Book dealer Ken Sanders has seen a lot of nothing in his decades appraising "rare" finds pulled from attics and basements, storage sheds and closets.

Sanders, who occasionally appraises items for PBS's Antiques Roadshow, often employs "the fine art of letting people down gently."

But on a recent Saturday while volunteering at a fundraiser for the small town museum in Sandy, Utah, just south of Salt Lake, Sanders got the surprise of a lifetime.

"Late in the afternoon, a man sat down and started unwrapping a book from a big plastic sack, informing me he had a really, really old book and he thought it might be worth some money," he said. "I kinda start, oh boy, I've heard this before."

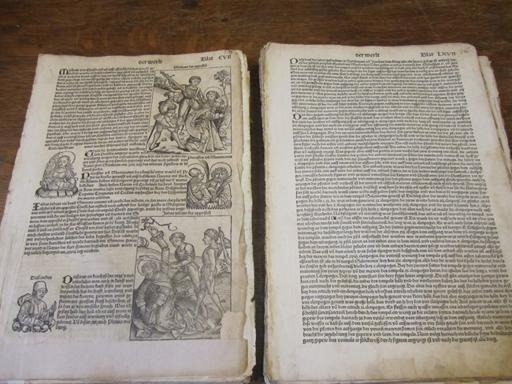

Then he produced a tattered, partial copy of the 500-year-old Nuremberg Chronicle.

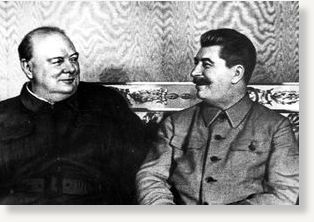

Comment: Could Stalin's "brain illness" be in fact a frontal characteropathy, as described by Andrew M, Lobaczewski in Political Ponerology (A Science on the Nature of Evil Adjusted for Political Purposes)?