Rules without tyranny is harder than it seems

© anonplus

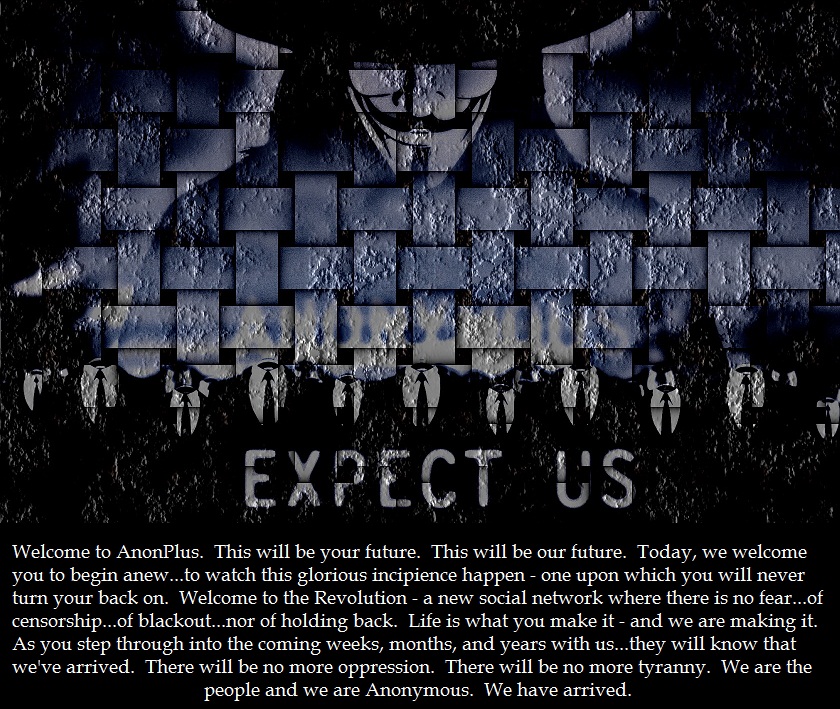

The story so far is that Anonymous - or someone associated with Anonymous, or someone cynically riding on the back of Anonymous, who knows? - has set up a site that's going to offer some kind of social network.

According to TechSpot, the idea (and the "Alpha" Website,

anonplus.com) arose when Google+ allegedly banned an unknown number of Anonymous members.

The Anonplus site is couched in Anonymous' usual grandiose phraseology - "they will know that we have arrived. There will be no oppression. There will be no more tyranny. We are the people and we are Anonymous."

OK, fair enough. Anyone's got the right to set up a social network if they want, and they the right to claim to act on behalf of others, regardless of how accurate that claim may be.

But the idea of a completely anarchic, "no tyranny, no oppression" (defined in whose terms?) social network does offer up some interesting self-contradictions to resolve.

I'll grant that the world of corporate social networks is a nightmare of "tyranny and oppression" - so much so that the success of Facebook and the excitement over Google+ mystifies me. Facebook bans a Google+ ad at the drop of a hat, but turns into a nearly-immovable object if asked to help deal with abusive commenters (who, for example, infest tribute pages to the dead). Google+ demands an understanding of 37 different privacy statements. Social networks are not just tyrannical, they're also a "confusopoly" whose success depends on nobody being able to decode the rules they've promised to follow.

Anonymous' intervention - to me, a much more welcome intervention than the group's inability to distinguish between targets, slapping the small and mighty with equal abandon and claiming equal credit whether they've defeated a flea-bite nobody or a US military operation - may or may not succeed, but it raises an interesting question.

What's the line separating rules that are necessary for a social network to function from rules that are oppressive, and when does one become the other?

All social interactions are government by rules of some kind. They may be tight or loose, consensual or tyrannical, explicit or implicit, designed or evolved, but the rules exist, whether or not you follow them (or even acknowledge them).

If all you do is hold a conversation with someone, you will follow at least one rule - the two of you will hold the conversation in languages comprehensible to you both. The interaction won't happen without that minimum rule.

"If we hack something, we publish it" is a rule for Anonymous - written or not. "There will be no tyranny" is a rule of interaction.

And even Anonplus.com must have, at minimum, one rule: "anybody may join". The group itself has implied a second rule, that nobody be censored or blacked out.

Censorship provides a convenient handle on which I can hang a question about rules: censorship by whom? Sure, it's clear that "Anonplus" won't censor the statements or posts of its users - but what of those users who would wish to constrain, censor or silence other users?

Such people exist in every large group - whether they merely seek to shout down dissent or, since this is the Internet, if they seek to silence those they don't like by hacking their profiles.

"We will not censor" is one rule, one which governs only part of the interaction: "You will not censor" is another - one which, in both its expression and enforcement, contains the potential for tyranny. The more difficult "do not hack other users' profiles" holds even better tyrannical potential, since it involves questions of accusation, evidence, proof, appeal and enforcement.

These are merely a couple of simplistic examples. The greater the subtlety and complexity of the interaction, the more subtle and complex the rules that govern it.

Anonplus already has rules. To grow into something that has users - users outside its own inner circle - it faces a much tougher task. It must learn to walk a tightrope between the tyranny of rules and the tyranny of anarchy. If it succeeds, it will be a welcome coming-of-age.

Who would trust these guys enough to join their social network -- assuming that the vaporous dream ever becomes so much as a smidgeon of reality?