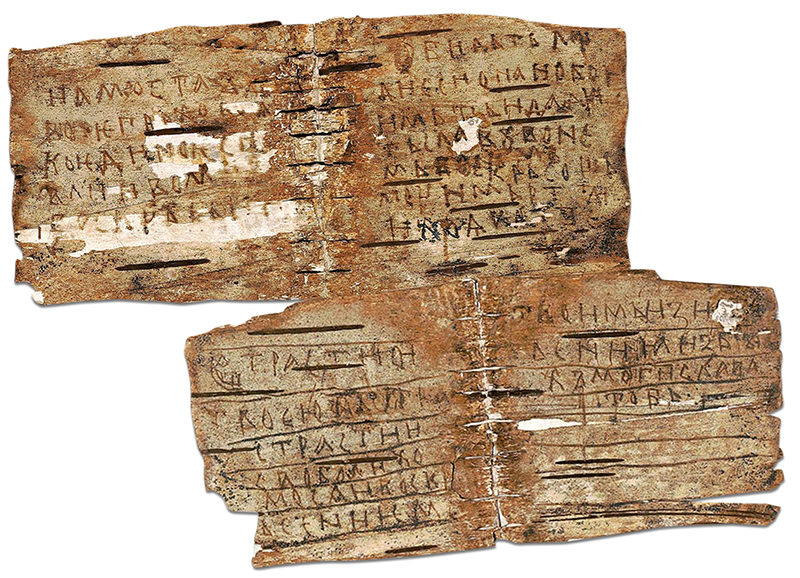

What is it? It's a bag full of notes written on birch bark. Everything from a excerpts from popular novel about Alexander the Great to the writings of the Holy Fathers to practical advice about treating common ailments-it's all there. It turns out that these birch notes aren't some fiction invented by the author. They are a historical reality. More than that, they are a kind of Rosetta Stone for Medieval Rus.

I use the term Rosetta Stone loosely here, to mean a key to a cypher. In 1951, an archaeological expedition in Novgorod found a treasure trove of these birch notes, and they became a historical sensation. They completely changed the historical thinking surrounding the everyday life of medieval Russians. (This post is adapted from an original Russian post in Foma magazine)

Notes on Everyday Life

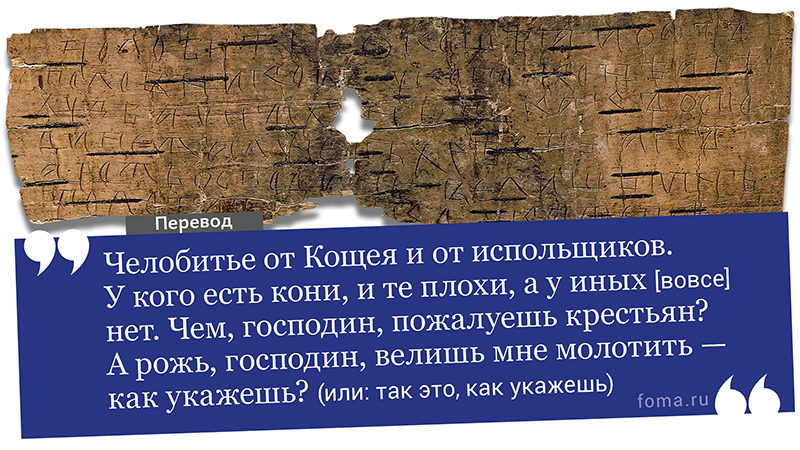

Until this expedition, most historical knowledge concerning medieval Russians came from reading the Chronicles or juridical texts. Clearly, these aren't very good at describing daily life, because they deal with "great men"-princes, nobility, clergy. But what about common people living their daily lives in the middle ages? What about the city dwellers, the peasants, the merchants, the artisans? All information about them had to be extrapolated from juridical texts; however, those deal not with concrete individuals, but social functions.

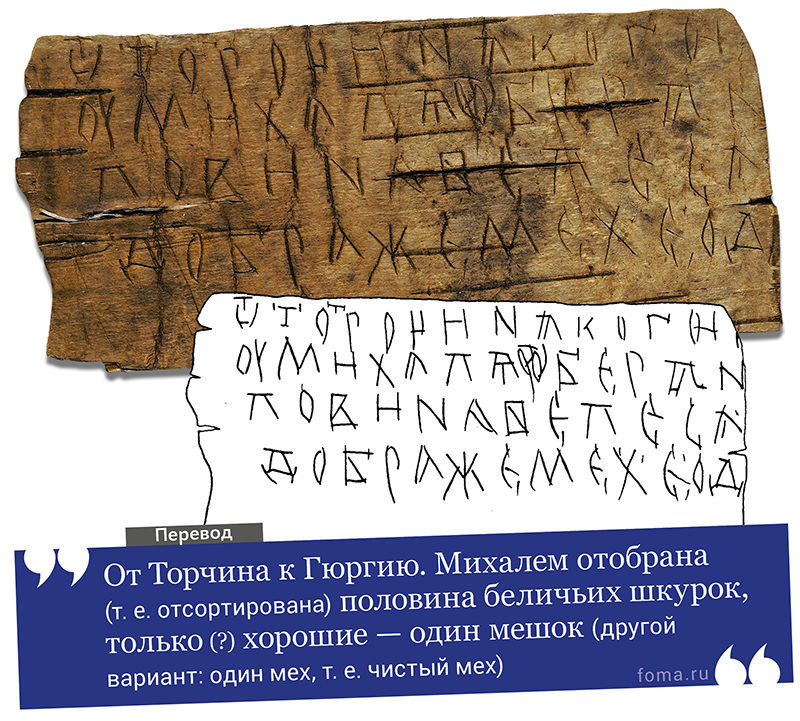

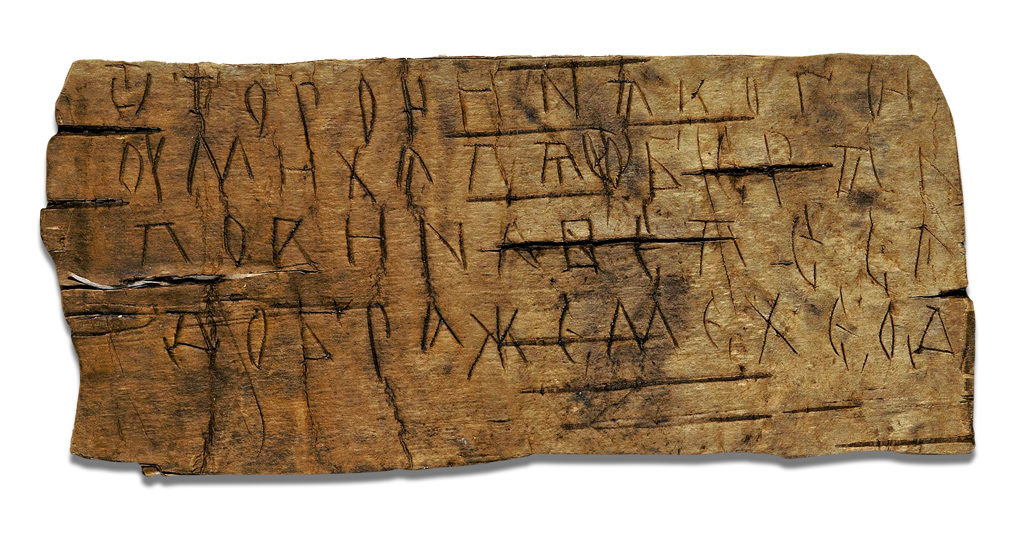

The birch notes opened a window into the actual everyday lives of the "not so great" men and women. First of all, these are extremely practical items. When a medieval Russian took up a stylus to write on a bit of birch bark, he did it because of practical necessity. For example, a merchant is traveling, and he decides to write a letter to his family. Or an artisan decides to write a formal complaint against a customer.

An interesting conundrum arises for the historian, however. As a rule, people used personal names in these notes. We find nothing about their social status. For example, someone named Miliata writes to his brother. At first, it's unclear who he is. Only contextually can a historian figure out that he's a merchant. Or when someone named Miroslav writes to Olisei Grechin, it's not immediately apparent that the first is a nobleman and the second a lawyer. But these difficulties aside, now the life of medieval Rus comes to life in vivid color and great detail.

Interestingly, in Scandinavian countries of the same time period, people wrote on wooden boards, not birch. In Rus, it was mostly a matter of tradition. Literacy spread widely after the acceptance of Christian faith and culture. The Christian tradition was preserved and disseminated in books of parchment, and in some sense, birch bark looks and feels like parchment. As for the Scandinavians, their Runic system of writing came before their acceptance of Christianity, and for many centuries they already had a tradition of etching out runes on wooden boards.

The School of Yaroslav the Wise

He gathered from the priests and the elders three hundred children and dedicated them to the study of books."Interestingly, this school made it into Scandinavian epic poetry. In the Saga of Olaf Tryggvason, the main character actually visits the school when he comes to see Yaroslav. So these three hundred children learned to read and write and became the educated elite of Novgorodian society. They formed a social foundation for the spread of literacy. They taught their own friends and, eventually, their children, and soon literacy was widespread.

Garbage dumps?

More than that, merchants immediately recognized the usefulness of literacy. Before Rus's baptism, they drew accounts by drawing pictures, not using words. These birch notes became so universal, that people just started throwing them out like garbage after they were finished.

The paradox is that this is exactly why the notes were preserved to this day. Books that were carefully protected often were destroyed in fires (which happened fairly regularly). But those items they just threw out were trampled into the dirt, and in Novgorod the soil preserves organic material very well.

This interesting fact allowed historians to find the places where Novgorodians set up their garbage dumps. It was wherever they found a large concentration of birch bark notes.

Sometimes these birch notes were mailed great distances. For example, five letters have been found of a certain merchant named Luke to his father. In one, he writes that he is traveling from the North, and he complains that in the North, they sold squirrel furs at exorbitant prices, so he didn't buy any. In another letter, he wrote from the region of the Dniepr River where he was sitting and waiting for a grechnik. That word technically refers to buckwheat, but in the local slang, it meant a Greek caravan from Byzantium (Grek is "Greek" in Russian).

Here's yet another example. A son writes to his mother, "Come here, either to Smolensk or Kiev, because bread is cheap here."

The Boy Onphim

A famous example of birch notes from that time is a boy's drawing where he depicts himself as St. George killing the dragon. Some say that this note is an actual page from a school notebook, meaning that even in the 11-12th century, there were already textbooks used in schools. In fact, it's clear that sometimes birch notes were sewn together to make notebooks even at the beginning of their appearance.

For example, there's an example of a small booklet of sewn together birch notes that contain the evening prayers. On the flip side, books of magic from the Greeks or the Copts were very popular at that time, and you find many of them still preserved. The most popular is called the "Legend of Sisinius," which is basically a book of spells to protect a mother and her newborn child from evil spirits.

Onphim actually had many notes preserved. There's a particularly funny one where he begins to write the text of a prayer, but in the middle of a word, he suddenly begins to write down the alphabet. It comes out something like this: "For He is greatly-b-c-d-e."

The Fate of the Monastery's Cow

Another interesting one dating to the 13th century is a long list of sins. Either it was a preparation for confession, or a "cheat sheet" for the priest's Sunday sermon. None of these notes are scholarly in nature. No theological self-realization is present here. This is all the practical daily necessities of a priest's life.

There's one fascinating example where we find the same handwriting in a fragment of a church calendar and a letter written from Liudslav to Khoten. No, the priest's name wasn't Liudslav. It's likely that Liudslav was illiterate and came to the priest to ask him to transcribe a personal letter for him. This also shows that the clergy in Novgorod were not isolated from the rest of the populace. They lived side-by-side with their charges and their way of thinking influenced the writing style even in secular notes.

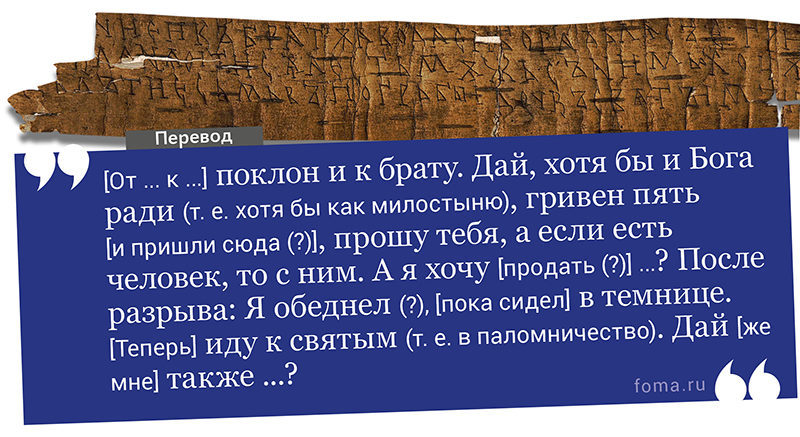

For example, many letters from that time begin with the word "I bow to you," and end with "I greet you with a kiss." The similarities to St. Paul's epistles are clear (Romans 16:16), and this tradition clearly originated in the ecclesiastical sphere.

One of the more interesting collection of notes comes from the place where a woman's monastery stood in the 12th century. It was built right in the middle of the city, in no way separated from the houses and yards of the surrounding merchants and boyars. Some of the notes found here were clearly written by nuns:

As for the three bits of cloth for the head covering, please send them over quickly."In this part of the city, mentions of God in everyday speech are also widespread. Instead of saying "Of course," people would say, "For God's sake." A common warning was "fear God." It's entirely possible that the locals started speaking like this because they were so close to the monastery.

"Can you find out if Matthew is in the monastery?" (in context, it seems Matthew is the priest)

"Is St. Barbara's heifer healthy?"

We also find an interesting fact about the clergy of the time. They didn't see themselves as a separate social class at all. For example, we already mentioned a certain Olisei Grechin. He was a fascinating character. On the one hand, he was a priest, but he was also an artist and an iconographer. But that didn't stop him from also being a central figure in the city's government. And his father was a boyar, not a priest.

Here's another interesting example from the early 15th century. It's a letter to Archbishop Simeon asking for a local deacon, Alexander, to be made priest.

"All the inhabitants of the Rzhevsk uezd in the region of Oshevsk, from the least to the greatest, bow their heads to Vladyka Simeon. We beg that Deacon Alexander be made priest, for his father and his grandfather sang before the holy Mother of God in Oshev."In other words, this was a local example of a "clergy dynasty."

The influence of Christianity was everywhere felt. When people said "For God's sake" or "fear God," these were not simply figures of speech. At the same time, the old pagan mindset persisted for a long time. For example, one of the notes has this threat: "If you don't do what I asked you about, I will consign you to the Mother of God, to whom you swore an oath." In other words, on the one hand this person is appealing to ecclesiastical authority, but on the other hand, he uses the language of cursing, typical of a pagan.

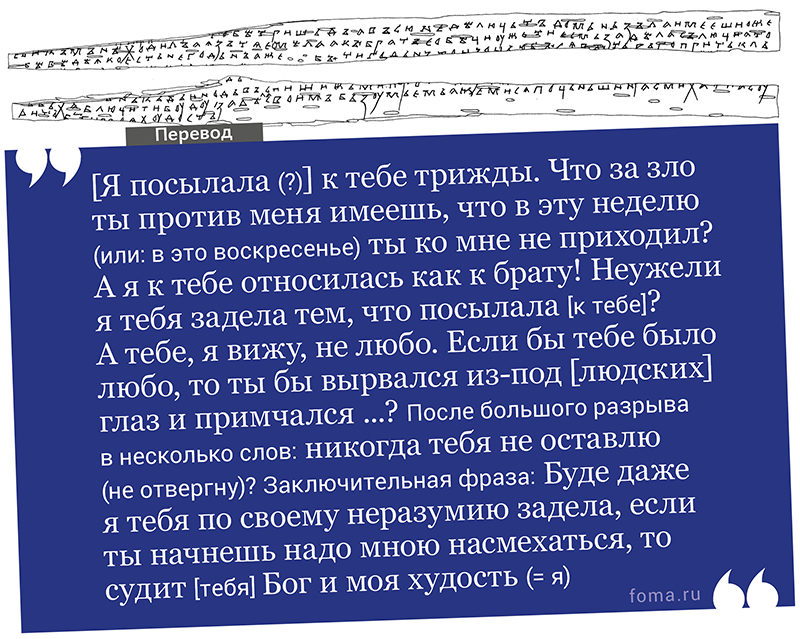

Another example is a letter from the 11th century written by a young woman to the man she loved. She rebuked him in a way that sounds completely understandable to modern ears: "Did I offend you when I asked you to come to me?" The rest of the letter (shown in the photo below goes like this:

I sent for you three times. Why are you so angry with me that you didn't come to me on Sunday? I've only ever treated you like a brother! Did I offend you when I asked you to come to me? It seems you don't love me. If you loved me, you would tear yourself from the eyes of others and run to me...I will never reject you. Even if I offended you without knowing it, if you begin to mock me, may God and my unworthiness judge you."That expression "my unworthiness" is a literary expression that comes from a well-known Greek source. (Women were as educated as men at that time, in other words).

Sadly, this letter was torn by the recipient, tied together into a knot and thrown off a bridge.

The persistence of a pagan mindset was also seen in widespread spells that were half-incantations, half prayers, spoken against all manner of evils. Here's one that was supposed to guard against the flu:

"Thrice-nine (an expression reminiscent more of folk tales than of prayers -NK) angels, thrice-nine archangels, deliver the servant of God Micah from the shakes by the prayers of the Holy Theotokos."All this is extremely interesting in our time, when the middle ages, a time of profound faith, are still routinely ridiculed as a "Dark Age." In actual fact, the coming of Christianity meant the coming of literacy and culture. It's something to think about as more and more people lambaste Christianity as a source of darkness and ignorance, when it has always been a source of education, illumination, and wisdom.

Reader Comments

To be such a stupid people in this year of 2017 is simply over-the-top mindboggling uncomprehensibly STUPID.

SS (StupidSpecies) The ONE and ONLY.

Aho

I love this one If you loved me, you would tear yourself from the eyes of others and run to me... That had to be saved