The Nigerian-led Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) has rejected a three-year transition plan leading to elections put forward by the coup leaders, putting Ecowas and Niger on a path toward war. Since the junta, led by Gen. Abdourahamane Tiani, seized power following a bloodless coup on Jul. 26, Ecowas has taken a hardline position that Bazoum must be restored to power, or else the organization — originally created in 1975 to promote trade relations but since having moved on to using collective force to maintain regional security — would intervene militarily.

Any Ecowas military intervention would be complicated by the presence of US, French and European military personnel in Niger. As a former French colony, Niger has long hosted a sizeable French military presence. This provides security for uranium fields in Niger owned and operated by France, as well as supporting regional security efforts designed to defeat Islamic terrorists operating in the Sahel. The US likewise supports this counterterrorism effort, and views Niger, where the US maintains two large bases, as the foundation of its military presence in West Africa.

The junta led by Gen. Tiani was partly motivated by a rejection of France's post-colonial presence in Niger and perceptions that France continues to exploit the people of Niger politically and economically. While the US has sent a high-level delegation led by acting Deputy Secretary of State Victoria Nuland to argue for Bazoum's return to power, it has not openly backed military intervention. This puts it at odds with the French, who are supportive of Ecowas' demands that Bazoum be reinstated or else.

What a War Would Look Like

Any military incursion by Ecowas into Niger, whether supported by France or not, would be doomed to fail from the start, argues the Abuja-based Office for Strategic Preparedness and Resilience, a Nigerian government think tank. It has called any such intervention "costly and infeasible," and noted it would lead to "catastrophically counterproductive consequences for West Africa."

Nigeria is the major military power in Ecowas and, as such, would shoulder the burden for any such conflict. But the Nigerian army is already overstretched trying to deal with terrorists from Boko Haram, an Islamic State-affiliated terrorist group operating in both Niger and Nigeria. Moreover, whatever successes Nigeria enjoys against Boko Haram are linked to the operations of the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), which includes Niger. If a Nigerian-led Ecowas military force invaded Niger, Niger would undoubtedly withdraw from the MNJTF. This could trigger a surge in Boko Haram activity that would strip away military forces that could otherwise be used to support the Ecowas effort.

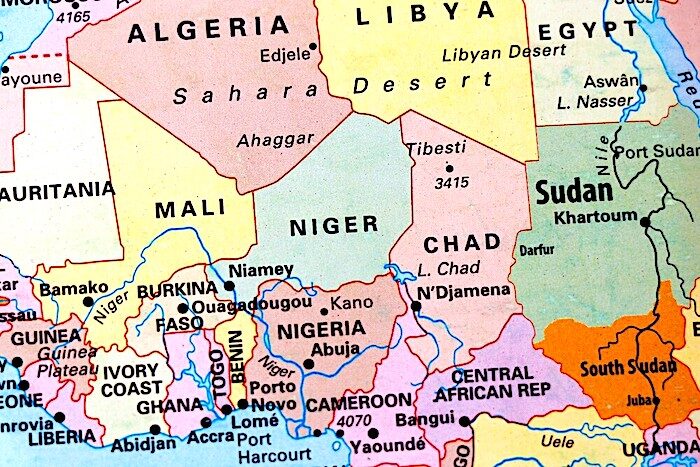

Moreover, the Nigerian military lacks experience in the kind of large-scale ground combat it would be called upon to use to defeat the Nigerien junta. Meanwhile, Niger would be able to draw upon its own modest yet capable military and potentially on forces from Mali and Burkina Faso, which have pledged to treat any Ecowas incursion into Niger as an attack on their own territory.

Lastly, the junta in Niger has enlisted the support of the Russian private military company Wagner, which has considerable major combat experience in Ukraine, Syria and Africa. Logistics might constrain the scope and scale of any Wagner deployment to Niger. But even so, Nigerien military forces loyal to the junta will still be in a far better position to defeat a Nigerian-led Ecowas force than the other way around.

The Consequences of Conflict

From an energy security standpoint, France's reliance upon uranium mined in Niger, which accounts for 20% of French needs, means that any loss of access to uranium sourced from Niger could cause a short-term problem while France finds a replacement source. A conflict in Niger could also put at risk China's near-complete, 100,000 barrel per day oil pipeline linking Niger's fields to Benin, and the further development of oil fields to supply it. Niger produces around 20,000 b/d at present. It would be another nail in the coffin too of the troubled and long-mooted trans-Saharan gas pipeline that proposes to take Nigerian gas to Algeria, for onward exports to Europe.

But the greatest threat to West Africa, the Sahel and Europe will come from the human catastrophe that will befall the region in case of war. In addition to the populations that will be displaced by any outbreak of large-scale fighting, there is a real possibility that an Ecowas-Niger conflict could empower Islamist militants, and minority communities in every nation involved, leading to an outbreak of civil conflict that could take years to resolve, and even then, at the cost of hundreds of thousands of dead and millions of displaced civilians. A regional conflict would unleash a wave of new refugees seeking to cross the Sahel into North Africa and on to Europe, which has already reached a political saturation point when it comes to absorbing migrant populations.

An Ecowas-Niger conflict would also be the death knell for US and European counterterrorism efforts in the Sahel. At a time when the militaries of both the US and its Nato allies are stretched thin due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, the cost of retaining a military foothold in Africa under conditions of war would be prohibitively high. The only exception to this would be if the US and Nato viewed any encroachment of Wagner into the region as unacceptable, triggering a more concerted military engagement that could lead to a proxy superpower conflict in Africa. Such a conflict would only exacerbate the dire consequences of any underlying hostilities between Ecowas and Niger.

About the Author:

Scott Ritter is a former US Marine Corps intelligence officer whose service over a 20-plus-year career included tours of duty in the former Soviet Union implementing arms control agreements, serving on the staff of US Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf during the Gulf War and later as a chief weapons inspector with the UN in Iraq from 1991-98. The views expressed in this article are those of the author.

Looks like it is coup-time in Africa. Today it is Gabon, not too far from Niger. [Link]