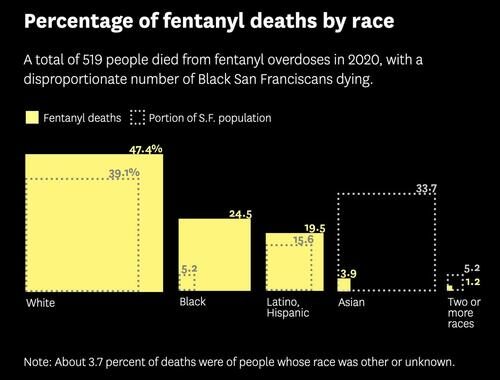

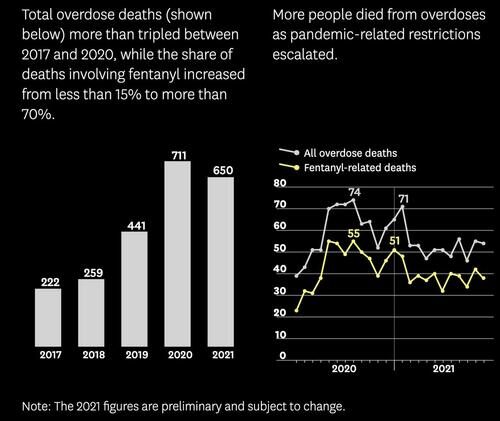

Nearly 3/4ths of the thousands of drug overdoses that have been reported in the City by the Bay have involved fentanyl; for the last two years, fentanyl has been killing far more people in San Francisco than COVID. It's not even close, really.

In San Francisco, roughly 1,310 people died from drug overdoses in 2020 and 2021. That's more than double the roughly 710 people who have died from the virus in the city since the start of the pandemic.

The city's fentanyl death toll would be higher if it wasn't for narcan, the antidote now used more than 500 times a month to yank people back from the brink of death.

Overdose deaths happen all over the city, but by far the biggest concentrations are found within a few square blocks on Tenderloin and South of Market, a part of the city that has long plagued law enforcement.

A large percentage of the older addicts are blacks who have been living on the city's streets for years, if not decades. What's more, the scourge of fentanyl has transformed the Tenderloin into an open-air drug market.

Despite budgeting more than $70M for resources for the indigent last year alone, the city of San Francisco has barely managed to make any kind of positive difference in the lives of the city's homeless. Overdose prevention programs in the last fiscal year alone have accomplished little. And police have been stymied by the progressive DA's insistence that city cops not arrest people.

City leaders have not created a clear, urgent and cohesive plan to intervene despite budgeting $71.4 million for treatment and overdose prevention programs in the last fiscal year alone. Since then, however, the problem has only gotten worse.

While drugs were once smuggled into San Francisco via complex networks of criminals, nowadays, the biggest drug carriers in the city are DHL and USPS.

But the illicit fentanyl now killing people in San Francisco is cooked up in labs — often in China and Mexico — and trafficked via delivery services like UPS and DHL. Doses bound for the city are sometimes mixed with other drugs or fillers, packaged in foil and sold for $20 to $40 a gram.Amazingly, the city's leadership has so far failed to treat the fentanyl crisis with anywhere near the same gravitas as the COVID pandemic.

Despite the death toll, San Francisco leaders have not treated the fentanyl crisis as the all-hands emergency that many residents and advocates recognize.One of the most surprising details from the report is a depiction of an interaction between an SFPD officer and a homeless addict sleeping in a doorway.

The Department of Public Health says that typically, people can access treatment as soon as they're ready. But some of those seeking help, as well as social workers assigned to them, say they commonly wait days, and sometimes weeks, for a bed that meets their needs.

Meanwhile, San Francisco has so far failed to cut the flow of the drug into the Tenderloin and South of Market, where the city has concentrated services and housing for vulnerable people, including those experiencing addiction. Drug dealers operate on the streets with abandon.

As police walk through the Tenderloin, Sgt. Heather Fegan approaches a woman slumped in a doorway.It seems the only thing officers are empowered to do when dealing with SF's population of homeless drug addicts is revive them with Narcan when they overdose. On particularly bad days, police in the Tenderloin revive up to 10 or a dozen people, sometimes returning to the same individual just hours later.

"It's San Francisco police, honey," Fegan says. Another officer gently taps the woman's shoulder, rousing her awake. "We're just making sure you're all right," the officer says. "You're not in trouble or anything."

Still, police usually don't make arrests when they find people dying from an overdose, nor do they investigate to try and ascertain where the drugs came from.

Who's decision was this? Well, unsurprisingly, the Chronicle lays the blame at the feet of Chesa Boudin, the San Francisco DA facing a recall election because of his notoriously soft on crime (critics call them 'pro-criminal') policies.

There's also Mayor London Breed, who has apparently ordered police to "get tough" on crime - at least, that's what she's telling the public. On the street, it doesn't seem like much has changed.

Mayor London Breed's new get-tough public stance is consistent with her longtime views, but still marks a shift from programs she spent much of the last year championing, which aim to reduce police interactions with people in need of mental health care and addiction treatment.Somehow, progressive do-gooders like Boudin and Breed have embraced the idea that the 'broken windows'-style tactics used in the 1980s to clean up NYC simply aren't effective. Progressives have taken another view: that the welfare of criminals and drug addicts should be prioritized above all else.

"It's time that the reign of criminals who are destroying our city...come to an end," the mayor said, adding that San Francisco should be "less tolerant of all the bulls — ."

One common saying is "kilos, not crumbs".

Police Chief Bill Scott and District Attorney Chesa Boudin agree, though, that the city cannot focus on arresting and prosecuting users or lower-level drug dealers, some of whom are supporting their own addictions. Boudin, who faces a recall election this year fueled by critics who say his policies are too lenient, says it's not effective to prosecute quality-of-life crimes, including street drug use, and favors seizing "kilos, not crumbs" of narcotics.The problem with this 'treatment first' narrative is that drug addiction treatment in the US is notoriously expensive. It involves rehabs, medication, outpatient therapy. It's a lot. And most of the time, it doesn't work. For more thoughts on why treatment often isn't enough, click here.

As priorities have shifted, the city police force presented about 40% fewer drug-related arrests to the D.A.'s office in 2021 than in 2019, according to data obtained by The Chronicle. But the cases that police still bring are more serious — and Boudin is more frequently filing charges. Even so, Boudin acknowledges that the Tenderloin "has not gotten better."

"We need it to be easier for people to get help than it is to get high," he said.

But at least Big Pharmaceutical companies are lining their pockets while progressive politicians are building a new indomitable political machine.

Comment: See also: