Well, yes he's a corpse, but he has a good job...

Imagine you're dead. Not just dead inside. Truly pushing up daisies. An ex-parrot. There is an upside. You don't have to go to work anymore. Or perhaps the career options are just somewhat limited. You can strum a harp in heaven, roast in the Lake of Fire, or idle away the millennia in the oblivion of Limbo wondering if some other religion had the inside track. No doubt these are dissatisfactory pursuits for those who felt they had a noble, albeit mortal calling. Sure you get to rub elbows with the long dead luminaries of your field, but that gets old quickly when you point out their shocking revelations can be found in middle school textbooks and it's a bit disingenuous to discuss philosophy with deceased intellectual giants when you have hundreds of years of commentaries about them to draw from. Aristotle and Plato are probably right now itching to wring some punk, recently dead graduate student's neck. It's no wonder that historically there exists a class of phantasm that I like to think of as "the working undead". Take the 17th Century Prussian apothecary's apprentice Christopher Monig.

Christopher Monig hailed from a little town called Zerbst in the Anhalt-Wittenberg region of Germany, but left home to seek his fortune in Crossen, Silesia (basically western Poland), where he found gainful employment in the nascent 17th Century pharmaceutical industry, taking up an apprenticeship under a local apothecary. In 1659 he had the bad foresight to abruptly die and was buried in accordance with the rituals of the Lutheran Church. Usually the story ends there, but not for young Christopher. A few days after his death, he showed up for work. For many of us it's hard to get up and go to our jobs while we're alive. You're in luck. The next time you say, "I'd rather be dead than go in today," know that one can have the best of both worlds.

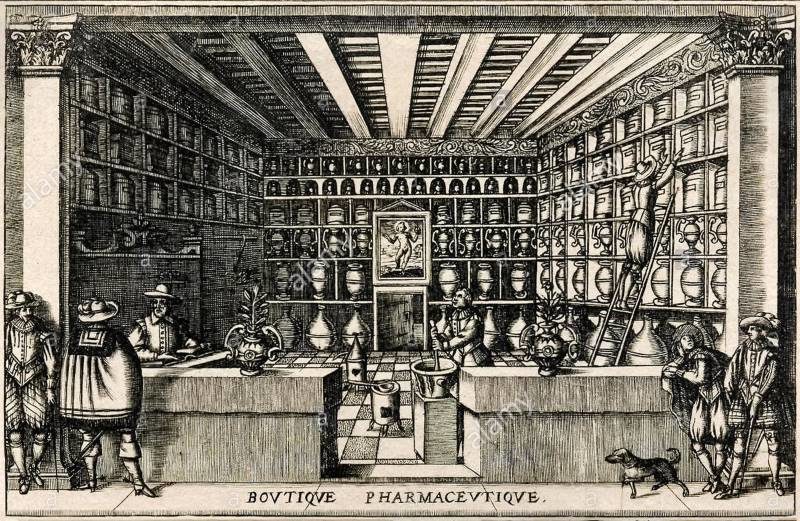

In 1659 there died at Crossen, in Silesia, an apothecary's apprentice, named Christopher Monig. Some days after they perceived a phantom in the pharmacy. Every one recognized Christopher Monig. This phantom seated itself, rose, went to the shelves, seized pots, flasks, etc., and changed their places. It examined and tasted drugs, weighed them in the scales, pounded the drugs with a noise, served the persons who presented prescriptions, received the money and placed it in the drawer. No one, however, dared to speak to it. Having, doubtless, some grudge against the master, then very seriously ill, it busied itself with giving him all sorts of annoyances. One day it took a cloak which was in the pharmacy, opened the door, and went out. It walked through the streets without looking at anyone, entered the houses of several of his acquaintances, gazed at them a moment without speaking a word, and withdrew (Assier, 1887, p269-270).In short, the recently expired Monig spent his days attending to the tasks assigned to any journeyman apothecary worth his salt. It's unclear that he was harassing his former master, sick with gout, as it was said that from his master he "would take the bills that were brought him, out of his hand, snatch away the candle sometimes, and put it behind the stove" (Sinclair, 1871, p133-134). Perhaps he thought he was alleviating the burdens of his former employer. There is no record if he brought him coffee or picked up his laundry. While Monig went about on his spectral wanderings, he ran across a familiar maid-servant near the graveyard, and this was the sole attempt he made to communicate.

He entered into some of the citizen's houses, especially such as he had formerly known, yet spoke to no one, but to a maid servant, whom he met with hard by the churchyard, whom he desired to go home and dig in a lower chamber of her master's house, where she would find an inestimable treasure. But the girl, amazed at the sight of him, swooned away; whereupon he lifted her up, but left a mark upon her in so doing, that was long visible. She fell sick in consequence of the fright, and having told what Monig had said to her, they dug up the place indicated, but found nothing but a decayed pot with hematites or bloodstone in it. (Crowe, 1848, p175-176).17th Century apothecaries were known to dabble in alchemy now and again, so while disappointment reigned at the lack of hidden horde of gold and jewels, Monig was offering, "Bloodstone" (a variety of green jasper with red hematite inclusions). Doctor of the Church, Dominican friar, and alchemical all-star Albertus Magnus(1200-1280 A.D.) referred to Bloodstone as "The Stone of Babylon" and a number of magical properties were attributed to it, including confering invisibility, rain-making, inducing solar eclipses, and the preservation of health and youth. A sort of low-rent Philosopher's Stone which would indeed have had enormous value to a budding alchemist. Some folks thought the return of Christopher Monig was a trick of the devil. There was precedent as "apothecaries seem to have been special victims of these Satanic pranks, for another appeared at Reichenbach not long before, affirming that he had poisoned several men with his drugs" (Lowell, 1904, p172-173). With so many witnesses and the persistence of this pesky phantom, it behooved local officials to take notice. Plus, with the undead crowding the job market, you might have to build a wall or something.

Elizabeth Charlotte of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1647-1723) was a Princess of Anhalt-Harzgerode by birth and was nominally in charge of the town of Cossen. She ordered an exhumation of Christopher Monig on the presumption that he was probably a vampire.

The Princess hereupon caused the young man's body to be dug up, which they found putrefied with purulent matter flowing from it [discharging pus like any self-respecting corpse] and the Master being advised to remove the young man's goods, linens, clothes, and things he left behind him when he died, out of the house. The spirit thereupon left the house, and was seen no more. And this some people now living will give their oath upon, who very well remember they saw him after his decease, and the thing being so notorious, there was instituted a Public Disputation about it in the Academy of Leipzig, by one Henry Conradus, who disputed for his Doctors degree in the University (Sinclair, 1871, p133-134).Well, at least Conradus got a dissertation out of it. "What is especially remarkable in this case is, that the apparition was visible to the external eye" (Brittan, 1856, p183-184), seen by countless witnesses, and proudly pursuing the furtherance of his career, despite the obvious disadvantages that being dead entails. It's hard to stay competitive in this world of endless internships, but if you want to stand out from the crowd, recruiters can't help but notice if your resume says "deceased". Nothing shows a serious work ethic like punching your time card post-mortem. As the author John Ruskin said, "Whether for life or death, do your own work well".

References

Assier, Adolphe d', 1828-. Posthumous Humanity: a Study of Phantoms. London: G. Redway, 1887.

Crowe, Catherine, 1800?-1876. The Night Side of Nature, or, Ghosts and Ghost Seers. London: T.C. Newby, 1848.

Lowell, James Russell, 1819-1891. The Complete Writings of James Russell Lowell. Elmwood ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1904.

Motherwell, William, 1797-1835. Poetical Works. New ed., Paisley: Gardner, 1881.

Sinclair, George, d. 1696. Satan's Invisible World Discovered. Edinburgh: T.G. Stevenson, 1871

.

Brittan, S. B. (Samuel Byron), d. 1883. "Conference at the Telegraph Office". The Spiritual Telegraph v7. New-York: Partridge & Brittan, 1856.

"Witchcraft". The North American Review v106. Boston: O. Everett, 1868.

Reader Comments