That's very true.

In a mild way, the quote also illustrates itself since it is so often attributed wrongly; perhaps most often to Mark Twain but also to other humorists - Will Rogers, Artemus Ward, Kin Hubbard - as well as to inventor Charles Kettering, pianist Eubie Blake, baseball player Yogi Berra, and more ("Bloopers: Quote didn't really originate with Will Rogers").

Such mis-attributions of insightful sayings are perhaps the rule rather than any exception; sociologist Robert Merton even wrote a whole book (On the Shoulders of Giants, Free Press 1965 & several later editions) about mis-attributions over many centuries of the modest acknowledgment that "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants".

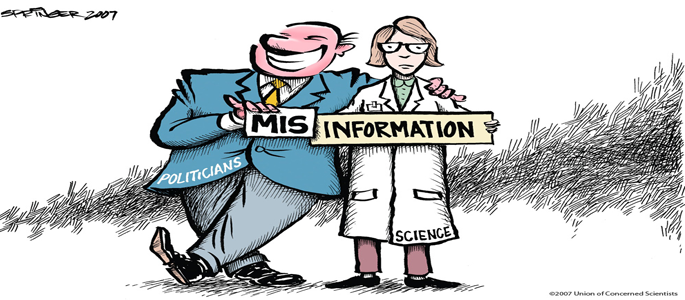

No great harm comes from mis-attributing words of wisdom. Great harm is being done nowadays, however, by accepting much widely believed and supposedly scientific medical knowledge; for example about hypertension, cholesterol, prescription drugs, and more (see works listed in What's Wrong with Present-Day Medicine).

The trouble is that "science" was so spectacularly successful in elucidating so much about the natural world and contributing to so many useful technologies that it has come to be regarded as virtually infallible.

Historians and other specialist observers of scientific activity - philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, various others - of course know that science, no less than all other human activities, is inherently and unavoidably fallible.

Until the middle of the 20th century, science was pretty much an academic vocation not venturing very much outside the ivory towers. Consequently and fortunately, the innumerable things on which science went wrong in past decades and centuries did no significant damage to society as a whole; the errors mattered only within science and were corrected as time went by. Nowadays, however, science has come to pervade much of everyday life through its influences on industry, medicine, and official policies on much of what governments are concerned with: agriculture, public health, environmental matters, technologies of transport and of warfare, and so on. Official regulations deal with what is permitted to be in water and in the air and in innumerable man-made products; propellants in spray cans and refrigerants in cooling machinery have been banned, globally, because science (primarily chemists) persuaded the world that those substances were reaching the upper atmosphere and destroying the natural "layer" of ozone that absorbs some of the ultraviolet radiation from the sun, thereby protecting us from damage to eyes and skin. For the last three decades, science (primarily physicists) has convinced the world that human generation of carbon dioxide is warming the planet and causing irreversible climate change.

So when science goes wrong nowadays, that can do untold harm to national economies, and to whole populations of people if the matter has to do with health.

Yet science remains as fallible as it ever was, because it continues to be done by human beings. The popular illusion that science is objective and safeguarded from error by the scientific method is simply that, an illusion: the scientific method describes how science perhaps ought to be done, but how it is done depends on the human beings doing it, none of whom never make mistakes.

When I wrote that "science persuaded the world" or "convinced the world", of course it was not science that did that, because science cannot speak for itself. Rather, the apparent "scientific consensus" at any given time is generally taken a priori as "what science says". But it is rare that any scientific consensus represents what all pertinent experts think; and consensus is appealed to only when there is controversy, as Michael Crichton pointed out so cogently: "the claim of consensus has been the first refuge of scoundrels[,] ... invoked only in situations where the science is not solid enough. Nobody says the consensus of scientists agrees that E=mc2. Nobody says the consensus is that the sun is 93 million miles away. It would never occur to anyone to speak that way".

Yet the scientific consensus represents contemporary views incorporated in textbooks and disseminated by science writers and the mass media. Attempting to argue publicly against it on any particular topic encounters the pervasive acceptance of the scientific consensus as reliably trustworthy. What reason could there be to question "what science says"? There seems no incentive for anyone to undertake the formidable task of seeking out and evaluating the actual evidence for oneself.

Here is where real damage follows from what everyone knows that just happens not to be so. It is not so that a scientific consensus is the same as "what science says", in other words what the available evidence is, let alone what it implies. On any number of issues, there are scientific experts who recognize flaws in the consensus and dissent from it. That dissent is not usually mentioned by the popular media, however; and if it should be mentioned then it is typically described as misguided, mistaken, "denialism".

Examples are legion. Strong evidence and expert voices dissent from the scientific consensus on many matters that the popular media regard as settled: that the universe began with a Big Bang about 13 billion years ago; that anti-depressant drugs work specifically and selectively against depression; that human beings (the "Clovis" people) first settled the Americas about 13,000 years ago by crossing the Bering Strait; that the dinosaurs were brought to an end by the impact of a giant asteroid; that claims of nuclear fusion at ordinary temperatures ("cold fusion") have been decisively disproved; that Alzheimer's disease is caused by the build-up of plaques of amyloid protein; and more. Details are offered in my book, Dogmatism in Science and Medicine: How Dominant Theories Monopolize Research and Stifle the Search for Truth (McFarland, 2012). That book also documents the widespread informed dissent from the views that human-generated carbon dioxide is the prime cause of global warming and climate change, and that HIV is not the cause of AIDS (for which see the compendium of evidence and sources at The Case against HIV).

The popular knowledge that just isn't so is, directly, that it is safe to accept as true for all practical purposes what the scientific consensus happens to be. That mistaken knowledge can be traced, however, to knowledge that isn't so about the history of science, for that history is a very long story of the scientific consensus being wrong and later modified or replaced, quite often more than once.

Dangerous knowledge II: Wrong knowledge about the history of science

Knowledge of history among most people is rarely more than superficial; the history of science is much less known even than is general (political, social) history. Consequently, what many people believe they know about science is typically wrong and dangerously misleading.

General knowledge about history, the conventional wisdom about historical matters, depends on what society as a whole has gleaned from historians, the people who have devoted enormous time and effort to assemble and assess the available evidence about what happened in the past.

Society on the whole does not learn about history from the specialists, the primary research historians. Rather, teachers of general national and world histories in schools and colleges have assembled some sort of whole story from all the specialist bits, perforce taking on trust what the specialist cadres have concluded. The interpretations and conclusions of the primary specialists are filtered and modified by second-level scholars and teachers. So what society as a whole learns about history as a whole is a sort of third-hand impression of what the specialists have concluded.

History is a hugely demanding pursuit. Its mission is so vast that historians have increasingly had to specialize. There are specialist historians of economics, of mathematics, and of other aspects of human cultures; and there are historians who specialize in particular eras in particular places, say Victorian Britain. Written material still extant is an important resource, of course, but it cannot be taken literally, it has to be evaluated for the author's identity, and clues as to bias and ignorance. Artefacts provide clues, and various techniques from chemistry and physics help to discover dates or to test putative dates. What further makes doing history so demanding is the need to capture the spirit of a different time and place, an holistic sense of it; on top of which the historian needs a deep, authentic understanding of the particular aspect of society under scrutiny. So doing economic history, for example, calls not only for a good sense of general political history, it requires also a good understanding of the whole subject of economics itself in its various stages of development.

The history of science is a sorely neglected specialty within history. There are History Departments in colleges and universities without a specialist in the history of science - which entails also that many of the people who - at both school and college levels - teach general history or political or social or economic history, or the history of particular eras or places, have never themselves learned much about the history of science, not even as to how it impinges on their own specialty. One reason for the incongruous place - or lack of a place - for the history of science with respect to the discipline of history as a whole is the need for historians to command an authentic understanding of the particular aspect of history that is their special concern. Few if any people whose career ambition was to become historians have the needed familiarity with any science; so a considerable proportion of historians of science are people whose careers began in a science and who later turned to history.

Most of the academic research in the history of science has been carried on in separate Departments of History of Science, or Departments of History and Philosophy of Science, or Departments of History and Sociology of Science, or in the relatively new (founded within the last half a century) Departments of Science & Technology Studies (STS).

Before there were historian specialists in the history of science, some historical aspects were typically mentioned within courses in the sciences. Physicists might hear bits about Galileo, Newton, Einstein. Chemists would be introduced to thought-bites about alchemy, Priestley and oxygen, Haber and nitrogen fixation, atomic theory and the Greeks. Such anecdotes were what filtered into general knowledge about the history of science; and the resulting impressions are grossly misleading. Within science courses, the chief interest is in the contemporary state of known facts and established theories, and historical aspects are mentioned only in so far as they illustrate progress toward ever better understanding, yielding an overall sense that science has been unswervingly progressive and increasingly trustworthy. In other words, science courses judge the past in terms of what the present knows, an approach that the discipline of history recognizes as unwarranted, since the purpose of history is to understand earlier periods fully, to know about the people and events in their own terms, under their own values.

* * * * * *

How to explain that science, unlike other human ventures, has managed to get better all the time? It must be that there is some "scientific method" that ensures faithful adherence to the realities of Nature. Hence the formulaic "scientific method" taught in schools, and in college courses in the behavioral and social sciences (though not in the natural sciences).

Specialist historians of science, and philosophers and sociologists of science and scholars of Science & Technology Studies all know that science is not done by any such formulaic scientific method, and that the development of modern science owes as much to the precursors and ground-preparers as to such individual geniuses as Newton, Galileo, etc. - Newton, by the way, being so fully aware of that as to have used the modest "If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants" mentioned in my previous post (Dangerous knowledge).

* * * * * *

Modern science cannot be understood, cannot be appreciated without an authentic sense of the actual history of science. Unfortunately, for the reasons outlined above, contemporary culture is pervaded by partly ignorance and partly wrong knowledge of the history of science. In elementary schools and in high schools, and in college textbooks in the social sciences, students are mis-taught that science is characterized, defined, by use of "the scientific method". That is simply not so: see Chapter 2 in Science Is Not What You Think: How It Has Changed, Why We Can't Trust It, How It Can Be Fixed (McFarland 2017) and sources cited there. The so-called the scientific method is an invention of philosophical speculation by would-be interpreters of the successes of science; working scientists never subscribed to this fallacy, see for instance Reflections of a Physicist (P. W. Bridgman, Philosophical Library, 1955), or in 1992 the physicist David Goodstein, "I would strongly recommend this book to anyone who hasn't yet heard that the scientific method is a myth. Apparently there are still lots of those folks around" ("this book" being my Scientific Literacy and Myth of the Scientific Method).

The widespread misconception about the scientific method is compounded by the misconception that the progress of science has been owing to individual acts of genius by the people whose names are common currency - Galileo, Newton, Darwin, Einstein, etc. - whereas in reality those unquestionably outstanding individuals were not creating out of the blue but rather placing keystones, putting final touches, synthesizing; see for instance Tony Rothman's Everything's Relative: And Other Fables from Science and Technology (Wiley, 2003). The same insight is expressed in Stigler's Law, that discoveries are typically named after the last person who discovered them, not the first (S. M. Stigler, "Stigler's Law of Eponymy", Transactions of the N.Y. Academy of Science, II, 39 [1980] 147-58).

That misconception about science progressing by lauded leaps by applauded geniuses is highly damaging since it hides the crucially important lesson that the acts of genius that we praise in hindsight were vigorously, often even viciously resisted by their contemporaries, their contemporary scientific establishment and scientific consensus; see "Resistance by scientists to scientific discovery" (Bernard Barber, Science, 134 [1961] 596-602); "Prematurity and uniqueness in scientific discovery" (Gunther Stent, Scientific American, December 1972, 84-93); Prematurity in Scientific Discovery: On Resistance and Neglect (Ernest B. Hook (ed)., University of California Press, 2002).

What is perhaps most needed nowadays, as the authority of science is invoked in so many aspects of everyday affairs and official policies, is clarity that any contemporary scientific consensus is inherently and inevitably fallible; and that the scientific establishment will nevertheless defend it zealously, often unscrupulously, even when it is demonstrably wrong.

Dangerous knowledge III: Wrong knowledge about science

In the first post of this series (Dangerous knowledge) I pointed to a number of specific topics on which the contemporary scientific consensus is doubtfully in tune with the actual evidence. That disjunction is ignored or judged unimportant both by most researchers and by most observers; and that, I believe, is because the fallibility of science is not common knowledge; which in turn stems from ignorance and wrong knowledge about the history of science and, more or less as a consequence, about science itself.

The conventional wisdom regards science as a thing that is characterized by the scientific method. An earlier post (Dangerous knowledge II: Wrong knowledge about the history of science) mentioned that the scientific method is not a description of how science is done, it was thought up in philosophical speculation about how science could have been so successful, most notably in the couple of centuries following the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century.

Just as damaging as misconceptions about how science is done is the wrong knowledge that science is even a thing that can be described without explicit attention to how scientific activity has changed over time, how the character of the people doing science has changed over time, most drastically since the middle of the 20th century. What has happened since then, since World War II, affords the clearest, most direct understanding of why contemporary official pronouncements about matter of science and medicine need to be treated with similar skepticism as are official pronouncements about matters of economics, say, or politics. As I wrote earlier (Politics, science, and medicine),

In a seriously oversimplified nutshell:

The circumstances of scientific activity have changed, from about pre-WWII to nowadays, from a cottage industry of voluntarily cooperating, independent, largely disinterested ivory-tower intellectual entrepreneurs in which science was free to do its own thing, namely the unfettered seeking of truth about the natural world, to a bureaucratic corporate-industry-government behemoth in which science has been pervasively co-opted by outside interests and is not free to do its own thing because of the pervasive conflicts of interest. Influences and interests outside science now control the choices of research projects and the decisions of what to publish and what not to make public.

For a detailed discussion of these changes in scientific activity, see Chapter 1 of Science Is Not What You Think: How It Has Changed, Why We Can't Trust It, How It Can Be Fixed (McFarland 2017); less comprehensive descriptions are in Three Stages of Modern Science and The Science Bubble.

Official pronouncements are not made primarily to tell the truth for the public good. Statements from politicians are often motivated by the desire to gain favorable attention, as is widely understood. But less widely understood is that official statements from government agencies are also often motivated by the desire to gain favorable attention, to make the case for the importance of the agency (and its Director and other personnel) and the need for its budget to be considered favorably. Press releases from universities and other research institutions have the same ambition. And anything from commercial enterprises is purely self-interested, of course.

The stark corollary is that no commercial or governmental entity, nor any sizable not-for-profit entity, is devoted primarily to the public good and the objective truth. Organizations with the most laudable aims, Public Citizen, say, or the American Heart Association, etc. etc. etc., are admittedly devoted to doing good things, to serving the public good, but it is according to their own particular definition of the public good, which may not be at all the same as others' beliefs about what is best for the public, for society as a whole.

Altogether, a useful generalization is that all corporate entities, private or governmental, commercial or non-profit, have a vested self-interest in the status quo, since that represents the circumstances of their raison d'être, their prestige, their support from particular groups in society or from society as a whole.

The hidden rub is that a vested interest in the status quo means defending things as they are, even when objective observers might note that those things need to be modified, superseded, abandoned. Examples from the past are legion and well known: in politics, say, the American involvement in Vietnam and innumerable analogous matters. But not so well known is that unwarranted defense of the status quo is also quite common on medical and scientific issues. The resistance to progress, the failure to correct mis-steps in science and medicine in any timely way, has been the subject of many books and innumerable articles; for selected bibliographies, see Critiques of Contemporary Science and Academe and What's Wrong with Present-Day Medicine. Note that all these critiques have been effectively ignored to the present day, the flaws and dysfunctions remain as described.

Researchers who find evidence that contradicts the status quo, the established theories, learn the hard way that such facts don't count. As noted in my above-mentioned book, science has a love-hate relationship with the facts: they are welcomed before a theory has been established, but after that only if they corroborate the theory; contradictory facts are anathema. Yet researchers never learn that unless they themselves uncover such unwanted evidence; scientists and engineers and doctors are trained to believe that their ventures are essentially evidence-based.

Contributing to the resistance against rethinking established theory is today's hothouse, overly competitive, rat-race research climate. It is no great exaggeration to say that researchers are so busy applying for grants and contracts and publishing that they have no time to think new thoughts.

Dangerous knowledge IV: The vicious cycle of wrong knowledge

Peter Duesberg, universally admired scientist, cancer researcher, and leading virologist, member of the National Academy of Sciences, recipient of a seven-year Outstanding Investigator Grant from the National Institutes of Health, was astounded when the world turned against him because he pointed to the clear fact that HIV had never been proven to cause AIDS and to the strong evidence that, indeed, no retrovirus could behave in the postulated manner.

Frederick Seitz, at one time President of the National Academy of Sciences and for some time President of Rockefeller University, became similarly non grata for pointing out that parts of an official report contradicted one another about whether human activities had been proven to be the prime cause of global warming ("A major deception on global warming", Wall Street Journal, 12 June 1996).

A group of eminent astronomers and astrophysicists (among them Halton Arp, Hermann Bondi, Amitabha Ghosh, Thomas Gold, Jayant Narlikar) had their letter pointing to flaws in Big-Bang theory rejected by Nature.

These distinguished scientists illustrate (among many other instances involving less prominent scientists) that the scientific establishment routinely refuses to acknowledge evidence that contradicts contemporary theory, even evidence proffered by previously lauded fellow members of the elite establishment.

Society's dangerous wrong knowledge about science includes the mistaken belief that science hews earnestly to evidence and that peer review - the behavior of scientists - includes considering new evidence as it comes in.

Not so. Refusal to consider disconfirming facts has been documented on a host of topics less prominent than AIDS or global warming: prescription drugs, Alzheimer's disease, extinction of the dinosaurs, mechanism of smell, human settlement of the Americas, the provenance of Earth's oil deposits, the nature of ball lightning, the evidence for cold nuclear fusion, the dangers from second-hand tobacco smoke, continental-drift theory, risks from adjuvants and preservatives in vaccines, and many more topics; see for instance Dogmatism in Science and Medicine: How Dominant Theories Monopolize Research and Stifle the Search for Truth, Jefferson (NC): McFarland 2012. And of course society's officialdom, the conventional wisdom, the mass media, all take their cue from the scientific establishment.

The virtually universal dismissal of contradictory evidence stems from the nature of contemporary science and its role in society as the supreme arbiter of knowledge, and from the fact of widespread ignorance about the history of science, as discussed in earlier posts in this series (Dangerous knowledge; Dangerous knowledge II: Wrong knowledge about the history of science; Dangerous knowledge III: Wrong knowledge about science).

The upshot is a vicious cycle. Ignorance of history makes it seem incredible that "science" would ignore evidence, so claims to that effect on any given topic are brushed aside - because it is not known that science has ignored contrary evidence routinely. But that fact can only be recognized after noting the accumulation of individual topics on which this has happened, evidence being ignored. That's the vicious cycle.

Wrong knowledge about science and the history of science impedes recognizing that evidence is being ignored in any given actual case. Thereby radical progress is nowadays being greatly hindered, and public policies are being misled by flawed interpretations enshrined by the scientific consensus. Society has succumbed to what President Eisenhower warned against (Farewell speech, 17 January 1961) :

in holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite.

The vigorous defending of established theories and the refusal to consider contradictory evidence means that once theories have been widely enough accepted, they soon become knowledge monopolies, and support for research establishes the contemporary theory as a research cartel("Science in the 21st Century: Knowledge Monopolies and Research Cartels").

The presently dysfunctional circumstances have been recognized only by two quite small groups of people:

- Observers and critics (historians, philosophers, sociologists of science, scholars of Science & Technology Studies)

- Researchers whose own experiences and interests happened to cause them to come across facts that disprove generally accepted ideas - for example Duesberg, Seitz, the astronomers cited above, etc. But these researchers only recognize the unwarranted dismissal of evidence in their own specialty, not that it is a general phenomenon (see my talk, "HIV/AIDS blunder is far from unique in the annals of science and medicine" at the 2009 Oakland Conference of Rethinking AIDS; mov file can be downloaded at http://ra2009.org/program.html, but streaming from there does not work).

"The popular illusion that science is objective and safeguarded from error by the scientific method is simply that, an illusion"

This is the only statement that I might quibble with - not because it is untrue in itself - but because of the implication that the "scientific method" could provide a reliable proof to human error, if it was used faithfully. The "scientific method" is inherently flawed. By creating a hypothesis, then creating a way to test it, one is limiting what can be known to what is already believed to be true. This exercise in confirmation bias that is euphemistically called science keeps the research process comfortably within the bounds that are comfortable for existing power structures. What would happen, for example, if unbiased medical research were to discover that homeopathy provided more reliable support for healing than typical allopathic methods? What would that do to allopathic medical philosophy and the massive institutional, investment, and insurance entities that have been built up around it? They'd all be stood on their heads, because homeopathy is based on a completely different model of the world. There's a proverbial snowball's chance in hell that there will ever be unbiased observation of homeopathic methods in the "scientific community", let alone the development of a hypothesis to be tested. So much for the vaunted "scientific method."

"Within science courses, the chief interest is in the contemporary state of known facts and established theories, and historical aspects are mentioned only in so far as they illustrate progress toward ever better understanding, yielding an overall sense that science has been unswervingly progressive and increasingly trustworthy."

And the practitioners of science-based activities have had their egos so thoroughly pickled in this false picture that they completely identify with this myth of everlasting scientific trustworthiness. Using the medical world as an example again, just imply, by asking a few questions, that you don't completely trust standard medical dogma when you go to your next doctor's appointment. It won't take much to see the friendly demeanor change to barely-controlled irritability.