Since the previous rounds of QE didn't succeed in reviving the economy (although they may have staved off more decline) it isn't clear why a third round should do the trick.

Although stock markets predictably rallied at the prospect of more cheap money and continued low interest rates (which means investors might hope to do better in stocks than in bonds) Bernanke's real motive may have been as much political as economic.

He is buying time and keeping the show on the road until such time as the politicians get their act together and reach a rational compromise on spending cuts and tax rises.

The U.S. Congress being the dysfunctional beast it has now become, Bernanke is probably not holding his breath until such a happy outcome emerges. So if Congress decides to jump off the fiscal cliff at the end of this year, Bernanke may also be hinting that the Fed will do what it can to stave off disaster.

The second striking development was the news from Europe that the head of the Bundesbank, Jens Weidmann, threatened to resign over the plans of the European Central Bank to buy more bonds of near-bankrupt eurozone members like Spain and Italy.

"One should not underestimate the danger that financing by central banks can get one hooked like a drug," Weidmann warned in Der Spiegel magazine and opinion polls suggest that his doubts over the ECB strategy are supported by a majority of Germans.

To lose one Bundesbank chief, as Germany did when Weidmann's predecessor Axel Weber resigned in 2011, may be seen as a misfortune. To lose two over the same unpleasant issue of hard-working Germans bailing out improvident southern Europeans, is a serious political crisis in Germany and an economic one for Europe.

The crisis in the German political-financial establishment is all the deeper in that another German, the ECB's former chief economist Jurgen Stark, also chose to depart.

The German economy looks like following the rest of Europe into a double-dip recession, after a key purchasing managers' index indicated new export orders dropping at their fastest rate in three years and the manufacturing sector shrinking for the sixth month on a row.

The third sobering development came from China, where an official survey found that manufacturing activity unexpectedly shrank in August and the country's top five banks reported a 27 percent jump in non-performing loans in the first half of this year. An unofficial survey from the HSBC bank was even gloomier, reporting Monday that Chinese manufacturing output was contracting as it had in March, 2009, the deepest point of the crisis.

The Shanghai Composite stock market index fell again last week and is down 13 percent this quarter, again near the depths it plumbed in early 2009, at the peak of the financial crisis.

It now looks highly probable that the 7.5 percent annual growth target for this year, set by Premier Wen Jiabao, will be missed, and many observers think it could fall to less than 7 percent. Stocks of unsold goods, from cars to washing machines, are piling up in warehouses, along with mounting stocks of raw material from coal (which signals low demand for electricity) to rubber and copper.

One curious aspect of the China slowdown appeared to emerge from Iran, which has suspended a $3 billion contract for a Chinese company to build a liquefied natural gas plant in the Persian Gulf port of Asaluyeh "until further notice." Iran's state-run Mehr news agency said that the Chinese group had been unable to raise the required finance.

There may be other reasons behind this surprise announcement, ranging from a Chinese signal that it is prepared at least to pay lip service to the U.N. sanctions program against Iran's nuclear ambitions, to the prospect of a coming glut in LNG supplies now that the United States is producing so much of its own shale gas.

Norway's Statoil, for example, has forfeited more than $300 million to pull out of its planned development of offshore LNG from Russia's Shtokman field in the arctic, although this may be as much frustration with Russian partners as fear of glut in LNG.

The point is that there is very little heartening news coming for the global economy from any quarter.

In Europe, the United States and China, who between them account for more than 60 percent of the world's output, the prospects are uniformly dismal.

And those who object that at least we have been spared a 1930s-style Great Depression should recall that remark of the English historian A. J. P. Taylor, that "all we learn from the mistakes of the past is how to make new ones."

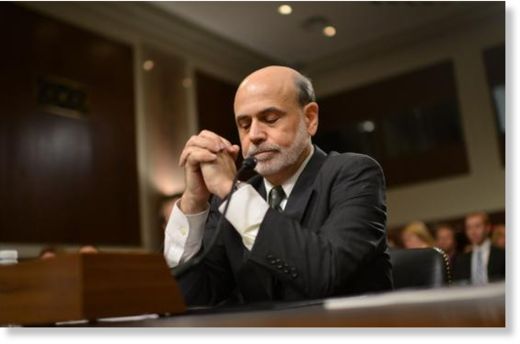

Is Berwanke testifying or praying...? shoulnt he be wearing one of those protective pidgeon shit caps on his barnet too...?