"In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule."

-Friedrich Nietzsche

"I want to understand how a normal brain becomes conservative," my professor said. "That is the thing that most puzzles me." At the time (I was in my early twenties) I completely agreed*. That was the question. Sometimes I would stare at a picture of G. W. Bush like Hamlet staring at a skull, pondering how any sane human could have voted for him. It just didn't make sense. Progressivism was so obviously correct that it baffled me that anyone could deviate from its basic principles. I didn't hate conservatives. I even knew one or two. I was just befuddled by them.

Most social scientists feel today about conservatives as my professor and I did then. Almost all social scientists (especially social psychologists) are socially liberal, and most of them voted for Barack Obama over Mitt Romney. To many of these scientists, conservatives are like eccentric antiquities that belong in a museum, where they can be carefully studied. Consequently, social psychology journals are littered with articles about conservatives. Many paint a Hieronymus Bosch-like picture of them as flawed, fallen creatures: rigid, dogmatic, close-minded, fearful, prejudiced, and inclined to authoritarianism. Scales that describe traits found among conservatives more than progressives have scary names such as Right Wing Authoritarianism, Social Dominance Orientation, and Benevolent Sexism, to name a few.

However, other researchers have expressed concern that this unflattering image of conservatives might be an unfortunate manifestation of bias from within the academy. Because most social psychologists are progressives, they simply take progressivism for granted, assuming that it is the right way to view the world and that, therefore, any divergence from its tenets is wrong and requires explanation. This leads to disparaging depictions of conservatives in the same way that having evangelical Christians study doubters would lead to disparaging depictions of atheists (imagine the scales: Unholy Skepticism Scale, Doubting Thomas Scale, et cetera). Scholars have begun to support this argument with research that suggests that progressives and conservatives are equally biased so long as scholars examine the right topics and targets. In fact, in an upcoming meta-analysis (a study that combines all effects from other studies), Dr. Peter Ditto and his colleagues found no statistically significant difference between progressives and conservatives on measures of bias.

There is reason to believe that Dr. Ditto et al.'s meta-analysis actually underestimates progressive bias (and possibly overestimates conservative bias) because it contained only a few studies that were directly about one of the most potent sources of progressive bias: perceived victims' groups (e.g., blacks, Hispanics, Muslims, women). My colleagues and I recently wrote a manuscript that supports this speculation with a few studies, and we are conducting more as I write.

Bias

Bias is an important concept both inside and outside of academia. Despite this, it is remarkably difficult to define or to measure. And many, perhaps all, studies of it are susceptible to reasonable objections from some framework of normative reasoning or another. Nevertheless, in common discourse the term is easy enough to understand. Bias is a preference or commitment that impels a person away from impartiality. If Sally is a fervid fan of the New York Knicks and uses different criteria for assessing fouls against them than against their opponents, then we would say that she is biased.

There are many kinds of biases, and bias can penetrate the cognitive process from start to finish and anywhere between. It can lead to selective exposure, whereby people preferentially seek material that favors their preferred position, and avoid material that contradicts it; it can lead to motivated skepticism, whereby people are more critical of material that opposes their preferred position than of material that supports it; and it can lead to motivated credulity, whereby people assimilate information that supports their preferred position more easily and rapidly than information that contradicts it. Often, these biases all work together.

So, imagine Sally the average ardent progressive. She probably exposes herself chiefly to progressive magazines, news outlets, and friends; and, quite possibly, she inhabits a workplace surrounded by other progressives (selective exposure). Furthermore, when she is exposed to conservative arguments or articles, she is probably extremely critical of them. That National Review article she read this morning about abortion, for example, was insultingly obtuse and only confirmed her opinion that conservatives are cognitively challenged (motivated skepticism). Compounding this, she is equally ready to praise and absorb arguments and articles in progressive magazines (motivated credulity). Just this afternoon, for example, she read a compelling takedown of the Republican tax cuts in Mother Jones which strengthened her intuition that conservatism is an intellectual and moral dead end. (This example would work equally well with an average ardent conservative). The result is an inevitably blinkered world view.

The strength of one's bias is influenced by many factors, but, for simplicity, we can break these factors into three broad categories: clarity, accuracy concerns, and extraneous concerns. Clarity refers to how ambiguous a topic is. The more ambiguous, the lower the clarity and the higher the bias. So, the score of a basketball game has very high clarity, whereas an individual foul call may have very low clarity. Accuracy concerns refer to how desirous an individual is to know the truth. The higher the concern, on average, the lower the bias. If a fervid New York Knicks fan were also a referee in training who really wanted to get foul calls right, then she would probably have lower bias than the average impassioned fan. Last, extraneous concerns refer to any concerns (save accuracy concerns) that motivate a person toward a certain answer. Probably the most powerful of these are group affiliation and status, but there are many others (self-esteem et cetera).

At risk of simplification, we might say that bias can be represented by an equation such that extraneous concerns (E) minus (accuracy concerns (A) plus clarity (C)) equals bias: (E - (A + C) = B).

This likely explains why political bias is such a powerful and apparently ineradicable form of bias: clarity is often low and extraneous concerns are often very high. People's political identities aren't like meaningless costumes that can be donned and discarded without passion. They are crucial to the self: more like skin than fabric. Therefore, people are strongly motivated to maintain positions that allow them to remain members of their preferred political coalition. Furthermore, many important political debates are about topics that are incredibly difficult to assess and study (and therefore have low clarity). What is the optimal top marginal tax rate? What is the best criminal justice policy? Will a million dollars make the local school better? This does not mean that there aren't answers to these questions; just that the answers aren't at all clear and allow plenty of space for bias to creep in.

If we want to understand the political biases people might have, we must understand their political commitments, and, even more so, we must understand their sacred values. Sacred values are strongly held values that one treats as inviolable. Opposition to abortion, for example, is a sacred value to many conservatives. They would not be willing to trade it for a less important value- say, tax cuts - and, in fact, would regard the suggested trade as reprehensible. We can imagine moral/political commitments on a continuum from "not important" to "sacred" (see table below). The more sacred the value, the more crucial to one's political identity it is.

Progressives seem to adhere to a sacred narrative about victims' groups which goes something like this:

Many groups have been abused, exploited, and oppressed by powerful European (white) men. These groups still suffer from this legacy. And society, despite modest improvements, is still sexist and racist. Although many people proclaim their dedication to equality, they are often prejudiced, sometimes in subtle ways. Victims' groups don't do as well in society as privileged groups because society has set the rules against them and because many members of the privileged purposefully harass, abuse, and discriminate against them. Although many ignore or perpetuate a system of exploitation, there are some people who have realized how heinous and oppressive society can be and who are fighting back against it. If more people come to think the way they do, if more people study racism and sexism, if more people join movements and denounce all forms of discrimination, then the world will become a better place. Those who disagree with this are part of the problem. Even if they mean well, they are part of the system and will only hinder progress and abet racists and sexists.Therefore, if we want to study progressive bias, this is exactly where we should look.

Equalitarianism

Ben Winegard, David Geary, and I wrote a comment on a Behavioral and Brain Sciences' article about political bias in 2015, in which we forwarded what we termed the "paranoid egalitarian meliorist" (PEM) model of progressive bias. I've come to believe that the name is inevitably and uncharitably pejorative ("paranoid" sounds bad even though it is descriptively neutral), so my colleagues and I have renamed it equalitarianism; however, I still think the basic model is accurate.

According to the equalitarian model, progressives are dedicated egalitarians. They think that all individuals, all groups, all sexualities, and all sexes should be treated fairly*. They are also especially sensitive to potential threats to egalitarianism, so they adhere to the belief that all demographic groups are roughly equal on all socially valued traits, a belief we call cosmic egalitarianism. Perhaps the most common form of cosmic egalitarianism is blank slate-ism, or the belief that humans are nearly infinitely malleable, and that all important differences among them are caused by the environment, not genes. Cosmic egalitarianism serves as a protective buffer to egalitarianism because it contends two things: 1) Group disparities are caused by prejudice and discrimination (unfairness), not group differences; and 2) We absolutely should treat all groups the same because they are basically the same. Equalitarians fear that if we accept that some demographic differences are genetically caused, we might start treating groups differently from each other. For example, maybe we would encourage men to pursue STEM careers more often than women. (It is worth noting that most people who believe that there are genetically-caused demographic differences would not forward such a bad argument and are committed to treating people as individuals. However, equalitarians, as noted, are very sensitive to potential threats to egalitarianism, and they view this as a potential threat.)

If this model is correct, we would expect to find that 1) Progressives are more likely than conservatives to score high on an equalitarian measure (see end for the measure); 2) Progressives are more likely than conservatives to believe that victims' groups are treated unfairly; 3) Progressives are more likely than conservatives to evince bias against threats to cosmic egalitarianism that appear to favor privileged groups over victims' groups; and 4) That these results will be explained, at least partially, by scores on our equalitarian measure. In a series of several studies, we found exactly these results.

In Study 1, for example, we found that progressives thought many demographic groups (blacks, Hispanics, Muslims, and women) were treated more unfairly than did conservatives. And these results were partially explained (the technical term is "partially mediated") by scores on our equalitarian measure. In Study 2, we found that progressives were more likely than conservatives to think that a cop who shot a black person who was discovered to be unarmed was more blameworthy. Similarly, progressives thought that a test in which men performed better than women (but that had high predictive validity) was more unfair than did conservatives. And, once again, these results were partially explained by equalitarianism.

So far, these results suggest that progressives are more sensitive to threats to egalitarianism and believe that certain demographic groups are treated unfairly by society. But they don't suggest bias. In fact, it could be that progressives are correct, and that conservatives are biased. In our next two studies, therefore, we tried to detect bias. Before presenting those results, however, it is worth discussing how difficult it is to study bias.

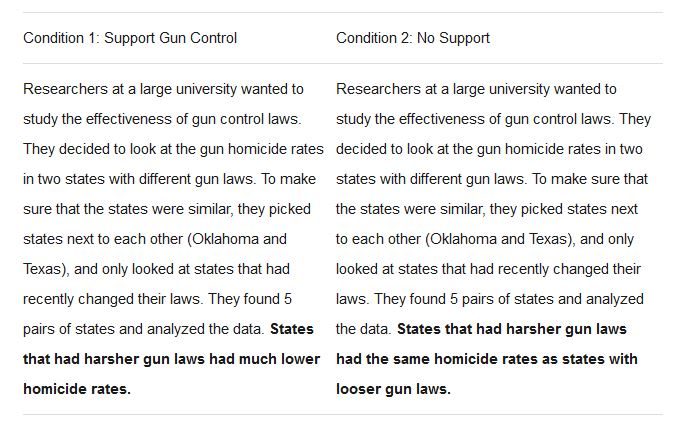

Most bias studies rely on something called the principle of invariance: decision-irrelevant information (extraneous information) should not affect judgments; therefore, any judgment that is affected by extraneous information is biased. Abstruse enough. The basic idea is this. Suppose I give groups of people a description of research methods, but in one description the results support gun control and in the other, they do not. Then I ask them to assess the quality of the methods. The rating, according to this line of thought, should be the same because the quality of the methods is independent of the results. (See the table below for an example. The bold phrasing is changed across conditions but everything else is the same.)

So, suppose progressives rate the methods in Condition 1 as more sound than in Condition 2: We would call that bias. However, I want to suggest that things aren't so simple, and concede that it is almost impossible to isolate bias in the lab. A Bayesian might reasonably argue that the results of an experiment should cause a rational person to update her assessments of the methods. My colleagues and I called this the "proof of the recipe is in the eating" (PRE) principle. If you have what appears to be a delectable recipe, but the resulting food is insipid, it is not irrational to reassess the recipe. Of course, maybe you just botched the cooking. But, maybe the recipe is actually bad. The same applies to the gun control examples. If you are convinced that gun control works, but somebody shows you that it doesn't, it isn't irrational to suspect that her methods were flawed.

All researchers can do is concede this point and try their best to isolate bias by using rigorous, but inevitably flawed, methods. Which is exactly what we did in Studies 3 and 4.

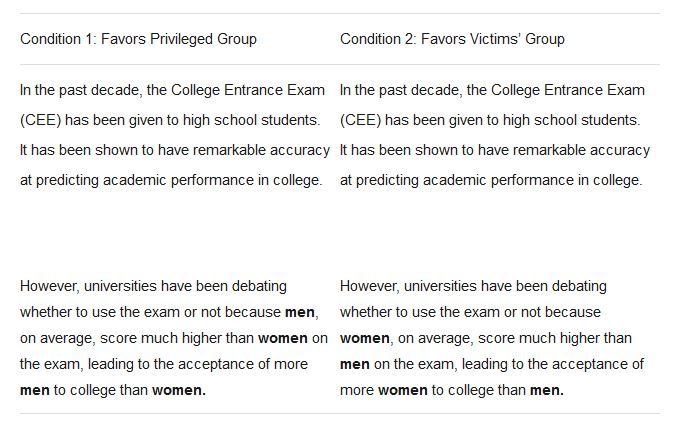

In Study 3, we described an entrance exam that colleges were considering using, but which favored either men or women (see below).

We then asked participants to rate the exam's fairness, sexism, and asked how much it should be used (we turned this into one item, called "test acceptance"). As predicted, progressives were significantly less likely to accept the test when men outperform women than when women outperform men. Also, as predicted, but probably surprising to many progressives, conservatives did not differ in their responses in either condition; in other words, conservatives were completely fair, and progressives were biased (see figure below). Also, as with the other results, these results were partially explained by equalitarian scores.

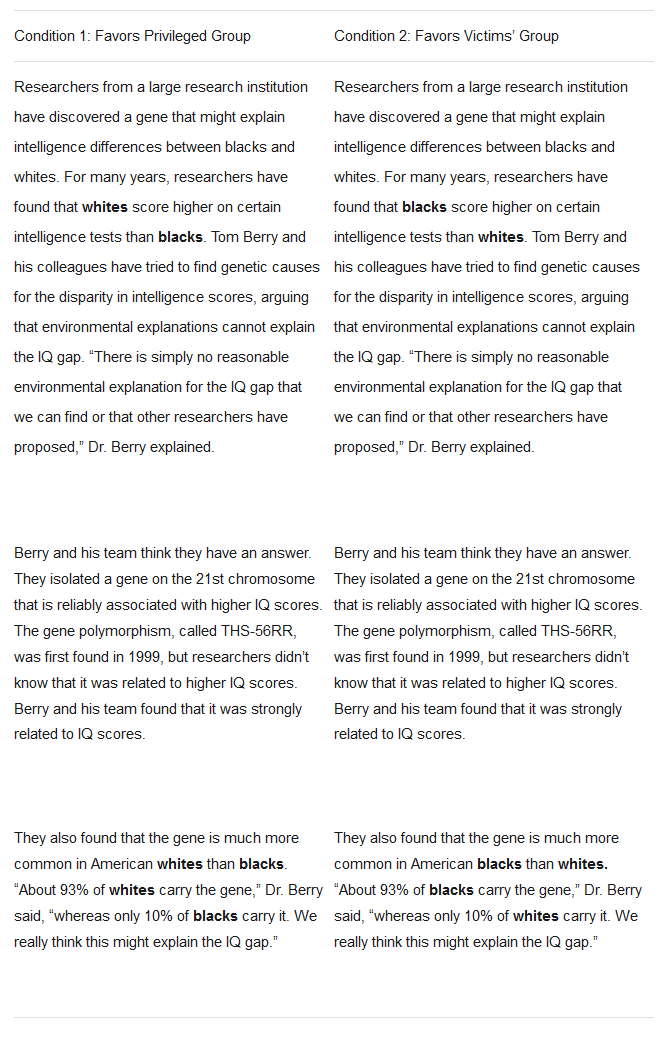

In Study 4, we used the same basic methods, but examined a different scenario: potential demographic differences on IQ test scores. Again, we matched the conditions save for the group that was said to outperform the other (black versus white; see below). We told our participants this was an article in the New York Times.

We next asked participants a number of questions about the argument such as "How credible is Dr. Berry's argument,?" "How logical is Dr. Berry's argument,?" and again combined them into one score called "argument credibility". As with Study 3, progressives were significantly less likely to evaluate the argument as credible when it favored a privileged group (whites) than when it favored a victims' group (blacks; see below). And conservatives again evinced no statistically significant bias. (They were slightly biased against the privileged group, but the result was not significant). These results were also partially explained by scores on our equalitarian measure.

Taken together, these studies provide strong support for our equalitarian model of progressive bias. It also has strong prima facie validity because it would explain why so many otherwise intelligent progressive become so irrational when discussing identity issues. To take just one example, many progressives unceasingly misrepresented and excoriated James Damore's "Google Memo" in a truly astonishing display of dishonesty. I don't think many progressives consciously meant to misrepresent it (by calling it, for example, a "sexist screed" or an "anti-diversity memo"); I think that they are such dedicated equalitarians that they actually read a judiciously-worded memo as an attack on egalitarian principles, and pounced upon it like a lion pouncing upon an animal that threatens its cubs.

The Normal Brain is Biased

Probably all people are biased; and strong ideological commitments on either side of the spectrum heighten such pre-existing propensities. My professor should have said, "I want to understand how a biased brain becomes biased in one way and not another," because the normal brain is a prejudiced brain. For too long, the progressives who have dominated the social sciences have taken progressivism for granted and have therefore examined conservatives as though they were aliens with a perplexing and quite possibly pernicious set of ideological preferences. I am thankful that many intrepid and avant-garde scholars have begun to challenge this comforting but erroneous narrative.

In our work, we believe we have found a deep well of progressive bias, a well that we have just begun to explore. Equally importantly, we also found a source of conservative fairness which deserves more attention that it will likely receive. I am hopeful that others will continue to study this source of bias and fairness and that we will, over the course of the next decade, begin to understand both progressives and conservatives better. And we will come to recognize and appreciate that we are all human, all too human.

Bo Winegard is an essayist and a graduate student at Florida State University.

***

*I would describe myself as a pragmatic centrist these days, but I still lean more left than right.

*I am also a dedicated egalitarian and I probably share many of the biases I am studying. I don't think they are necessarily bad. This paper is descriptive, not normative. It is unfortunate when people use the results to say, "Hahahaha! Progressives are stupid." That is not our point at all. Our point is simply that progressives have biases just like conservatives, and that we should strive to understand them.

Equalitarianism Measure:

Instructions: Please answer the following questions as honestly as you can. Remember, all answers will be confidential. Use the following scale: 1- do not agree all, 4-somewhat agree, 7-agree completely (so 1 is the lowest level of agreement, and 7 is the highest.)

- The only reason there are differences between men and women is because society is sexist

- Differences between men and women in society are caused by discrimination

- Differences among ethnic groups in society are at least partially biologically caused*

- Most people are not biased and racism is not a problem anymore*

- When people assert that men and women are different because of biology, they are usually trying to justify the status quo

- People often try to conceal their racism and sexism, but they act that way anyway

- People often use biology to justify unjust policies that create inequalities

- Racism is everywhere, even though people say that they are not racist

- Sexism is everywhere, even though people say that they are not sexist

- People use scientific theories to justify inequalities between groups

- Men and women have equal abilities on all tasks (for example, mathematics, sports, creativity).

- All ethnic groups have equal abilities on all tasks (for example, mathematics, sports, creativity)

- Some differences between men and women are hardwired*

- Although things are unequal now, if we work really hard, we can make society better and more fair

- We should strive to make all groups equal in society

- We should strive to make men and women equally represented in science fields

- If we work hard enough, we can ensure that all ethnic groups have equal outcomes

- With the right policies, we will increase equality in society

The underlying assumption throughout is that there is a 'range' of 'reasonable' opinions, outside of which one is considered paranoid, facts supporting their point be damned.

The writer is one who has unknowingly bought into the false dichotomy that the only realistic analysis of government is whether we should have more (and more) of it, or whether we should have ' just a 'little bit less.'

The writer doesn't even realize the constraints s/he/it ('sheit') operates under. Sheit's a weak mezzo soprano/castrati.

Likewise,the writer I'm confident, thinks of Ron Paul or PC Roberts as foolish dreamers or a nutcases. They are neither, and see the world far better than this fool does.

R.C.