The drugs were so toxic that they changed the colour of her skin, damaged her hearing and vision, caused excruciating joint pain, triggered bouts of psychosis, left her constantly nauseous and unable to eat. At one point, she was a skeletal 70 pounds and coughing up blood daily.

Ms. Chavan lost track of how many times doctors told her family she would be better off dead. "I myself often felt that dying would be easier, too," she added.

Yet, Ms. Chavan considers herself lucky. She survived and was cured of tuberculosis - multidrug-resistant tuberculosis.

On Monday in Montreal, she told her MDR-TB ( multidrug-resistant strains) horror story to a rapt audience of the Global Health Program at McGill University.

It is a cautionary tale, one that highlights how ancient diseases such as TB are not only making a comeback but becoming more deadly, how the misuse of antibiotics is leading to dangerous resistance and how good diagnostics are essential to successful treatment.

Monday's course at McGill focused on diagnostics, so let's start there.

When she was 16 and finishing high school in Mumbai, Ms. Chavan developed a nagging cough - not an uncommon problem in a crowded, polluted city.

The problem persisted for a month, so she underwent a chest X-ray, which revealed TB.

That was a shock. In India, tuberculosis is largely an illness of the poor, who often live in overcrowded slums.

Ms. Chavan lived a comfortable middle-class life. But she did take public transit to school daily, and figures she was infected there. (TB is a bacterial infection that spreads when people cough, sneeze or spit.)

Ms. Chavan - unlike many people who cannot afford medical care - was diagnosed relatively quickly. She began a standard TB treatment - four different antibiotics daily for six months.

But it turned out she was not diagnosed well, and it took months to figure out she had MDR-TB - meaning she did not respond to isoniazid and rifampicin, two of the most powerful standard TB drugs.

That meant surgery to remove the upper lobe of her right lung, and a new drug regime, one that was more onerous and toxic, including daily injections.

The problem is that Ms. Chavan never underwent resistance testing - diagnostic tests that could identify the drugs to which her TB was resistant.

Instead, she was prescribed drugs on a hit-or-miss basis, and grew increasingly ill.

Comment: This is clearly a case of malpractice.

Madhukar Pai, director of McGill Global Health Programs, has focused on improving diagnostics, calling it the weak link in TB control.

Rapid molecular testing can result in more targeted and cheaper treatments, and lessen antibiotic resistance.

Controlling tuberculosis must be a priority, because it is the world's most deadly infectious disease, killing 1.8 million people in 2015 - more than HIV/AIDS and malaria combined.

There were an estimated 10.4 million cases of TB in 2015 (including 580,000 cases of MDR-TB), but Dr. Pai notes that only 6.1 million of those cases were officially detected and registered with TB control programs. That means 4.3 million cases were not diagnosed or officially declared.

All told, an estimated 40 per cent of TB cases go untreated and, as Ms. Chavan's case highlights, many are also mistreated. This is concerning because each person with active TB can infect 15 to 20 others annually.

Without proper diagnosis, there cannot be proper treatment.

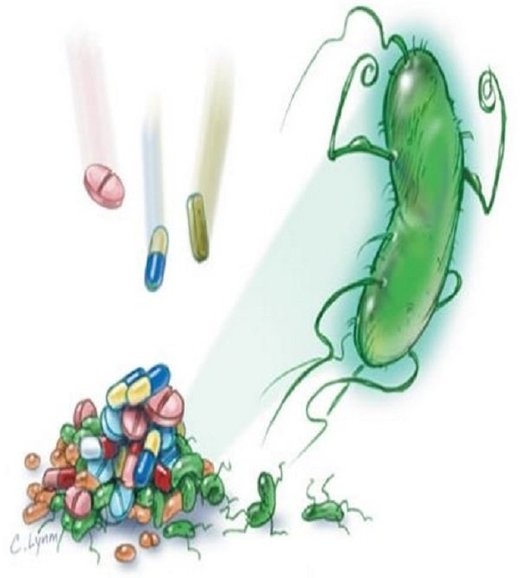

In recent decades, we have used antibiotics haphazardly and irresponsibly, and that has led to widespread antibiotic resistance.

Comment: The Health & Wellness Show: What have we done? Antibiotic resistance in the age of superbugs

MDR-TB is just one example of the risk we face from so called "superbugs" that are resistant to available antibiotics.

"The world is heading towards a post-antibiotic era in which common infections will once again kill," Margaret Chan, director-general of the World Health Organization, said last April.

"If current trends continue, sophisticated interventions, like organ transplantation, joint replacements, cancer chemotherapy and care of pre-term infants, will become more difficult or even too dangerous to undertake. This may even bring the end of modern medicine as we know it."

Comment: That may be a good thing. The entire medical system could do with a complete overhaul.

That may sound alarmist, but the reality is that the efficacy of antibiotics is deteriorating quickly.

By some estimates, if left unchecked, antibiotic resistance could lead to 10 million deaths annually by 2050, as common infections once again become everyday killers.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter