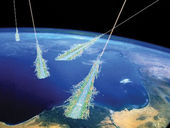

© Simon Swordy/University of Chicago, NASAThe shower of particles produced when Earth's atmosphere is struck by ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (the most energetic particles known in the universe).

There's some interesting information of the six month trend of neutrons being detected globally that I want to bring to discussion, but first I thought that a primer on cosmic rays, neutrons, and their interaction with the atmosphere might be helpful to the many layman readers here. - Anthony

Cosmic rays are energetic particles that originate in space and our sun and collide with particles as they zip through our atmosphere. While they come from all directions in space, and the origination of many of these cosmic rays is unknown, they has recently been shown that a larger percentage emanate from specific

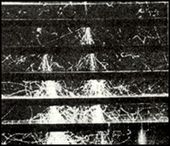

deep space sources. Cosmic rays were originally discovered because of the ionization they produce in our atmosphere. They cause ionization trails in the atmosphere much like you see in a simple science project called a cloud chamber, shown below right:

© unknownUsing the Wilson cloud chamber, in 1927, Dimitr Skobelzyn photographed the first ghostly tracks left by cosmic rays.

In the past, we have often referred to cosmic rays as "galactic cosmic rays" or GCR's, because we did not know where they originated. Now scientists have determined that the sun discharges a significant amount of these high-energy particles. "

Solar Cosmic Rays" (SCR's - cosmic rays from the sun) originate in the sun's

chromosphere. Most solar cosmic ray events correlate relatively well with solar flares. However, they tend to be at much lower energies than their galactic cousins.