As with many everyday objects, it is difficult to determine who invented glasses, or where and when they were first used. In fact, they were not really "invented" in the sense of being a great discovery, a unique inspiration that provided a solution to a hitherto unanswered problem. It was more of a gradual process that went hand in hand with other scientific and technical discoveries — accompanied by persistent speculation and questions. In prehistoric times the Inuit apparently used a sort of protective eyewear made of walrus ivory against snow blindness. And among the unanswered questions from those early times is the matter of Nero's emerald. Pliny the Elder wrote in his c. 77 Natural History that Emperor Nero held an emerald to his eye to observe gladiator contests: "The princeps Nero viewed the combats of the gladiators in a smaragdus." Pliny used the term smaragdus for a variety of green minerals and made several observations about the soothing effects of green gemstones.

This was thought for a long time to be the first evidence of the use of a precious stone as a vision aid. But as Nero is said to have been long-sighted, the stone would not have helped him to see more clearly. And as Pliny speaks of a "flat emerald," in other words an uncut stone, it cannot have improved vision. Nero's use of such a gemstone would have neutralized the glare of the sun. Pliny's allegation has become a famous anecdote and is routinely cited by historians of science and technology. As the German Enlightenment writer Gotthold Ephraim Lessing explains in his Forty-Fifth Letter, Nero is more likely to have used it "because of the pleasant green color for the eye," to protect him from the sun's glare. Nero's emerald is not the original corrective lens but at best a remote precursor of modern-day sunglasses.

In chapter 6 of the first book of his Natural Questions (62-63), Seneca described an aid to vision — albeit an impractical one: "Letters, however small and dim, are comparatively large and distinct when seen through a glass globe filled with water." The fact that this observation was not followed up had to do with Seneca's assumption that the magnifying effect was produced by the water rather than the glass.

In his book Kitāb al-Manāẓir (Book of Optics), written in 1021, the Arab mathematician Ibn al-Haytham, also known as Alhazen, was the first to recognize and describe the magnifying property of curved glass surfaces and to put it to practical use by making reading globes. Despite the groundbreaking significance of this discovery, it remained unknown in the West for a long time because it was published in a treatise written in Arabic. It was not until the end of the twelfth century that Alhazen's treatise was translated into Latin by Franciscan monks in Italy, revealing to the Western world that an object was magnified when viewed through a transparent spherical element. The translation of the Book of Optics provided not only a physical explanation but a practical insight: convex polished hemispheres made of certain semiprecious stones magnified letters when placed on them. These reading stones were the first vision aids to be used systematically.

When Alhazen's writing became known in academic circles, the Oxford scholar Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294) was one of the first to recognize the practical utility of spheres as reading aids and to understand that colorless glass would be ideal for making them. At the time, however, it was only possible to make colored glass — except in Venice and Murano, where the manufacturing process was a carefully guarded secret.

Reading spheres were therefore cut from quartz, rock crystal, or beryl, which had a particularly strong magnifying effect. Beryl is a common mineral, more accurately a silicate, with hexagonal crystals. It was said to have magic and healing powers, strengthening belief in God and working against poisons. Beryl was one of the precious stones used in the foundations of the Jerusalem city walls. It comes in different colors but it can also be colorless and almost transparent. It was this property that made it ideal in the Middle Ages as a reading aid. The plano-convex slabs of beryl called lapides ad legendum, reading stones, were placed with the flat side on the page of the book so as to enlarge the letters.

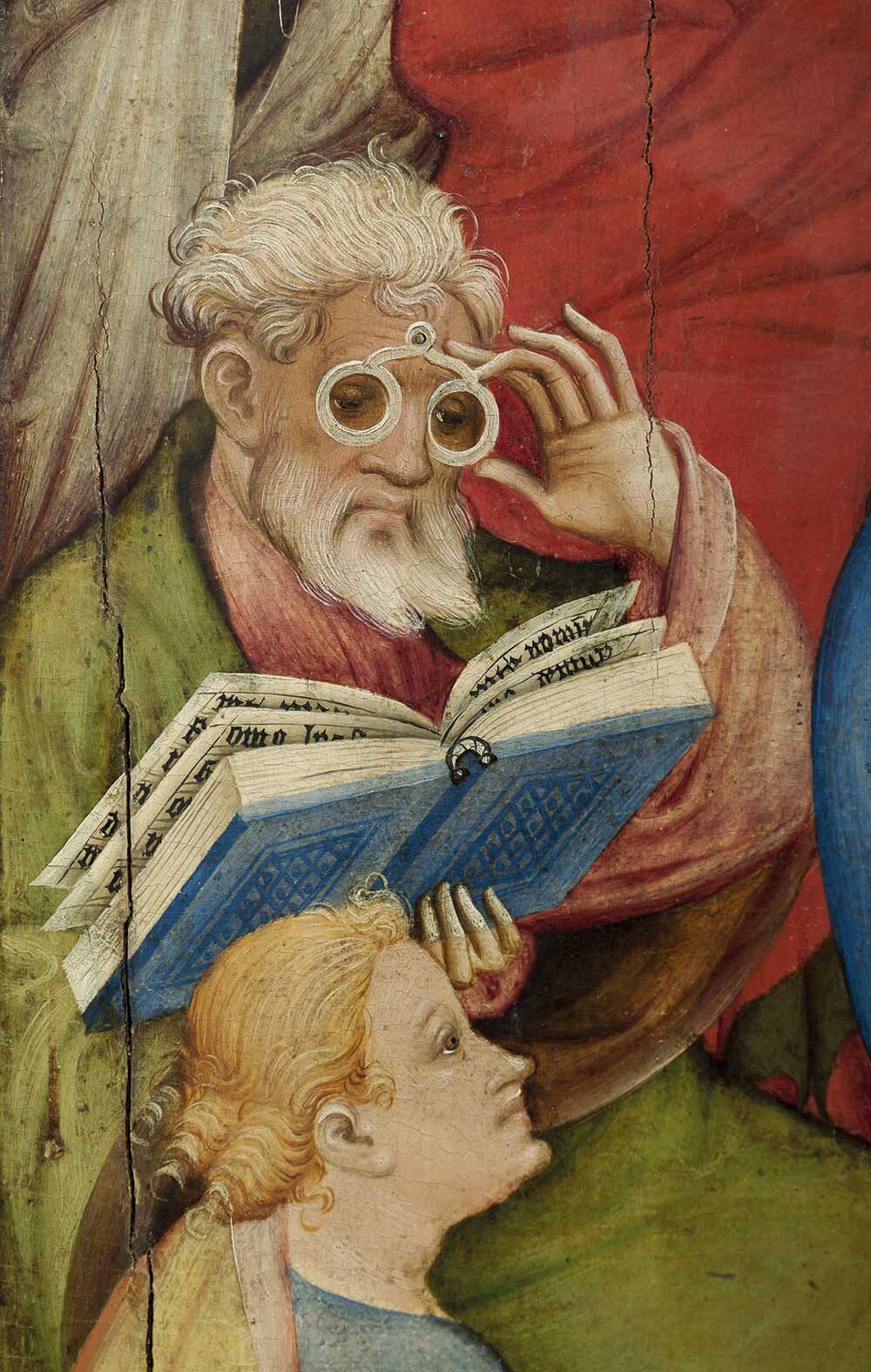

The only illustration of reading stones is thought to be on the fifteenth-century altar of the Premonstratensian Wilten Monastery in Tyrol. One of the altar wings shows Saint Odile, the patron saint of the blind or partially sighted. Franz Daxecker, a professor at Innsbruck Eye Hospital, discovered that the painter had replaced her usual attribute, a pair of eyes often placed on a book, with reading stones held over an open book so as to magnify the letters underneath.

A short time later, beryl is also mentioned in the panegyric of Die goldene Schmiede (The Golden Smith) by Konrad of Würzburg (1277-1287). Here, too, its natural magnifying property is described, this time with an allusion to the Virgin Mary, who magnified sinners' sins and motivated them to repent.

Thus, in the Middle Ages, beryl was also supposed to possess the power to bring about change. Apart from the supposed magical effect, the practical use of beryl is also mentioned. In his manuscript Lilium medicinae, Bernard de Gordon, a French doctor and professor at the University of Montpellier, described many diseases and their possible treatment, together with the then recently discovered "eyes made of beryl," which made it possible to read and study even at a very old age.

Reading stones were used initially to assist the elderly with failing eyesight, but they spread quickly as a reading aid for younger people. They also became more widespread as poor eyesight, particularly in the aged, was no longer seen as a disease to be treated but rather as an impairment that could be overcome with technical aids. In his 1363 work Chirurgia magna, for example, a compendium of the medical and surgical knowledge of the time, the French physician Guy de Chauliac recommended various tinctures against poor eyesight. He was one of the first surgeons to operate on cataracts, ultimately stating: "If that does not help, the patient must use lenses made of beryl or glass."

Until around the end of the thirteenth century, beryl remained the most commonly used material for reading stones, although the Latin beryllus and the Middle High German Berille were employed as an umbrella term for all transparent, shiny crystals — hence the French verb briller, meaning "to shine."

Excerpted from In the Blink of an Eye: A Cultural History of Spectacles by Stefana Sabin, published in English translation by Reaktion Books Ltd. English translation by Nick Somers. English translation © Reaktion Books 2021. All rights reserved. First published in German as AugenBlicke. Eine Kulturgeschichte der Brille, © Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2019.

Reader Comments