Leave it to a researcher who studies icy moons in the outer solar system to come up with an out-there scheme to restore vanishing sea ice in the Arctic.Professor Desch and his colleagues estimate that each ice-making buoy would cost $50,000 (including shipping and handling). They estimate that it would cost $500 billion to cover 10% of the Arctic Ocean with ice-making buoys...

Ice is a good insulator, says Steven Desch, a planetary scientist at Arizona State University in Tempe. That's why moons such as Jupiter's Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, among others, may be able to maintain liquid oceans beneath their thick icy surfaces. On Earth, sea ice is much thinner, but the physics is the same. Ice grows on the bottom surface of floating floes. As the water freezes, it releases heat that must make its way up through the ice before escaping into the air. The thicker the ice, the more heat gets trapped, which slows down ice formation. That's bad news for the Arctic, where ice helps keep the planet cool but global warming is causing ice to melt faster than it can be replaced.

The answer to making thicker ice more quickly? Suck up near-freezing water from under the ice and pump it directly onto the ice's surface during the long polar winter. There, the water would freeze more quickly than underneath the ice, where it usually forms.In theory, Desch says, the pumps used for this top-down approach to ice growth could be driven by technology no more sophisticated than the windmills that have long provided water to farms and ranches on the Great Plains.

Desch and colleagues envision putting such pumps on millions of buoys throughout the Arctic. During winter, each pump would be capable of building an additional layer of sea ice up to 1 meter thick over an area of about 100,000 square meters...

[...]

Now is the time to begin detailed designs and build prototypes, Desch says. The Arctic Ocean's end-of-summer sea ice coverage has decreased, on average, more than 13 percent per decade since 1979. "There'll be a time, 10 to 15 years from now, when Arctic sea ice will be accelerating to oblivion, and there'll be political will to do something about climate change," Desch says. "We need to have this figured out by the time people are ready to do something."

Science News

Ice grows on the bottom surface of floating floes. As the water freezes, it releases heat that must make its way up through the ice before escaping into the air. The thicker the ice, the more heat gets trapped, which slows down ice formation. That's bad news for the Arctic, where ice helps keep the planet cool but global warming is causing ice to melt faster than it can be replaced.

So... Thicker ice traps more heat (insulation), causing the ice to melt faster, preventing the ice from keeping the planet cool (high albedo). Makes perfect sense.

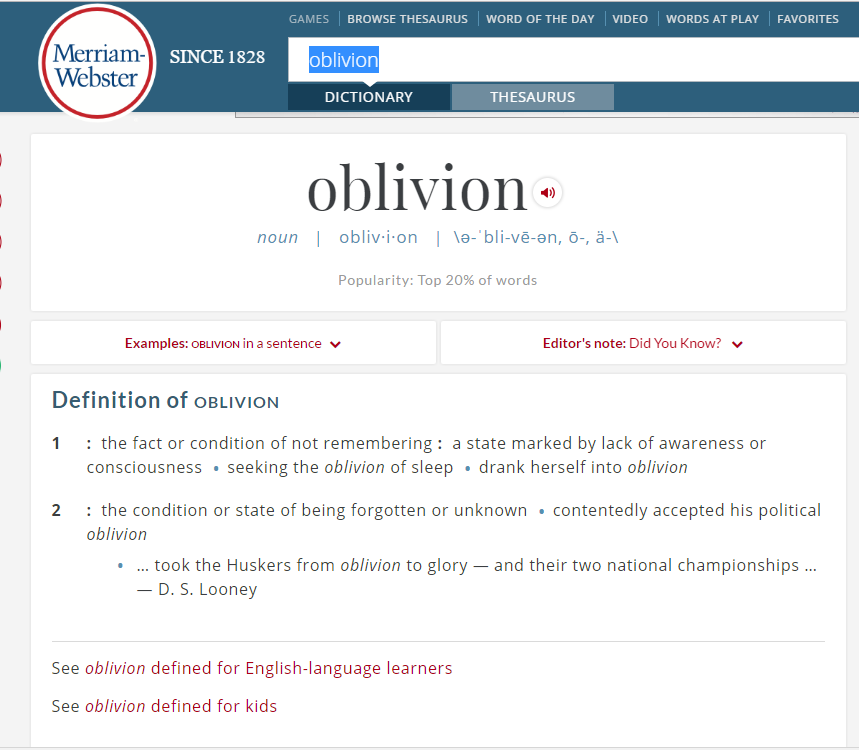

"There'll be a time, 10 to 15 years from now, when Arctic sea ice will be accelerating to oblivion, and there'll be political will to do something about climate change. We need to have this figured out by the time people are ready to do something.""Accelerating to oblivion"? Oblivion?

Since we know that the current Arctic sea ice extent is much larger than that of most of the Holocene, "oblivion" is probably not the place to which Arctic sea ice is heading. If anything, it is returning to normal. So, I don't think these ice-making buoys would be the best place to "invest" $500 billion.

The Arctic was probably ice-free during summer for most of the Holocene up until about 1,000 years ago. McKay et al., 2008 demonstrated that the modern Arctic sea ice cover is anomalously high and the Arctic summer sea surface temperature is anomalously low relative to the rest of the Holocene.

Stranne et al., 2013 demonstrated that the modern day Arctic sea ice extent is more comparable to that of the last Pleistocene glacial stage than to that of the Holocene Climatic Optimum (9,000-5,000 years before present).

References

Alley, R.B. 2000. The Younger Dryas cold interval as viewed from central Greenland. Quaternary Science Reviews 19:213-226.

Desch, S. et al. Arctic ice management. Earth's Future. Vol. 5, January 24, 2017, p. 107. doi: 10.1002/2016EF000410.

McKay, J.L., A. de Vernal, C. Hillaire-Marcel, C. Not, L. Polyak, and D. Darby. 2008.Holocene fluctuations in Arctic sea-ice cover: dinocyst-based reconstructions for the eastern Chukchi Sea. Can. J. Earth Sci. 45: 1377 - 1397

Stranne C, Jakobsson M, Björk G, 2014 Arctic Ocean perennial sea ice breakdown during the Early Holocene Insolation Maximum. Quaternary Science Reviews 92: 123 - 132.

Featured Image

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter