Bony fish, such as salmon and tuna, as well as almost all terrestrial vertebrates, from birds to humans, have skeletons that end up made of bone. However, the skeletons of sharks are made from a softer material called cartilage - even in adults.

Researchers have long explained the difference by suggesting that the last common ancestor of all jawed vertebrates had an internal skeleton of cartilage, with bony skeletons emerging after sharks had already evolved. The development was thought so important that living vertebrates are divided into "bony vertebrates" and "cartilaginous vertebrates" as a result.

Among other evidence for the theory, the remains of early fish called placoderms - creatures with bony armour plates that also formed part of the jaws - shows they had internal skeletons made of cartilage.

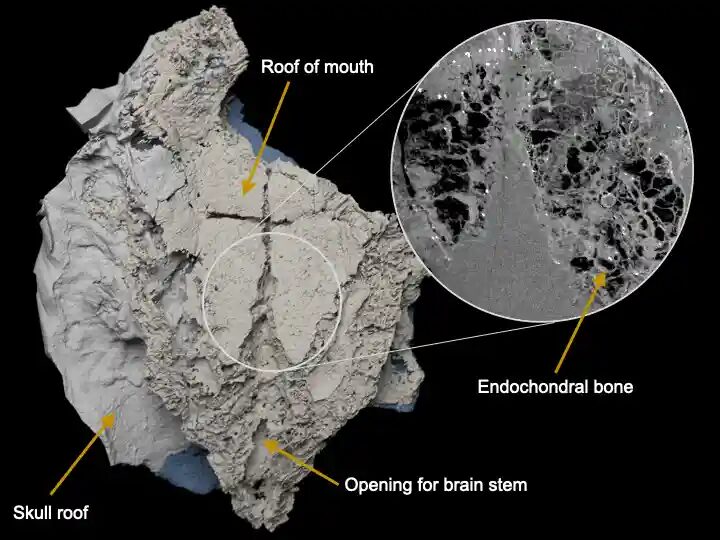

But a startling new discovery has upended the theory: researchers have found the partial skull-roof and brain case of a placoderm composed of bone.

The fossil, about 410m years old and reported in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, was unearthed in western Mongolia in 2012, and belongs to a placoderm that has been dubbed Minjinia turgenensis and would have been about 20-40cm in length.

"This fossil is probably the most surprising thing I have ever worked on in my career. I never expected to find this," Dr Martin Brazeau of Imperial College London, first author of the research, said.

"We know a lot about [placoderm] anatomy and we have hundreds of different species of these things - and none of them has ever shown this kind of bone."

The new discovery, he said, casts doubt on the idea that sharks branched off the evolutionary tree of jawed vertebrates before a bony internal skeleton evolved.

"This kind of flips it on its head, because we never expected really for there to be a bony internal skeleton this far down in the evolutionary history of jawed vertebrates," said Brazeu. "This is the type of thing [that suggests] maybe we need to rethink a lot about how all of these different groups evolved."

While the team say that one possibility is that bony skeletons could have evolved twice - once giving rise to the newly discovered placoderm species and once to the ancestor of all living bony vertebrates - a more likely possibility is that an ancestor of sharks and bony vertebrates actually had a bony skeleton, but that at some point in their evolutionary history the ability to make bone was lost in sharks.

Brazeau said the new findings add weight to the idea that the last common ancestor of all modern jawed vertebrates did not resemble "some kind of weirdo shark", as is often depicted in text books. Instead, he said, such an ancestor more likely resembled a placoderm or primitive bony fish.

Dr Daniel Field, a vertebrate palaeontologist at the University of Cambridge who was not involved in the work, welcomed the findings. "Evolutionary biologists were long guided by the assumption that the simplest explanation - the one that minimised the number of inferred evolutionary changes - was most likely to be correct. With more information from the fossil record, we are frequently discovering that evolutionary change has proceeded in more complex directions than we had previously assumed," he said.

"The new work by Brazeau and colleagues suggests that the evolution of the cartilaginous skeleton of sharks and their relatives surprisingly arose from a bony ancestor - adding an extra evolutionary step and illustrating that earlier hypotheses were overly simplistic."

Comment: Could it be that so many of the theories of how particular creatures evolved are being overturned because the mainstream theory of evolution is fundamentally flawed?

- The Probability of Evolution

- Darwinism, Creationism... How About Neither?

- The many wonders of butterflies and how they evolve by design

- New paper confirms trilobite explosion during Cambrian - appeared out of nowhere with no visible ancestors

- In Cambrian Explosion Debate, Intelligent Design Wins by Default

- "Mindblowing" haul of fossils over 500 million years old unearthed in China

And check out SOTT radio's: