"We feel it's critical that the scientific community consider the potential hazards of all off-target mutations caused by CRISPR, including single nucleotide mutations and mutations in non-coding regions of the genome," says co-author Stephen Tsang, MD, PhD, the Laszlo T. Bito Associate Professor of Ophthalmology and associate professor of pathology and cell biology at Columbia University Medical Center and in Columbia's Institute of Genomic Medicine and the Institute of Human Nutrition.

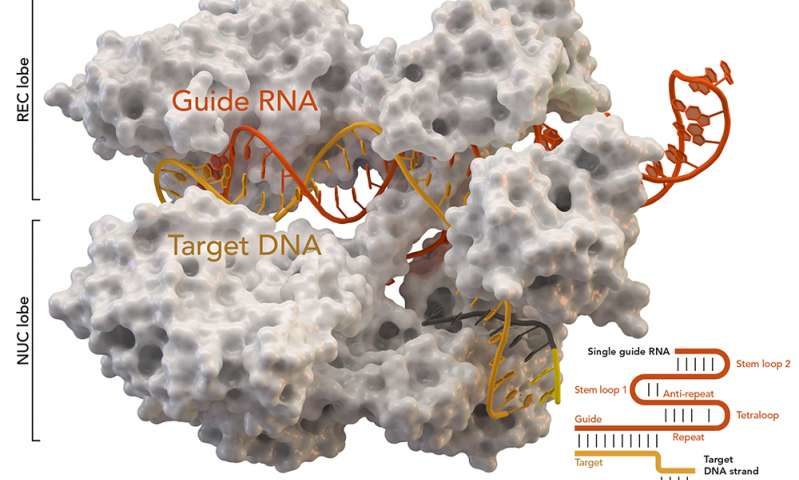

CRISPR-Cas9 editing technology—by virtue of its speed and unprecedented precision—has been a boon for scientists trying to understand the role of genes in disease. The technique has also raised hope for more powerful gene therapies that can delete or repair flawed genes, not just add new genes.

The first clinical trial to deploy CRISPR is now underway in China, and a U.S. trial is slated to start next year. But even though CRISPR can precisely target specific stretches of DNA, it sometimes hits other parts of the genome. Most studies that search for these off-target mutations use computer algorithms to identify areas most likely to be affected and then examine those areas for deletions and insertions.

"These predictive algorithms seem to do a good job when CRISPR is performed in cells or tissues in a dish, but whole genome sequencing has not been employed to look for all off-target effects in living animals," says co-author Alexander Bassuk, MD, PhD, professor of pediatrics at the University of Iowa.

In the new study, the researchers sequenced the entire genome of mice that had undergone CRISPR gene editing in the team's previous study and looked for all mutations, including those that only altered a single nucleotide.

The researchers determined that CRISPR had successfully corrected a gene that causes blindness, but Kellie Schaefer, a PhD student in the lab of Vinit Mahajan, MD, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University, and co-author of the study, found that the genomes of two independent gene therapy recipients had sustained more than 1,500 single-nucleotide mutations and more than 100 larger deletions and insertions. None of these DNA mutations were predicted by computer algorithms that are widely used by researchers to look for off-target effects.

"Researchers who aren't using whole genome sequencing to find off-target effects may be missing potentially important mutations," Dr. Tsang says. "Even a single nucleotide change can have a huge impact."

Dr. Bassuk says the researchers didn't notice anything obviously wrong with their animals. "We're still upbeat about CRISPR," says Dr. Mahajan. "We're physicians, and we know that every new therapy has some potential side effects—but we need to be aware of what they are."

Researchers are currently working to improve the components of the CRISPR system—its gene-cutting enzyme and the RNA that guides the enzyme to the right gene—to increase the efficiency of editing.

"We hope our findings will encourage others to use whole-genome sequencing as a method to determine all the off-target effects of their CRISPR techniques and study different versions for the safest, most accurate editing," Dr. Tsang says.

The paper is titled, "Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo." Additional authors are Kellie A. Schafer (Stanford University), Wen-Hsuan Wu (Columbia University Medical Center), and Diana G. Colgan (Iowa).

But again, even no human on Earth is the same as the idealised combination of his parents genes would be. There are changes in every generation, and really even during life. Identical twins are not identical, and they are becoming less "identical" as they live, accumulating changes, part of which are random.