The director of the National Security Agency forcefully and emotionally rejected calls to curtail his agency's power on Tuesday, as legislation to reform the US security services was introduced in Congress against the backdrop of a growing diplomatic crisis.

General Keith Alexander, the director of the NSA, speaking "from the heart" before a Tuesday hearing of the House intelligence committee, said the NSA would prefer to "take the beatings" from the public and in the media "than to give up a program that would result in this nation being attacked."

Alexander spoke hours after bills came before the House and Senate judiciary committees that would end the NSA's bulk collection of Americans' phone records, sponsored by Congressman James Sensenbrenner, a Wisconsin Republican, and Senator Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat.

The program, performed under authorities claimed under the Patriot Act - which Sensenbrenner helped draft in 2001 - was first revealed in June by the Guardian from material leaked by whistleblower Edward Snowden.

Alexander said that in the past year the NSA collected "billions" of records from Americans under the program, but, as in past testimony, said it was only searched by a handful of NSA officials possessing "reasonable articulable suspicion" of connection to a specified terrorist group, and searched fewer than 300 times over the past year.

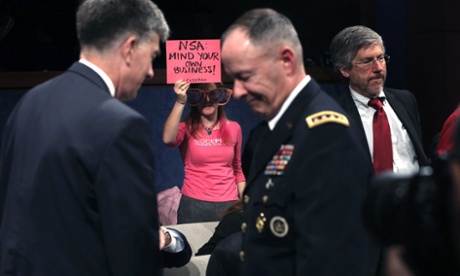

Alexander, accompanied by the embattled director of national intelligence James Clapper and other NSA and Justice Department officials, argued that a continued threat of terrorism justified retaining the NSA's post-9/11 powers. He and his colleagues have contended that since 9/11, they have prevented 54 terrorist plots, although under congressional pressure, they have not argued that the domestic phone records collection has been a leading factor in the thwarted plots.

Addressing an international row over NSA spying on the US European allies over the past week, Alexander forcefully argued that reports of the agency collecting millions of phone calls were "absolutely false". He said: "Those screenshots that show or at least lead people to believe that we, NSA, or the US, collected that information is false - and it is false that it was collected on European citizens. It was neither."

Alexander and Clapper focused mainly on a defense of their existing powers, although the hearing was called to solicit their perspectives on surveillance reforms.

Clapper, who is under political fire after apologizing to the Senate for misleading it on domestic surveillance, invoked the specter of Vietnam-era abuses - a sign of how seriously the intelligence community sees its current political predicament - to say "the intelligence community today is not like that."

Clapper explicitly warned the panel to be mindful of the "risks of overcorrection" in surveillance reform - suggesting, as Alexander did, that proposed restrictions on bulk surveillance would leave the country in danger of a terrorist attack.

That perspective has strong advocates on the House committee, which has proposed alternatives to the Leahy and Sensenbrenner bills. Chairman Mike Rogers, a Michigan Republican, proposed increasing the public's visibility into the NSA's activities without substantially curtailing them.

Rogers's Democratic counterpart, Charles "Dutch" Ruppersberger of Maryland, said he favored a "meaningful process of reform that will enhance transparency and privacy, while maintaining the necessary capabilities to protect this nation." He added: "We don't want to make it easier to be a terrorist than a criminal in this country."

A complementary bill, supported by California Democrat Dianne Feinstein, was marked up in the Senate intelligence committee, the first stage in a bill becoming law. A day earlier, Feinstein, a staunch NSA ally, rebuked the agency over spying on foreign leaders.

But there is an increasing sense in Washington that Congress, and perhaps the White House, will impose some form of limitation on the NSA's authorities - a rarity since 9/11. Even Ruppersberger, another staunch NSA ally, signaled he was open to transforming the collection of Americans' call data.

"Can we move away from bulk collection and toward a system like the one used in the criminal prosecution system, in which the government subpoenas individual call data records - phone numbers, no content - to be used for link analysis?" Ruppersberger asked.

John Inglis, Alexander's deputy at NSA, did not commit to moving away from domestic bulk collection, but said "numerous technical architectures" are "viable," provided they have privacy procedures; the records are comprehensive; they can be stored for three to five years; and can provide "agility" to time-pressured intelligence analysts.

The testimony of Alexander and Clapper came against another backdrop: an increasing acrimony, playing out through anonymous sources in the press, between the White House and the NSA.

Ever since German chancellor Angela Merkel confronted President Obama over allegations that NSA spied on her phone, a struggle has broken out between Fort Meade and the White House over responsibility for a growing diplomatic controversy - particularly over how aware Obama was of the spying on his foreign counterparts.

That struggle came on the eve of the surveillance reform debate in Congress, raising questions about how strongly the White House will fight the reform efforts.

Dancing around the central question of how much Obama knew about NSA spying on foreign leaders, Clapper testified that the intelligence agencies "do only what the policymakers, writ large, have actually asked us to do." But he added that the "level of detail" about how those requirements are implemented rarely rises to the attention of presidents.

Two Democratic representatives, Representative Adam Schiff of California and Jan Schakowski of Illinois, suggested that the House intelligence committee was not informed about the eavesdropping on foreign leaders. Clapper, without confirming that the spying took place, said that "we have by and large complied with the spirit and intent of the law".

Schiff drew a heated and unexpected rebuke from Rogers, who called his suggestion "disingenuous." The committee has access to "mounds of product" from the NSA, Rogers said.

Schiff shot back a direct question about whether Rogers in fact knew about the foreign leader spying, which Rogers said he could not answer without confirming - but invited the committee member to view reams of intelligence in private.

Stewart Baker, a former NSA attorney, said the divide appeared to be driven by "mainly ex-officials," and reflected a surprise that the Obama administration would back away from spying on foreign leaders, a traditional NSA activity.

"I think it's mainly people who know the agency but are no longer constrained by obligations to the president. Mainly ex-officials," Baker told the Guardian. "I think they are genuinely shocked at the idea that intelligence agencies are supposed to respect the privacy of some global community. That's very post-national; and intelligence agencies are the last places you'd expect to find post-nationalists. Even after 50 years of the European Union, they're all still spying on each other."

Baker, who also testified at the House hearing, said the NSA had "neither the tools nor the disposition to defy the White House," and there was little peril of a narrative of dispute "unless the Guardian tries to keep one alive."

"The risk for the White House is the Republicans in Congress will decide that the president is selling the intelligence community out," Baker said.

So.... we're all wondering which one of these 'dudes' they're going to "sacrifice" in order to protect the evil that currently destroying their country?