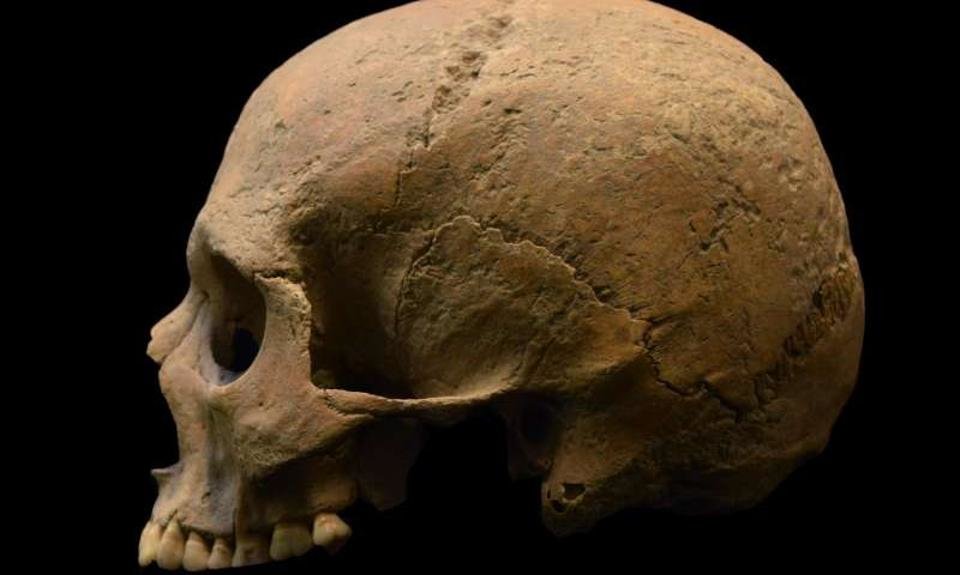

© Luca Bondioli / Pigorini MuseumSkeletal remains of an individual from Velia, Italy are shown.

In today's issue of

Current Biology, an international group of researchers has published some of the first direct DNA evidence of malaria in Imperial Italy. While the study did not find DNA of

Plasmodium falciparum in skeletal remains near Rome, the discovery points to a way forward in our understanding of disease and death in the Roman Empire.

The team, led by Stephanie Marciniak of McMaster University, investigated 58 skeletons in total from Isola Sacra (the cemetery associated with Portus Romae, about 25 km from Rome on the coast), Velia (a site in southwestern Italy), and Vagnari (in southeastern Italy). All date to the 1st-4th centuries, or the Imperial period. They found evidence of

P. falciparum, the organism that causes malaria, in two individuals -- one from Velia and one from Vagnari.

There are two interesting outcomes from this project -- first, that the researchers have found evidence of malaria that tracks the assumed geographical spread. That is, given the evidence of malaria further south in earlier time periods, Marciniak and colleagues show a northward spread of the disease through DNA evidence. And second, that the researchers found no evidence of malaria in the sample from Portus Romae.

Portus was Rome's port city, and neighboring Ostia Antica was famously abandoned because of malaria in the 9th century AD. Of course, DNA testing is expensive, and not every person had malaria, so it is entirely possible that the researchers simply missed the skeletons that had malaria.

I have no doubt that DNA evidence of malaria will be found in Imperial Rome in short order. But as an expert in the bioarchaeology of ancient Rome, I do caution against extrapolation of these data to Rome -- and especially caution against the extrapolation of malaria DNA data to a "fall of the Roman Empire" scenario.

DNA evidence from Roman Italy is still in its infancy as a field, even more so than bioarchaeology in Roman Italy, which itself is a small field and still fraught with issues of replicability. As I note in my forthcoming article on "Imperialism and Physiological Stress in Rome," there is a diversity in health outcomes as seen in skeletal data, which means that the common perception of life in urban Rome as one full of violence, stress and disease is simply not the only story. Further, I write that "understanding the variation in health and the disease load of the population of this massive pre-industrial urban center is complicated by geography, disease ecology, diet and genetic variation, as well as by inconsistent reporting of osteological data in the bioarchaeological literature."

That is, we need a whole bunch more information from skeletons and DNA before drawing historical conclusions about the health of Romans during the Empire. In particular, it will be great to see Rome and Imperial Italy mapped using GIS and skeletal data to better understand how human-environment interaction played out in susceptibility to disease.

This is all to say that the Marciniak et al. article on DNA from Imperial Italy is a testament to how far we have come in understanding ancient disease. Their work is solid, and their interpretations are cautious, as they should be. Unfortunately, we are already seeing media outlets crowing about malaria causing widespread death in ancient Rome (

Daily Mail, of course).

The story is

much more complicated than a single-reason cause for collapse -- and

much more interesting. We have years of work ahead of us to understand this complexity, and it is exciting to stand at that threshold where we will soon know more about the life and death of Imperial Rome.

References:Marciniak, S. et al. 2016.

Plasmodium falciparum malaria in 1st-2nd century CE in southern Italy.

Current Biology 26(R1-3).

Killgrove, K. 2017. Imperialism and physiological stress in Rome (1st-3rd centuries AD). In

Colonized Bodies, Worlds Transformed: Toward a Global Bioarchaeology of Contact and Colonialism, H. Klaus and M. Murphy, eds., Ch. 9., pp. 247-277. University Press of Florida.

Kristina Killgrove writes about archaeology, anthropology, and the classical world.

you wanted to disable an entire opposition group to ensure your dominance, perhaps you would use an ancient bacteria or virus that had been around long enough to have created its own immunity in the masses of population.

Like leprosy.

Then the slow introduction of this ancient disease would fail to be recognized and diagnosed as a multitude of other non-fatal like diabetes, sarcoidosis, etc.

Leprosy is ideal from the standpoint of a disease that slowly saps the body creating weakness. A low-energy population isn't going to upset the current apple cart. Its extremely slow progression would guarantee its continuance.

The future of population control is such. The future of warfare is such. The future of economic dominance is such.

My guess is that the number one global target for economic dominance is control and sequestration of the biologic herbals.