Yesterday it was social psychology. Today it's marine biology. Tomorrow, could it be Canadian history and the rest of society?

The sciences are currently grappling with a significant loss of credibility that has been called the "replication crisis." This crisis stems from a widening recognition that many published academic findings - including foundational work in some disciplines - cannot be replicated and, accordingly, cannot be independently verified. Both of these conditions are key elements of the modern scientific method. As a result, many well-cited scientific works long considered to reveal important truths are now considered unreliable or hopelessly biased. Some are the product of outright fraud. A recent example with a strong Canadian connection illustrates the problem.

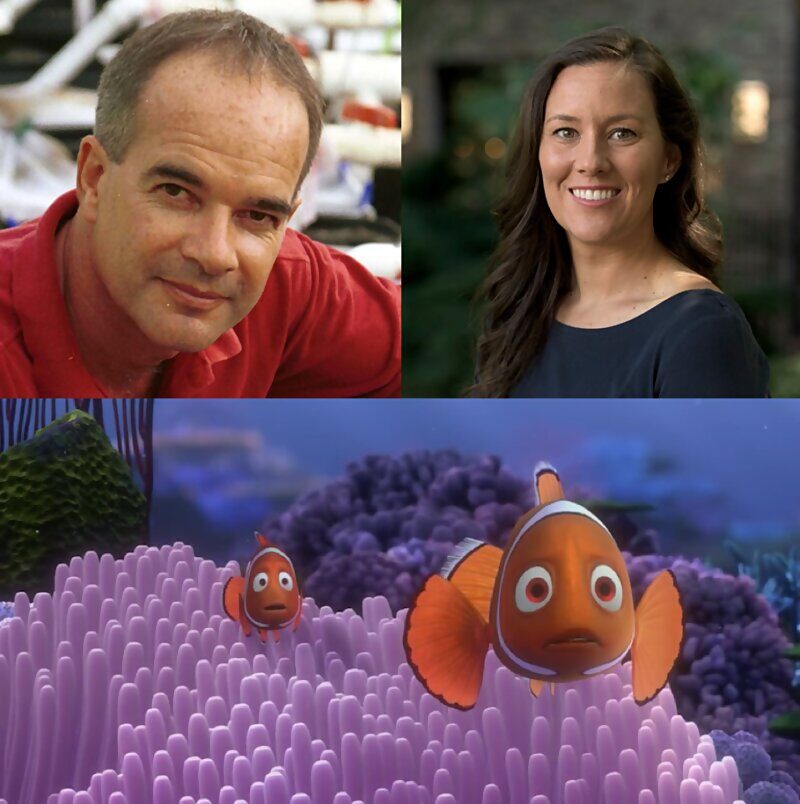

Since 2009, numerous academic publications by marine biologists Philip Munday of Australia's James Cook University and Danielle Dixson of the University of Delaware have asserted that climate change will alter the behaviour of tropical fish in troubling ways. The pair's many experiments claimed to show that increased acidity in the oceans resulting from rising CO2 levels will cause various Pacific Ocean species to gradually lose their ability to flee predators and find their way home. The afflicted species include the orange clownfish, popular for its role in the Disney movie Finding Nemo.

But was any of it true?

Intrigued by the calamitous results, in 2014 an international team with a large Canadian component assembled at the same Great Barrier Reef laboratory frequented by Munday and Dixson to try to understand the underlying biology behind these changes. "The behavioural effects in those original papers were some of the most phenomenally profound effects I'd ever seen in fish behaviour," recalls team member Graham Raby, a biology professor at Trent University in Peterborough. "Our intention was to build on that existing research and figure out the physiological mechanisms at work."

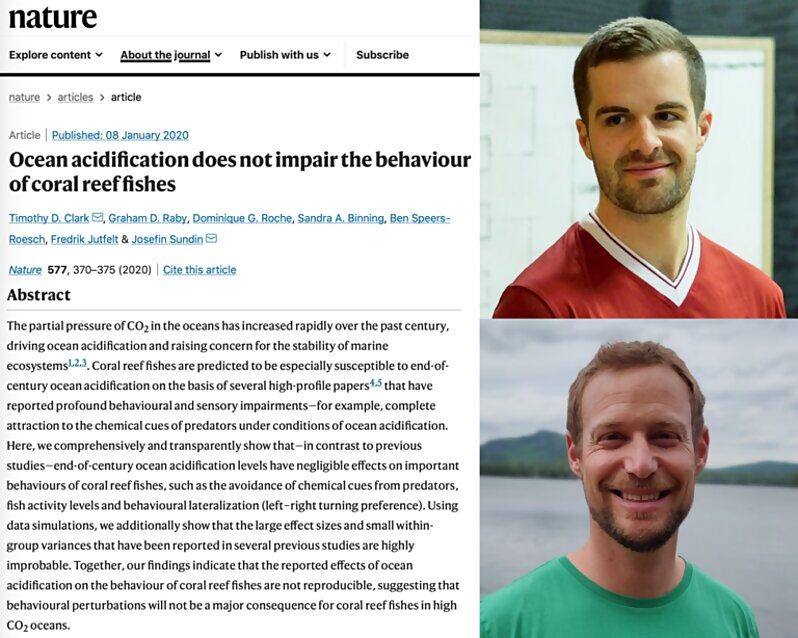

But despite repeated attempts at replicating Munday and Dixson's work, the team produced only null results. "We couldn't find any evidence of behavioural effects of ocean acidification," Raby says in an interview. Another team member, Dominique Roche, a researcher based at Carleton University in Ottawa and Université de Neuchâtel in Switzerland, notes that in hindsight the entire thesis never even made much sense. That's because at night coral reefs already emit levels of CO2 similar to what Munday and Dixson were warning about far into the future. "And the fish sleep inside the reefs," observes Roche. If rising levels of CO2 were going to change the behaviour of fish, it should already be evident.

After several years of meticulously documented research, in 2020 the seven-member team, including Raby and Roche, published a comprehensive refutation of the "Crazy Nemo" thesis in the prestigious science journal Nature. Some of the team went further and requested various international funding bodies investigate Munday and Dixson for academic misconduct since their work contained statistical anomalies generally associated with data fraud. "There are irregularities in the data that need to be investigated," states Roche firmly.

Cruel or not, that a scientific finding enjoying broad public support and with significant public policy implications could not be repeated by independent researchers is a very serious matter, and a major blow to the entire field of marine biology. Everyone (save for the replication team) appeared so eager to accept a novel new story that bolstered popular beliefs about climate change that they failed to ask whether the results were even true. And when the findings proved unreliable, it was the truth-tellers who had to face a hostile crowd.

Despite the personal attacks and reputational damage suffered by marine biology, however, Raby firmly considers the refutation process to be "a good news story." Why? Because something that was mistakenly considered to be fact and widely publicized as such was eventually disproven through scrupulous adherence to the basic principles of the scientific method. By trying and failing to repeat the Crazy Nemo experiments, the team eliminated a falsehood and, in doing so, improved their discipline's knowledge base.

It is a clear demonstration of the vital process of conjecture and refutation. "As awareness of the replication crisis spreads across scientific fields, it is making them all more rigorous," says Raby optimistically. "This is an illustration of how science corrects itself. And science is the only method we have to find the right answers." Could such a commitment to skeptical inquiry fix the rest of society as well?

The Rise of the Replication Crisis

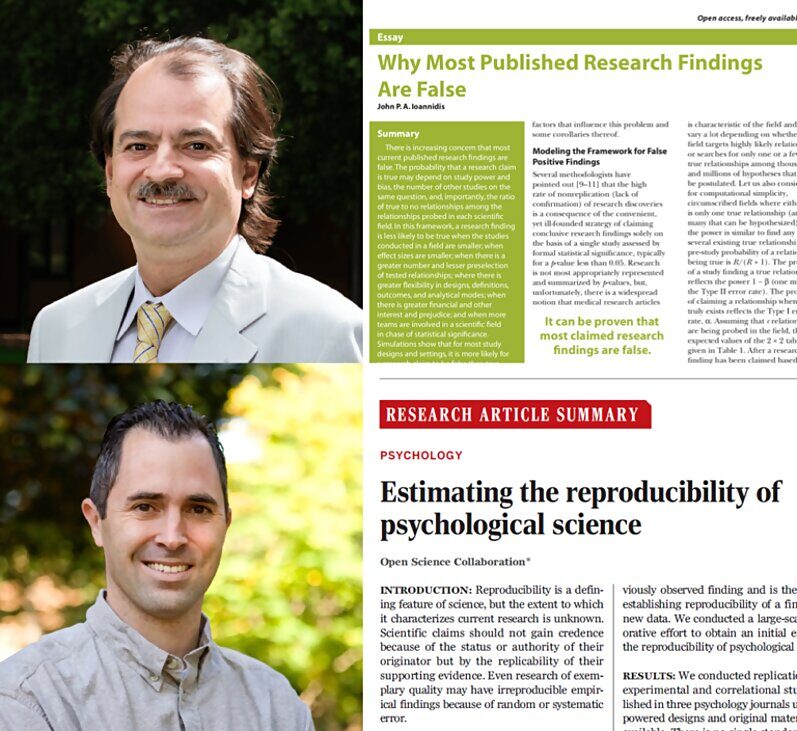

The phenomenon of the replication crisis is generally considered to have been first identified in a 2005 essay by Stanford University epidemiologist John P.A. Ioaniddis provocatively titled "Why Most Published Research Findings are False." Ioaniddis, well-known today as an outspoken critic of Covid-19 lockdowns and other pandemic policy mistakes, built his argument on the dubious incentive structure involved in the academic publishing process. Rather than revealing universal truths, Ioannidis figured much of what passes for academic research is simply an "accurate measure of the prevailing bias."

Shocked by these results, Nosek and other academics quickly embarked on further tests of the reliability of published results in other social sciences. The results were similarly disappointing. Large swaths of original experiments could not be replicated, or the size of the claimed results proved far less than first reported. Since 2015 nearly every discipline in the natural and social sciences - from biomedicine to political science to economics to obstetrics to ophthalmology - has suffered a reputational blow as a result of disproven or unrepeatable results. Marine biology is just the most recent example of how far the rot has spread.

A common theme among some of the highest-profile examples is that adherence to popular political objectives or storylines can often facilitate or provide cover for faulty research. The Crazy Nemo thesis' relationship to global warming is an obvious example.

Another stems from well-publicized research by American criminologist Eric Stewart of Florida State University, who claimed perceptions among white residents of black people were linked to historical evidence of racial violence. Stewart (who is black) said his polling data showed white people living in southern U.S. counties where lynchings had occurred in the past were more likely to consider black people a present-day threat and demand a harsher criminal justice system, than those living elsewhere. Such a finding obviously fits neatly with current claims of systemic racism. Yet Stewart's co-authors (who are white) later discovered the findings were based on phony poll results Stewart had supplied; the papers were soon retracted. Stewart responded to this scandal with the nasty, if predictable, accusation that his co-authors "essentially lynched me and my academic character."

In another example, this time from political science, published research by graduate student Michael LaCour at UCLA claimed it was possible to permanently alter the opinions of straight people about gay marriage by having gay canvassers talk to them at their front door. This was widely reported and enthusiastically hailed. It was subsequently revealed that LaCour had simply made up the data to satisfy his own interests. With few academic journals requiring that authors provide access to their raw empirical data, such deceptions can be despairingly easy to perpetrate.

Social Psychology: "Morality in an Experimental Idiom"

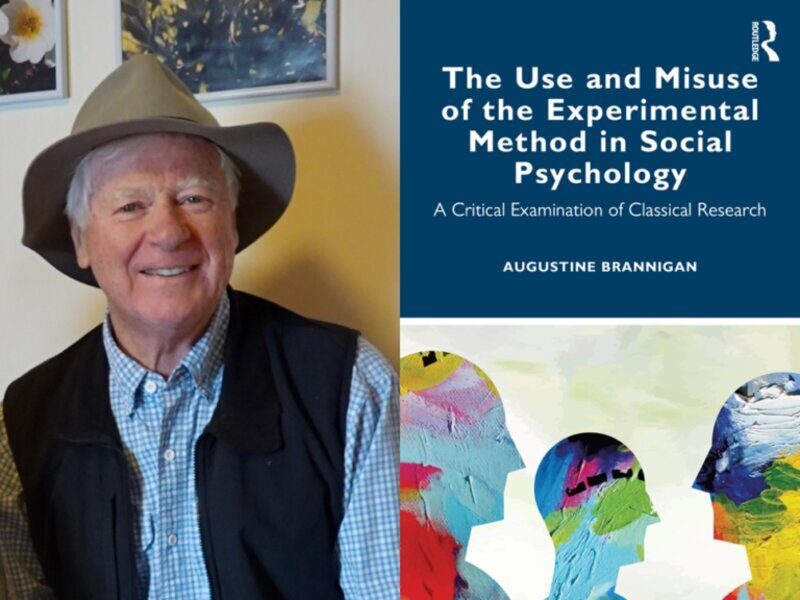

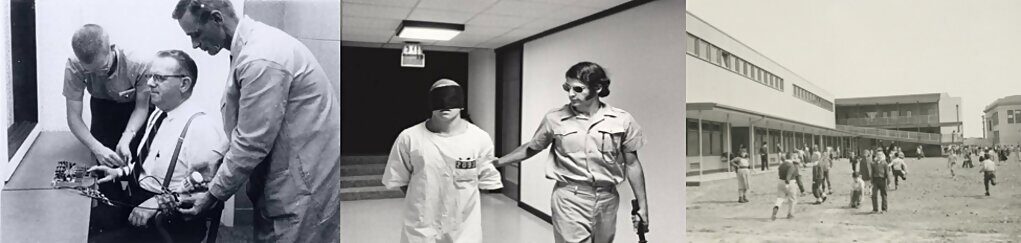

Perhaps no discipline has been hit harder by the replication crisis than social psychology. It featured prominently in Nosek's landmark 2015 study and now some of its most famous research is coming under similar scrutiny. Augustine Brannigan is professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Calgary and author of the 2021 book The Use and Misuse of the Experimental Method in Social Psychology: A Critical Examination of Classical Research. In it, Brannigan lays out numerous and convincing reasons to be deeply skeptical of some of the field's best-known research, including iconic studies such as Yale University professor Stanley Milgram's famous obedience experiment, the Stanford Prison Experiment and the Pygmalion Effect.

In the 1960s, Milgram claimed to show how ordinary people could be complicit in horrific crimes by having subjects administer progressively greater electric shocks to "students" during what they were told was a test of new learning methods. In reality, the "students" were actors only pretending to be shocked; the real test was whether the subjects would keep raising the shock level when told to do so by an authority figure. Milgram said his experiment was inspired by the trial of Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, and offered insight into how ordinary German citizens willingly tolerated and even abetted the Holocaust.

Then there's the Pygmalion Effect arising from a series of experiments in the 1960s at Spruce Elementary School in San Francisco that purported to show how teachers graded students based on their own expectations and prejudices, rather than demonstrated ability. This was accomplished by tricking teachers into believing some of their students had been identified as having exceptional abilities. These findings, which carried strong racial implications, were central to the school busing debate in the U.S. in the 1970s and continue to wield significant influence over school policy today, especially since they appear to prove the pervasiveness of racism throughout the school system.

"They are all very entertaining studies, and they ask some really interesting questions," admits Brannigan. These dramatic "high-impact" experiments are also hugely influential, occupying large sections of undergraduate textbooks and representing the very foundations of the field. "But as science, they're terrible," Brannigan says. "Much of what passes for science in social psychology is just morality in an experimental idiom." Asked what such a revelation might mean for the future of the discipline, he retorts, "If the entire field were to disappear overnight, I don't think the world would be any worse for it."

Let a Thousand Replication Crises Bloom

If there's an overarching message arising from the replication crisis beyond the fate of social psychology, it's that relentlessly questioning all scientific work is the most effective cure for bad science. This includes scrutinizing new and flashy claims as soon as they are unveiled as well as re-evaluating long-accepted ideas that have already gained status as scientific certainty. Along with renewed emphasis on tough and unsentimental scientific replication must also come more rigorous fact-checking by scientific journals and a less chummy attitude towards the peer review process, with more emphasis on "review" and less on "peer."

"No science is immune to these challenges," says psychologist Nosek, who now heads up the Center for Open Science. Beyond requiring greater transparency in data and research methodologies, he says the best defence against phony or unreliable results is to ensure that skepticism is placed at the centre of all scientific inquiry. "If we don't have a system that is self-skeptical and questions existing findings, then we will create a world that is built, more and more, on false confidence," he says in an interview. Everything must be tested and tested again, regardless of how much that may threaten existing beliefs or comfortable political viewpoints. "Even the replications need to be replicated," Nosek states. "It all needs to be treated with skepticism."

Patrice Dutil teaches public administration and political science at Toronto's Ryerson University, although much of his academic research involves Canadian history. He worries the humanities are currently suffering from the same ideological myopia and bad research habits that characterize the replication crisis. Of course, history differs in many significant ways from sciences such as social psychology or marine biology, Dutil admits. There are no experiments to replicate or reams of data to test, and much of the published work consists of subjective interpretations of readily available evidence. "Beyond ensuring our footnotes are in order, there aren't a lot of numbers to crunch," Dutil notes wryly. Nonetheless, he argues, skepticism remains critical to good scholarship.

Dutil points to his own institution's plan for a name change as a prime example of the need for history to experience its own replication crisis. A report from a school committee recently recommended that 19th century educator Egerton Ryerson's name be removed from the school due to his alleged role in creating Canada's Indian Residential School system, a demand readily accepted by school leadership. "This entire episode represents a wholesale misrepresentation of historical facts," Dutil says. "Nothing the [committee's] report says is verifiable. In fact, its interpretations of Ryerson are plain wrong."

According to Dutil, "Ryerson is being 'hanged' because of a five-page letter," referring to a brief report Ryerson wrote in 1847 sketching out a proposed national schooling system for natives. Most of this short document is based on Ryerson's observations about a philanthropic school for poor children in Hofwyl, Switzerland. It would be another four decades before the federal government created a comprehensive national system for native education — and it looked nothing like the Hofwyl school.

In another example of how Canadian history is plagued by unverifiable claims, Dutil points to the July 1 statement from the Canadian Historical Association claiming a "broad consensus" for the notion that this country is guilty of genocide in its policies towards Indigenous people. Borrowing from the language of the replication crisis, Dutil argues, "This is emphatically not a settled issue. Such a claim would have to rest on verifiable evidence, and that does not exist. To say such a thing is true is a gross abuse of authority."

Yet the genocide story is quickly becoming an unquestioned - and almost unquestionable - belief across Canadian society. In British Columbia, for example, social media commentator Aaron Gunn saw his plans to run for the leadership of the B.C. Liberal Party stymied by a party committee that claimed his candidacy would be "inconsistent" with the party's values. As evidence, the committee cited Twitter posts addressing Indigenous issues in which Gunn complained about the use of "a loaded word like 'genocide' that doesn't remotely reflect the reality of what happened."

Anyone who declares themselves skeptical of claims of a Canadian "genocide" is now at risk of cancellation. But once any topic is declared off-limits in this way, it becomes impossible to test its underlying assumptions and claims. Such a closed system inevitably gives shelter to falsehoods and misinformation. Despite the important lessons of the replication crisis, skeptical inquiry is actually becoming increasingly rarer outside the sciences.

The Need for Universal Skepticism

In 2018 Dutch academics Rik Peels and Lex Bouter proposed the "desirability of replication in the humanities," and sketched out a system by which research in politics, history, linguistics or literature could be subjected to the same rigorous efforts now familiar to the sciences in order to weed out phony or unreliable claims. If their goal was to start a movement, however, Peels and Bouter appear to have failed.

And the pandemic is making things worse. In a recent essay for the online magazine Knowable, entitled "Question the 'lab leak' theory. But don't call it a conspiracy," Retraction Watch's Oransky notes that honest skepticism has often been dismissed and discounted as partisan posturing by political opponents throughout the Covid-19 era. At a moment when we should be honouring the scientific method, we are instead experiencing an unscientific rush to judgement across many important issues.

"In the last 18 months...practically no one could have a dispassionate discussion of the evidence - or lack thereof - for using various older drugs, usually approved to treat parasites, against Covid-19. Such discussion frequently escalated into screaming matches between polarized opposites. If you ever made a comment that could be interpreted as saying that Donald Trump was not wrong about absolutely everything - including his boosting of one such drug, hydroxychloroquine - you were clearly promoting the drug because you were partisan. If you dismissed the drug, surely you were a partisan on the other side."Polarization of this sort is clearly inimical to the scientific method - and, indeed, to all forms of research and open intellectual inquiry - as it presupposes the answers before the questions can be asked and any claims tested. The best solution in all cases is to simply let open inquiry do its work. And until it supplies a reliable answer, it is foolish and dangerous to limit debate or attack honest skepticism.

Drawing this line is important if we want to bring clarity to important public policy issues. Healthy skepticism seeks to test what we think we know in order to improve confidence in the facts we must rely upon - and to root out malfeasance, incompetence and fraud. Cynicism, on the other hand, tends to disregard all knowledge and expertise as a matter of habit. At a time when absolute certainty is very much in vogue and any dissent treated with disdain - on charged topics as varied as gender identity and biology, racism, meritocracy, addiction, criminal justice, sexual violence and all the other fault lines that define our current cultural revolution - we need more of the former and less of the latter. It should be possible to raise important questions without being accused of being cynically anti-science or threatening public order.

"A return to scientific, or sobering, skepticism is necessary," Brannigan says. "We must learn to be suspicious of all findings generally, and to be even more suspicious of findings that seem too good to be true, or blow in the right directions." As the replication crisis has shown, dearly-held scientific facts can often turn out to be unscientific myths when subjected to the appropriate scrutiny. But why should such a standard be reserved for the sciences alone? If we seek to know what is true, every academic discipline and area of public policy debate should bear the same burden of proof. Take nothing for granted.

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior features editor of C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

Reader Comments

(No disrespect meant to the original.)

God meant us to ask questions and experiment; Become our own scientist. I used to think (naively) that once you finished school learning was done. Wrong. I will be asking questions and experimenting for all this life and beyond into the after life.

Even though he's spitting in the wind, the effort is worthwhile since without any pushback the deceit would be completely unchecked and worse. Maybe he's doing all anybody could given the terrain.