Oldowan tools are some of the oldest known in the archaeological record; made of conveniently shaped rocks or crafted from knapped stones, these tools made it possible for hominin species to survive in a hostile world.

Now, a team of researchers have found Oldowan tools in southwestern Kenya that date between to 3 million and 2.58 million years old, broadening the known geographic distribution of this toolkit. They also found hundreds of animal bones as well as teeth of Paranthropus, an early hominin, indicating that the genus Homo may not have been the only sharp tool in the shed. One of the teeth — a molar — is the largest hominin tooth ever found. The findings are published today in Science.

"The Oldowan starts early in East Africa and then it spreads across Africa, and then ultimately leaves Africa and goes all the way to China. It's really the first persistent and widespread technology," said Thomas Plummer, a paleoanthropologist at Queens College and the study's lead author, in a phone call with Gizmodo.

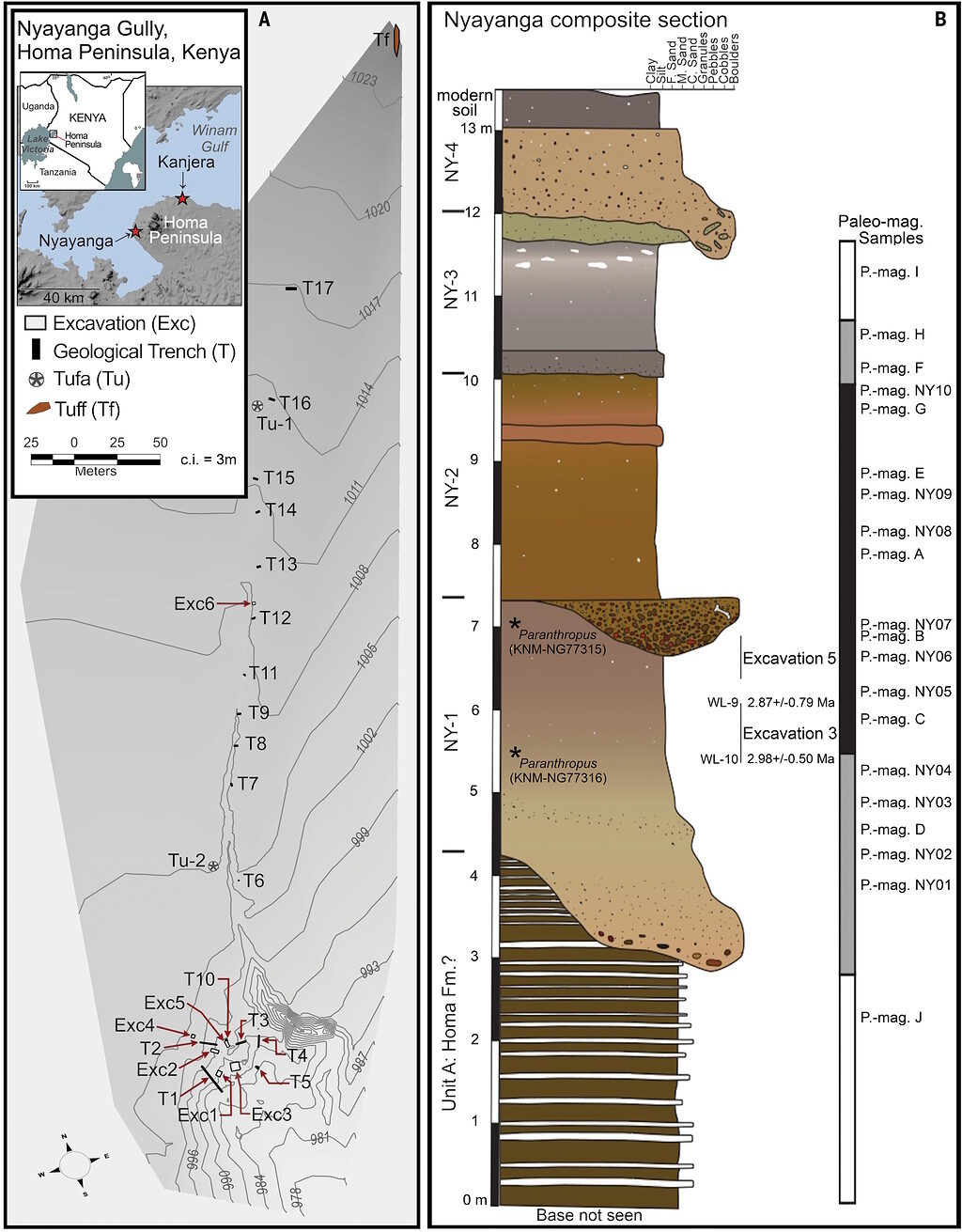

The conservative dating of 3 million to 2.58 million years old comes from magnetostratigraphy, a way of timing sediment deposits to the flipping of the Earth's magnetic field. The Uranium-Thorium dating of apatite crystals in the sediment gave more specific ages of 2.87 ± 0.79 million years and 2.98 ± 0.5 million years, indicating that the site is likely toward the upper limit of the conservative timeframe.

"The assumption among researchers has long been that only the genus Homo, to which humans belong, was capable of making stone tools," said Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, in a Smithsonian release. "But finding Paranthropus alongside these stone tools opens up a fascinating whodunnit."

Paranthropus is an extinct human relative with a broad face and a masticatory set (that is, teeth) built for chewing. Paranthropus had the largest teeth of any primate; though the hominin was smaller than a gorilla, it had larger teeth, Plummer said. Two Paranthropus molars found at Nyayanga are the extent of hominin remains on the site; one of the molars is the largest hominin tooth ever found.

Analyzing the isotopes in the Paranthropus teeth revealed an abundance of a specific carbon isotope indicative of a diet dominated by grasses and herbaceous plants. Other previously discovered hominin remains from around the same time period have also suggested a diet involving those plants (or the animals that consumed them), indicating that our hominin ancestors occupied similar open ecosystems in ancient Africa.

But the hominin diet wasn't vegetarian, as indicated by the finds at Nyayanga. Alongside the Oldowan tools and the Paranthropus teeth were a whopping 1,776 bones found across two excavation sites, both on the eastern shore of Lake Victoria. These included the worked bones of hippos and bovids, and the bones of animals that likely inhabited the local lakeshore environment like turtles, rats, saber-tooth cats, monkeys, and crocodilians.

Some of the hippo and antelope bones had cut marks and evidence of crushing or slicing, indicating that the remains were not only collected at the site but worked by the hominins there. The researchers were unable to identify which hominin species was responsible for the butchering, but the presence of Paranthropus bones is compelling.

The first evidence of fire doesn't appear in the archaeological record until about 400,000 years ago, so the animal meat would presumably have been consumed raw.

The finds at Nyayanga are at least 600,000 years older than other sites that show evidence of butchering megafauna (which hippos certainly are) and plant processing. The researchers note that the Nyayanga finds also predate the increase in brain size that occurred in the genus Homo around 2 million years ago. (That increase in brain size occurred before our species, Homo sapiens, evolved, which is why our nearest cousins, Neanderthals, also had large brain cases.)

"East Africa wasn't a stable cradle for our species' ancestors," Potts said. "It was more of a boiling cauldron of environmental change, with downpours and droughts and a diverse, ever-changing menu of foods."

It was not long ago that we considered Neanderthals backwards and brutish; now, much older remains of Paranthropus are forcing us to consider what other hominins were capable of, and when.

As more sites are interrogated with increasingly advanced methods, we may have a much more nuanced portrait of our history — as well as that of our long-gone relatives — soon.

Reader Comments

Things are A bit rough at the moment being attacked and slandered by a tyrant. The upside is I have been totally freed up and can enjoy hanging out here again. X