The invention of clothing, and the development of the tools needed to create it, are milestones in the story of humanity. Not only are they indicative of strides in cultural and cognitive evolution, archaeologists also believe they were essential in enabling early humans to expand their niche from Pleistocene Africa into new environments with new ecological challenges. However, as furs and other organic materials used to make clothing are unlikely to be preserved in the archaeological record, the origin of clothing is still poorly understood.

The current study published this week in iScience, which reports on a worked bone assemblage found near the Atlantic Coast of Morocco, provides strong evidence for the manufacture of clothing as far back as 120,000 years ago.

As part of her research with the Institute of Human Origins and the Lise Meitner Pan-African Evolution Research Group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH), Hallett was studying the vertebrate remains from Contrebandiers Cave deposits dating from 120,000 to 90,000 years ago.

"The Contrebandiers assemblage now replaces Blombos as the oldest bone tool assemblage and industry," said Marean, who is associate director with the ASU Institute of Human Origins and Foundation Professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, as well as honorary professor and international deputy director at the African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, Nelson Mandela University.

"This was a critical time period and location for the early members of our species," said Hallett, "and I was primarily interested in reconstructing the diet and habitat niche of the people who used this cave."

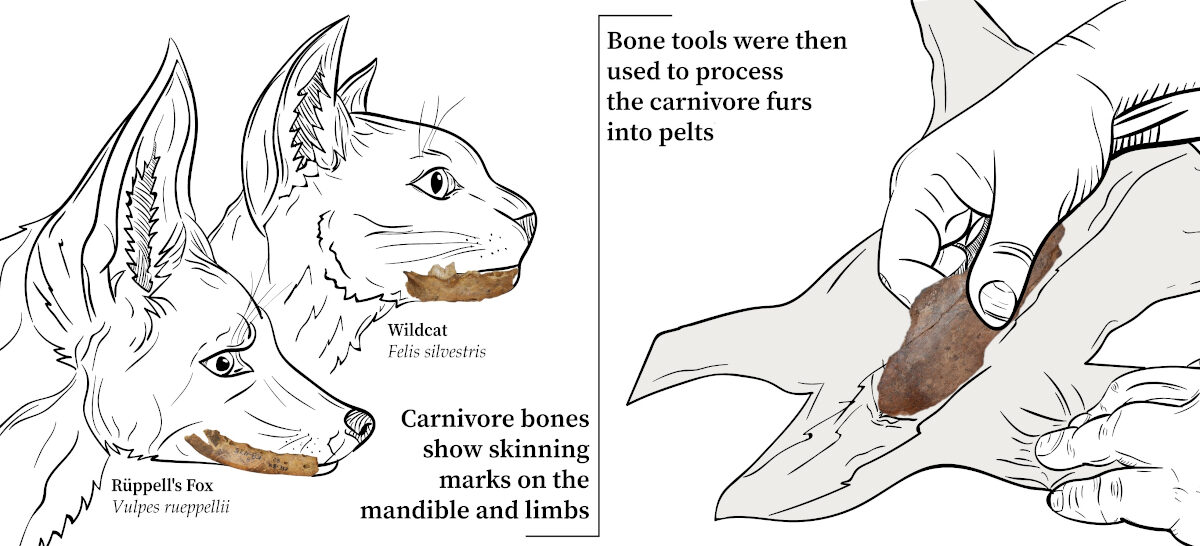

Among the roughly 12,000 bone fragments, Hallett found more than 60 animal bones that had been shaped by humans for use as tools. At the same time, Hallett identified a pattern of cut marks on the carnivore bones suggesting that, rather than processing them for meat, the occupants of Contrebandiers Cave were skinning them for fur.

Hallett compared the tools she identified with others in the archaeological record and found that they had the same shapes and use marks as leather working tools described by other researchers.

"The combination of carnivore bones with skinning marks and bone tools likely used for fur processing provide highly suggestive proxy evidence for the earliest clothing in the archaeological record," Hallett said. "But given the level of specialization in this assemblage, these tools are likely part of a larger tradition with earlier examples that haven't yet been found."

Also hidden amongst the bone fragments was the tip of a tooth from a whale or dolphin bearing marks consistent with use as a pressure flaker — a tool used for shaping stone tools. Given the age of the find, this represents the earliest documented use of a marine mammal tooth by humans and the only verified marine mammal remain from the Pleistocene of North Africa.

"Once again, we see that complex technologies such as bone tools are only associated with aquatic adaptations at the origin point of modern humans," Marean said. "The coast was crucial."

"The Contrebandiers Cave bone tools demonstrate that by roughly 120,000 years ago, Homo sapiens began to intensify the use of bone to make formal tools and use them for specific tasks, including leather and fur working," Hallett said. "This versatility appears to be at the root of our species and not a characteristic that emerged after expansions into Eurasia."

In the future, Hallett hopes to collaborate with other researchers to identify comparable skinning patterns in the assemblages they study and gain a better understanding of the origins and diffusion of this behavior.

Published article: "A worked bone assemblage from 120,000-90,000 year old deposits at Contrebandiers Cave, Atlantic Coast, Morocco." iScience. Emily Yuko Hallett, Curtis W. Marean, Teresa E. Steele, Esteban Álvarez-Fernández, Zenobia Jacobs, Jacopo Niccolò Cerasoni, Vera Aldeias, Eleanor M.L. Scerri, Deborah I. Olszewski, Mohamed Abdeljalil El Hajraoui, Harold L. Dibble.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter