The research, which was published Nov. 11 in the journal Nature, examined the rate that these storms "decay," or weaken, by analyzing historical intensity data for storms that made landfall over North America from 1967 to 2018. The paper's authors cited a rise in ocean temperatures amid a warming climate as the key factor behind the trend.

The study was conducted by researchers Lin Li and Pinaki Chakraborty, both of whom work at Japan's Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology. According to Nature, the study authors found "a significant long-term shift towards slower decay," which allows storms to maintain a higher intensity over land for a longer time period. This slower period of decay was said to align "with a long-term regional mean sea surface temperature over the Gulf of Mexico and the western Caribbean, which are adjacent to land and supply the moisture for the storms before landfall."

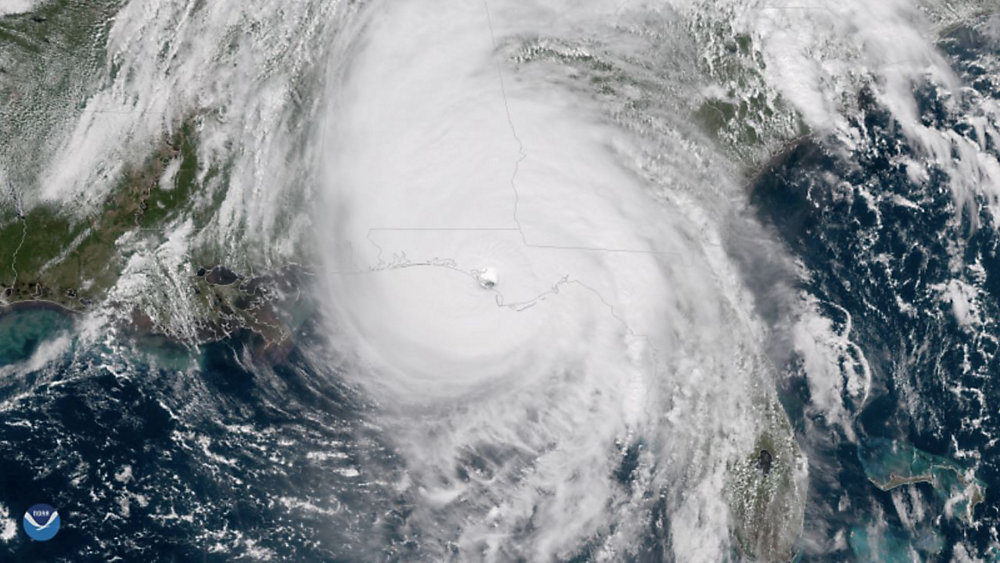

Hurricane Michael made landfall near Mexico Beach, Florida, on Oct. 10, 2018. A post-season analysis revealed that Michael was a Category 5 storm when it struck Florida.

In their research, Li and Chakraborty used the loss of storm intensity over a period of 24 hours after landfall to define a proper timescale for each hurricane they examined. They found that a typical hurricane in the 1960s lost about 75 percent of its intensity in the first day past landfall. Today, that number is down to about 50 percent.

"This is a huge increase," Chakraborty told The Associated Press. "There's been a huge slowdown in the decay of hurricanes."

AccuWeather lead tropical expert Dan Kottlowski, who has been with the company for more than four decades, said he's been noticing through the years that once a hurricane or tropical storm makes landfall, they seem to linger longer.

"I think due to the increased oceanic heat content and overall warm waters, hurricanes might have a more robust and consistent moisture profile," said Kottlowski, who read the study but was not involved in the research. "This will have to be studied more closely, but the hypothesis being proposed here seems logical."

Tropical storms or hurricanes weaken as they move over land in part because they no longer feed on warm ocean waters that serve as their primary energy source. According to Nature, the researchers looked for a "physical explanation" for why a warming climate can cause slower decay in tropical systems. Even after a hurricane moves away from the ocean, it retains enough moisture content to act as a secondary, smaller energy source.

To support their findings, the researchers performed hurricane landfall experiments through a state-of-the-art atmospheric model. Li and Chakraborty used the computer simulation to show that higher sea surface temperatures can increase the amount of moisture a hurricane carries, thus resulting in slower storm decay.

One potential problem that Kottlowski pointed out with the research was data bias due to improvements in weather forecasting technology and improved satellite tracking.

Kottlowski noted that the methods and data used by the researchers look pretty convincing, but he cautioned that more research is necessary going forward.

Colorado State University meteorologist Phil Klotzbach, who specializes in seasonal forecasts for hurricanes in the Atlantic basin, also read the study and said the approach the authors used seemed "reasonable."

He also noted that the modeling component they used for their physical argument, the increase in storm moisture that's driven by the rise in sea surface temperature, which leads to the slower weakening of tropical cyclones at landfall, was "convincing."

"I really like this paper and the approach that they used. It's always good to see more work being done on inland decay, as that area has tended to be a less-studied area compared with [storm] intensification," Klotzbach told AccuWeather.

The implications for hurricanes staying stronger over land now means cities farther inland could be at greater risk as storms unleash destructive winds and inundating rain. It could also have ramifications when it comes to insurance rates and building codes.

"If [the researchers'] conclusions are sound, which they seem to be, then at least in the Atlantic, one could argue that insurance rates need to start going up and building codes need to be improved ... to compensate for this additional wind and water destructive power reaching farther inland," Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher with the University of Miami who was not involved with the study, told the AP.

Chakraborty noted to the AP that Atlanta is an example of an inland city that could face more damage from a longer-lasting storm. Just last month, the city's mayor, Keisha Lance Bottoms, declared a state of emergency following the wreckage left behind by Zeta, which was a tropical storm when it hit the city.

"Our findings suggest that as the world continues to warm, the destructive power of hurricanes will extend progressively farther inland," the researchers said, according to Nature.

Kevin Byrne is an AccuWeather staff writer

Comment: Weather is not produced from just moisture, temperature and air pressure. A possibility that has been studiously ignored is the Electric Universe model of weather. The Earth's atmosphere contains different electrical charges at different altitudes. The interaction of these layers, plus inputs from solar winds, have a great deal to do with weather.