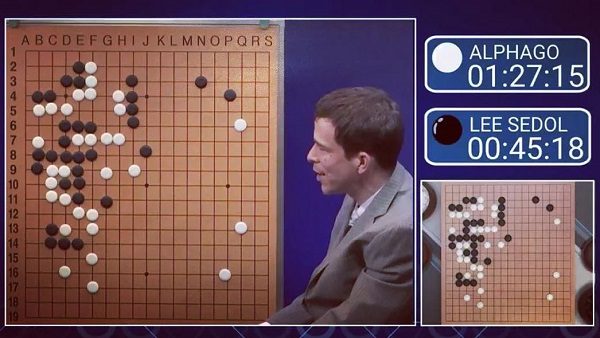

© ErikbensonMatch 3 of AlphaGo vs Lee Sedol in March 2016.

Google's artificial intelligence group, DeepMind, has unveiled the latest incarnation of its Go-playing program, AlphaGo - an AI so powerful that it derived thousands of years of human knowledge of the game before inventing better moves of its own, all in the space of three days.

Named AlphaGo Zero, the AI program has been hailed as a major advance because it mastered the ancient Chinese board game from scratch, and with no human help beyond being told the rules. In games against the 2015 version, which famously beat Lee Sedol, the South Korean grandmaster, in the following year, AlphaGo Zero won 100 to 0.

The feat marks a milestone on the road to general-purpose AIs that can do more than thrash humans at board games. Because AlphaGo Zero learns on its own from a blank slate, its talents can now be turned to a host of real-world problems.

At DeepMind, which is based in London, AlphaGo Zero is working out how proteins fold, a massive scientific challenge that could give drug discovery a sorely needed shot in the arm.

"For us, AlphaGo wasn't just about winning the game of Go," said Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind and a researcher on the team. "It was also a big step for us towards building these general-purpose algorithms." Most AIs are described as "narrow" because they perform only a single task, such as translating languages or recognising faces, but general-purpose AIs could potentially outperform humans at many different tasks. In the next decade, Hassabis believes that AlphaGo's descendants will work alongside humans as scientific and medical experts.

Previous versions of AlphaGo learned their moves by training on thousands of games played by strong human amateurs and professionals. AlphaGo Zero had no such help. Instead, it learned purely by playing itself millions of times over. It began by placing stones on the Go board at random but swiftly improved as it discovered winning strategies.

"It's more powerful than previous approaches because by not using human data, or human expertise in any fashion, we've removed the constraints of human knowledge and it is able to create knowledge itself," said David Silver, AlphaGo's lead researcher.

The program amasses its skill through a procedure called reinforcement learning. It is the same method by which balance on the one hand, and scuffed knees on the other, help humans master the art of bike riding. When AlphaGo Zero plays a good move, it is more likely to be rewarded with a win. When it makes a bad move, it edges closer to a loss.

At the heart of the program is a group of software "neurons" that are connected together to form an artificial neural network. For each turn of the game, the network looks at the positions of the pieces on the Go board and calculates which moves might be made next and probability of them leading to a win. After each game, it updates its neural network, making it stronger player for the next bout. Though far better than previous versions, AlphaGo Zero is a simpler program and mastered the game faster despite training on less data and running on a smaller computer. Given more time, it could have learned the rules for itself too, Silver said.

Writing in the journal Nature, the researchers describe how AlphaGo Zero started off terribly, progressed to the level of a naive amateur, and ultimately deployed highly strategic moves used by grandmasters, all in a matter of days. It discovered one common play, called a

joseki, in the first 10 hours. Other moves, with names such as "small avalanche" and "knight's move pincer" soon followed. After three days, the program had discovered brand new moves that human experts are now studying. Intriguingly, the program grasped some advanced moves long before it discovered simpler ones, such as a pattern called a ladder that human Go players tend to grasp early on.

"It discovers some best plays, josekis, and then it goes beyond those plays and finds something even better," said Hassabis. "You can see it rediscovering thousands of years of human knowledge."

Eleni Vasilaki, professor of computational neuroscience at Sheffield University, said it was an impressive feat. "This may very well imply that by not involving a human expert in its training, AlphaGo discovers better moves that surpass human intelligence on this specific game," she said.

But she pointed out that, while computers are beating humans at games that involve complex calculations and precision, they are far from even matching humans at other tasks. "AI fails in tasks that are surprisingly easy for humans," she said. "Just look at the performance of a humanoid robot in everyday tasks such as walking, running and kicking a ball."

Tom Mitchell, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh called AlphaGo Zero an "outstanding engineering accomplishment". He added: "It closes the book on whether humans are ever going to catch up with computers at Go. I guess the answer is no. But it opens a new book, which is where computers teach humans how to play Go better than they used to."

The idea was welcomed by Andy Okun, president of the American Go Association: "I don't know if morale will suffer from computers being strong, but it actually may be kind of fun to explore the game with neural-network software, since it's not winning by out-reading us, but by seeing patterns and shapes more deeply."

While AlphaGo Zero is a step towards a general-purpose AI, it can only work on problems that can be perfectly simulated in a computer, making tasks such as driving a car out of the question. AIs that match humans at a huge range of tasks are still a long way off, Hassabis said. More realistic in the next decade is the use of AI to help humans discover new drugs and materials, and crack mysteries in particle physics. "I hope that these kinds of algorithms and future versions of AlphaGo-inspired things will be routinely working with us as scientific experts and medical experts on advancing the frontier of science and medicine," Hassabis said.

Comment: More on Google's DeepMind: