When we hear about the psychology of crowds, it's often in an unsavory context. "Group-Think Makes Killers," reads the title of this article by social psychologist Bernd Simon, who cites the infamous Stanford Prison Experiment as an example of how giving up "I" for "We" can have nasty consequences.

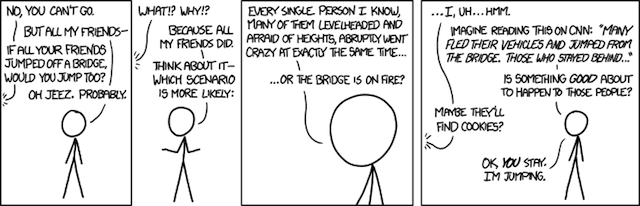

Crowd psychology is often singled out as the catalyst that drives the transformation of a civil protest into an unruly riot. "When you are in a crowd, you are more likely to behave as others do, even if it is against your own personal belief system," explains psychologist Stephanie Sarkis in Psychology Today.

"And others' behavior can be contagious - people get "wrapped up" in the behavior. Those with ulterior motives (looting, for example) take an opportunity in the midst of chaos to commit an anonymous act." Still, exceptions, caveats, and counterarguments to nefarious instances of group-think abound.

Ideas on crowd psychology, and how to confront it, have evolved in recent years. "The classical view of all crowd members... being inherently irrational and suggestible, and therefore potentially violent, is both wrong and potentially dangerous," writes psychologist Stephen Reicher in a paper exploring how police can go about maintaining public order more safely and effectively.

In 2005, sociologists David Schweingruber and Ronald Wohlstein concluded that the broadly held conception of crowds as volatile and dangerous entities is largely unfounded. The researchers go on to list seven "myths" about crowds (widely promoted, they found, by intro sociology textbooks) that lack empirical support "and have been rejected by scholars in the field." PsyBlog's Jeremy Dean gives a great overview of all seven of Schweingruber and Wohlstein's identified myths. For the sake of brevity, here's his tidy counterargument to the notion that crowds are irrational:

Crowds, moreover, can also be wise. There's also lots to be said for collective intelligence.One type of irrationality frequently attributed to crowds is panic. Faced by emergency situations people are thought to suddenly behave like selfish animals, trampling others in the scramble to escape.

A long line of research into the way people behave in real emergency situations does not support this idea. Two examples are studies on underground station evacuations and the rapid, orderly way in which people evacuated the World Trade Center after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Many lives were saved that day because people resisted the urge to panic. Resisting the urge to irrationality, or panic, is the norm.

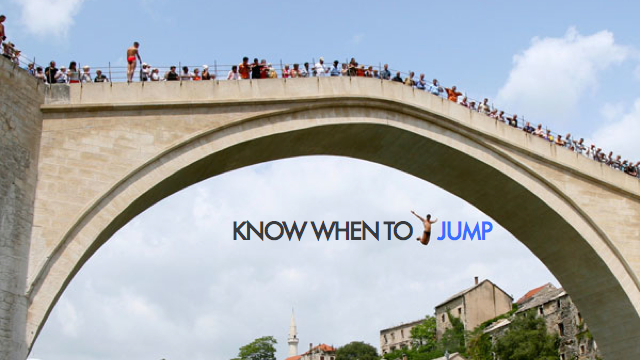

And while concepts like wisdom of the crowd and co-intelligence may not always be directly applicable to the spontaneously arising situations often associated with group-think, sometimes a burning bridge is a burning bridge... in which case you should probably join your friends and take the leap. Just remember: aim for a feet-first, knife-like entry. And don't forget to clench your butt.

Black Friday