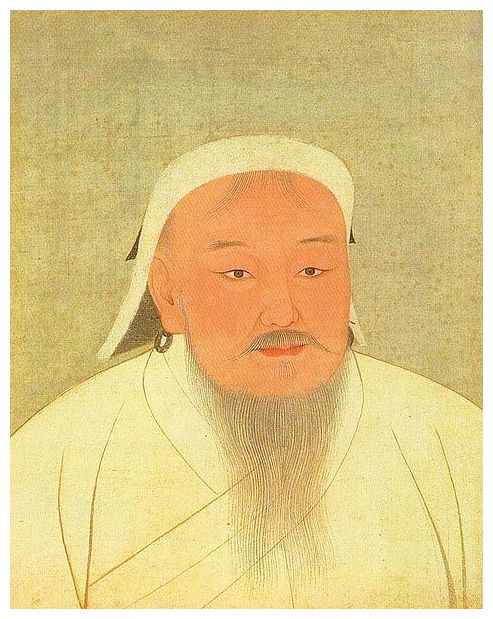

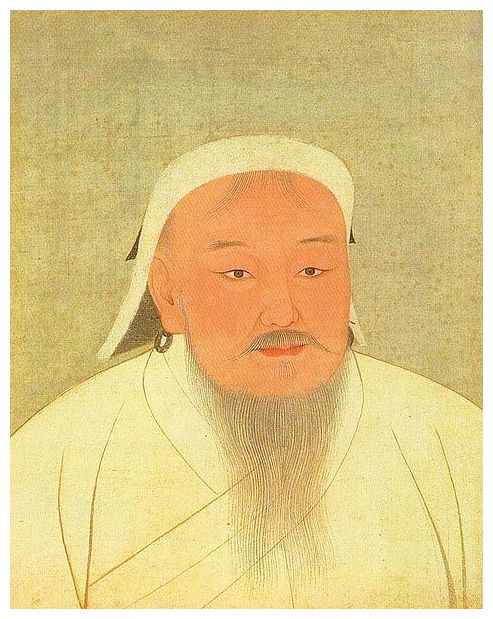

© Wikimedia CommonsGenghis Khan

For centuries historians and treasure seekers have searched for the burial site of history's most famous conqueror. New findings offer compelling evidence that it's been found. Oliver Steed reports

IN the 800 years since his death, people have sought in vain for the grave of Genghis Khan, the 13th-century conqueror and imperial ruler who, at the time of his death, occupied the largest contiguous empire, stretching from the Caspian Sea to the Pacific. In capturing most of central Asia and China, his armies killed and pillaged, but also forged new links between East and West. One of history's most brilliant and ruthless leaders, Khan remade the world.

But while the life of the conqueror is the stuff of legend, his death is shrouded in the mist of myths. Some historians believe he died from wounds sustained in battle; others that he fell off his horse or died from illness. And his final burial place has never been found. At the time great steps were taken to hide the grave to protect it from potential grave robbers. Tomb hunters have little to go on, given the dearth of primary historical sources. Legend has it that Khan's funeral escort killed anyone who crossed their path to conceal where the conqueror was buried. Those who constructed the funeral tomb were also killed - as were the soldiers who killed them. One historical source holds that 10,000 horsemen "trampled the ground so as to make it even"; another that a forest was planted over the site, a river diverted.

Scholars still debate the balance between fact and fiction, as accounts were forged and distorted. But many historians believe that Khan wasn't buried alone: his successors are thought to have been entombed with him in a vast necropolis, possibly containing treasures and loot from his extensive conquests.

Germans, Japanese, Americans, Russians, and the British all have led expeditions in search of his grave, spending millions of dollars. All have failed. The location of the tomb has been one of archeology's most enduring mysteries.

Until now.

A multidisciplinary research project uniting scientists in America with Mongolian scholars and archeologists has the first compelling evidence of the location of Khan's burial site and the necropolis of the Mongol imperial family on a mountain range in a remote area in northwestern Mongolia.

Among the discoveries by the team are the foundations of what appears to be a large structure from the 13th or 14th century, in an area that has historically been associated with this grave. Scientists have also found a wide range of artifacts that include arrowheads, porcelain, and a variety of building material.

"Everything lines up in a very compelling way," says Albert Lin,

National Geographic explorer and principal investigator of the project, in an exclusive interview with

Newsweek.