls she hugged and called her babies.

"She always said that's probably the only hug some of those kids will get that day," Mr. Holland said.

Arriving at the hospital around midday on Saturday, Mr. Holland went to his wife's bedside and told her he loved her. She said she loved him, too.

Doctors had hooked her up to equipment to help her breathe, Mr. Holland said, and gave her medication to help her rest.

On Saturday night, after blood tests showed she had sepsis, an extreme complication of infections, she was put on dialysis, Mr. Holland said. He and other family members rubbed her hands and feet to warm them. Her circulation, he said, "was going by the wayside."

Doctors told the family that Ms. Holland's recovery was looking unlikely. On Sunday morning, Mr. Holland called his mother to bring the couple's children.

Ms. Holland opened her eyes to look at her young boy and girl. "She'd hold them open as long as she could, then she'd close them, then open them again a little bit," he said. "That was her way of telling them goodbye."

She died soon after, on Feb. 4, six days after coming home from school with a scratchy throat.

Comment: Misinformation and downright deception abound with regard to flu vaccines.

- Identifying and treating sepsis: The real reason why some die of flu

- It's "flu-shot season" again: What you may not know about the flu shot

- Eighteen Reasons Why You Should NOT Vaccinate Your Children Against The Flu This Season

- The Health & Wellness Show: Flu Season: Don't believe the hype

- Roche's Tamiflu Not Proven to Cut Flu Complications

- Q & A on the enormous lies of vaccination

and some safe, natural alternatives