When freelance CIA investigator Dr Andrija Puharich met Uri Geller in 1971, the young Israeli psychic had one driving ambition. And it had nothing to do with spies or science. 'I want to be famous,' insisted Uri, who had grown up in poverty in the backstreets of Tel Aviv.

'I want to be successful. If you want to work with me, you will have to deal with my need for fame and fortune.'

Contacts in the Israeli military told Puharich that this 'unabashed egomaniac' was not worth his trouble.

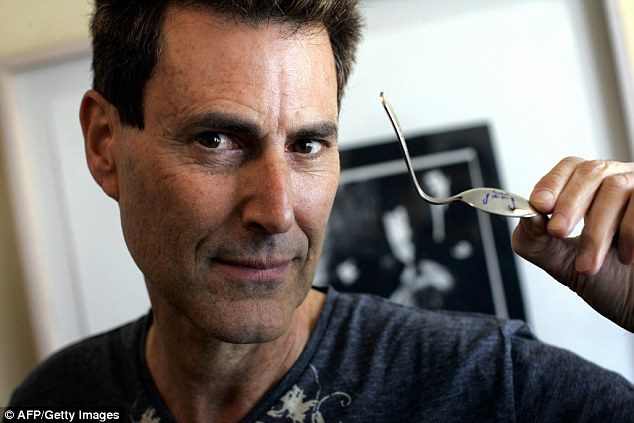

Uri had been a celebrity in his home country, after prime minister Golda Meir joked on the radio about his talent for predicting the future. But his fame was already on the wane and he was reduced to bending spoons and reading minds on stage in tawdry nightclubs. 'You know, we have a word for a kid like Uri — putz, a punk,' one friend told Puharich. 'He really is insufferable.' But early tests left Puharich convinced there was far more to the young man than his outrageous ego.

At the sixth-floor apartment that the eccentric Serbian-American scientist had rented, close to the Mediterranean coast north of Tel Aviv, he conducted basic paranormal exercises. The results stunned him. Uri could accurately pick up three-digit numbers from Puharich's mind when the men were in different rooms. And he could deflect a compass needle by thought. For some reason, they discovered, this effect was strongest when Uri wrapped a rubber band tightly around his wrist as a tourniquet.

One result that fascinated Puharich was Uri's ability to bend a thin stream of water from a tap, by holding his hand a few centimetres away. This is easily done with an electrically charged piece of plastic, such as a comb, but with just a finger it was unprecedented. They noted this effect failed when his finger was wet.

Another test Puharich devised was to see if Uri could direct a beam of energy narrowly or if he produced a random, scattergun effect. He laid out five matchsticks in a row on a glass plate monitored by a film camera. Using psychokinesis —purely mindpower, without physical contact — Uri was able to move whichever matchstick he chose by up to an inch and a quarter. But after a few weeks of this, Uri was getting bored.

One night after dinner at a restaurant, and despite Puharich's protests, he gave a reckless display of driving blindfolded — three miles on hilly roads, at speeds of 50 mph. At one point, behind the wheel and apparently unable to see anything, Uri announced that a red Peugeot was approaching on the other side of the road. Moments later, from around a sharp bend, a red Peugeot appeared.

Perplexed and shaken, Puharich tried to persuade Uri to demonstrate his powers in less flamboyant, self-destructive ways. He urged the arrogant young psychic to go under hypnotism and try talking about his gifts and how they worked.

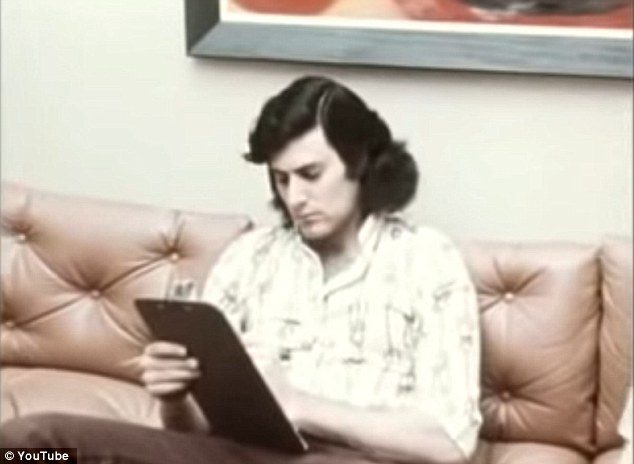

It was Uri's turn to be sceptical. He was immune to hypnotism, he said. But on November 30, 1971, after a late-night cabaret performance at a tatty club called Zorba's, he agreed to lie down on Puharich's living-room sofa and close his eyes, while the scientist counted backwards from 25. By the time the count reached 18, Uri was in a deep trance. He began to talk of fragmented childhood memories. And what he described was stranger than any Hollywood movie.

Uri Geller was born in a Tel Aviv hospital on December 20, 1946. His mother Margaret had already been pregnant eight times and on each occasion had an abortion.

Her husband Tibor, a soldier, was adamant that he did not want children. He was from Hungarian Jewish and gypsy stock, Margaret from the well-to-do Freud family of Vienna: the psychiatrist Sigmund Freud was a distant cousin.

Defying her husband, Margaret kept their ninth child, though her decision nearly broke up the marriage. Tibor was a philanderer and often left his wife and son for long periods to fend for themselves. Devastatingly handsome and impeccably uniformed, Tibor paraded with a series of girlfriends while his wife worked long hours as a seamstress to pay the bills.

As a baby, Uri was almost killed by stray bullets during the street fighting in Tel Aviv that preceded Israeli independence in 1948. Though he was only a few months old, in his pram next to the living room window of his parents' flat, Uri recalled it vividly: 'I remember the glass falling almost in slow motion. 'My mother had put a little teddy bear next to me in the pram, and somehow it rolled over my face and saved me.'

As a toddler, he spent most of each day outside on the street without any supervision.

When he was barely three, on Christmas Day 1949, he had an extraordinary encounter that he would remember vividly for the rest of his life. Opposite the Geller flat there was an old Arabic house on the corner of Yehuda Halevi Boulevard. It was surrounded by a rusty iron fence and, attracted by the sound of kittens mewing, the young Uri slipped inside. The tall grass towered over him. Telling the story to friends over the years, his account never varied:

'I felt something above me and looked up. I saw a ball of light.

'It wasn't the sun — it was something more massive, something that you could touch.

'It was really weird, like a sphere, just hanging there, shining and strobing, and then it gently and silently drifted down towards the ground.

'Then something struck me. It was like a beam or ray of light. It really hit my forehead and knocked me back into the grass.'

Picking himself up, he ran home and tried to tell his mother what had happened. She refused to believe him. But when he recounted the adventure under hypnosis on Andrija Puharich's couch in 1971, an incredible new detail emerged. This time, he described the light as a large, shining bowl from which a figure appeared — faceless, but exuding what Uri said was a 'general radiance'. The figure raised its arms above its head so it appeared to be holding the sun and then became so bright that Uri passed out.

When he came out of his hypnotic trance, Uri listened to the recording of his session with Puharich. He claimed not to remember anything he had said — and when his voice on the tape began to describe the events in the Arabic garden, he became frightened and agitated. Ejecting the cassette, he rushed out of the apartment. It was half an hour before Puharich found him, dazed and motionless 'like a standing mummy'.

Days after Uri Geller described his childhood encounter with the mysterious ball of light, he and investigator Andrija Puharich had another inexplicable experience. It began with a test: the scientist handed the psychic a heavy wooden box with a fountain pen locked inside and asked whether he could make the pen disappear without opening the box. Uri concentrated for several minutes but, when the lid was opened, the pen was still inside the box. But on closer inspection, the brass ink cartridge inside the barrel had vanished.

A few days later, they were driving at night in a Tel Aviv suburb when they saw a bluish, pulsing ball of light above a building site. Uri demanded they pull over and leapt out of the car to take a closer look, telling the scientist to stay where he was. Moments later, he disappeared from view. When he returned, Uri claimed he had been plunged into a trance state once more and had stepped inside the ball of light. A dark shape had loomed close to him and pressed something into his hand. When he uncurled his fingers, he was holding the brass cartridge from the fountain pen.

To Uri Geller, the moment he was struck by the beam of light was the moment his powers were activated. Whether the phenomenon was purely physical (ball lightning, for example) or something paranormal and even extraterrestrial, it changed his life forever. But bizarre and unique as it was, the story was unverified. Even the account he gave under hypnosis proved nothing. That was to change more than 35 years later when a credible witness came forward, out of the blue, to say he had witnessed what happened.

In 2007, having seen a TV documentary about the star that talked about his strange childhood experience, retired Israeli reserve air force captain Ya'akov Avrahami contacted Uri to tell him he had been walking to the bus stop on Yehuda Halevi Boulevard on Christmas Day 1949.

'Suddenly, I saw a powerful light, a sphere-shaped light, a metre in diameter, bright and dazzling,' he said.

'At the same moment, I noticed from the building on the left a small child coming out, dressed in a white shirt and black trousers.

'The light halted again and, as if it had senses, it suddenly turned around and approached the child. The light embraced him.'

Then, he said, the boy ran to an apartment building, with the light following him.

When he went through the door, the light apparently exploded on the side of the building, leaving a black residue.

'After being told all these years that it was my imagination or that I was hallucinating, for this man to come forward was a very emotional thing for me,' says Uri. 'The way he described me as a little boy, with the white shirt and black trousers, which is how my mother always dressed me — that convinced me he was not lying.'

A few days after the strange encounter with sphere of light in the Arabic garden, Uri and his mother were eating soup at their kitchen table when the stem of his spoon suddenly drooped and deposited a splash of hot liquid in his lap. Margaret inspected the spoon. 'It must be loose,' she decided. Even at the age of three, Uri thought that was odd — spoons don't get 'loose'.

After he started school, his father gave him a watch. Bored in class, he would stare at the hands. One day, he saw them leap forward, whirling round on their own. He shouted out 'Look at this watch!' and learned his first hard lesson about skeptics — his classmates refused to believe him and laughed at his claim. Angry and embarrassed, young Uri decided he must have a 'weird watch' and refused to wear it.

Saving her pennies from her work as a needlewoman, his mother bought him another watch, a better one. This time when he stared at it, the hands bent upwards and hit the glass cover. His father was angry, but Margaret was not: she had seen metal bend in the presence of her son and decided to regard it as a special talent, not a curse.

The marriage was disintegrating, and aged ten, Uri was sent to live on a kibbutz near Ashdod, which specialised in children from broken homes. Friends from those days remember his eerie ability to foretell the future. One day he announced in class that 'something terrible' was going to happen in the wheat fields. The next day, a military jet missed the runway of the neighbouring airbase and crash-landed in the corn.

When Margaret remarried, to a former concert pianist called Ladislas, she reclaimed her son from the kibbutz and they moved to Cyprus to run a motel in Nicosia.

At this Christian establishment, he was known as George Geller. Teachers started to notice his abilities. He never seemed to work hard, but he got consistently high marks in exams, even in subjects that he didn't appear to understand. Oddly, his exam papers often mirrored those of the top students — even mimicking their mistakes. Accused of copying, Uri denied cheating, but admitted that he could look at the back of a classmate's head and see what they were writing. He didn't mean to do it, he said — the words appeared, as if on a TV screen in his mind.

He also revealed a talent on the basketball court. When he threw the ball, it would swerve in mid air and the hoop seemed almost to lean towards it. Teacher Joy Philipou said: 'He could shoot from almost anywhere. He never missed the basket. 'I thought it must be my imagination, but several people began to talk about it. In truth, it was scary.'

By the time he was 18, Uri was eager for army service and was desperate to make his soldier father proud. Volunteering for the paratroops, he began basic training and dreamed that one day, if he became an officer, he could join the secret services and use his telepathic gifts as a spy.

The Six Day War put an end to his fantasies. In June 1967, 18 months after he joined up, his unit was ordered into action to cut off enemy supply lines to Jerusalem. Caught in an ambush by Jordanian tanks, he and his comrades took shelter in a graveyard, and Uri was hit in the left elbow by a bullet.

He staunched the blood with bandages. Minutes later, he saw his best friend Avram killed by a tank shell. Pinned down by fire from a pillbox above them, Uri led a party to knock it out. As they worked their way up, a Jordanian soldier leapt out from behind a rock and fired twice, missing from just a few yards away. With his gun at waist level, Uri returned fire. He said he was looking the soldier in the face as he killed him. A few moments later, he was hit himself — either by a ricochet or by a stray bullet. Wounded in the head and right arm, he passed out.

Weeks later, he was discharged from hospital — badly scarred on both arms and unable to fully straighten his left elbow, but alive. With his hopes of a military career wrecked, but still a serving soldier, he was given an assignment where he could recuperate, and sent to organise a government summer camp for children.

Tasked with entertaining them, Uri showed the youngsters his abilities to read minds and bend metal. Word got around and before long he was invited on national TV. At that point, the security services started taking an interest. Prime minister Golda Meir invited him to a party and quizzed him on his vision of Israel's future.

Defence minister Moshe Dayan, a war hero famous for his black eyepatch, took a less esoteric interest — he wanted to know if Uri could locate buried archaeological treasures.

The turning point came in September 1970, when Uri was performing at the Tzavta theatre in Tel Aviv. He suddenly stopped in mid-act, looked ill, sat down and asked if there was a doctor in the house. Then he started to ramble — he said an enormous event with a massive significance for Israel was about to occur.

Suddenly, he became specific. President Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt's hardline dictator, was dead, he announced. He was certain of it. The show was halted and the audience filed out. One journalist in the auditorium rushed to a phone, called the newsdesk to check and reported back that there were no rumours that Nasser was dead or even ill.

It was not until the next day that the news became public: the Egyptian leader had died of a heart attack, the night that Uri broke the news from the stage. That striking incident made him a national celebrity. Prime minister Meir joked on the radio: 'They say there's a young man who can foresee exactly what will happen. I can't!'

And across the Atlantic, the CIA began to take an interest. Fame and fortune...Uri Geller was about to get his heart's desire.

Adapted from The Secret Life Of Uri Geller by Jonathan Margolis.

Comment: Further reading: