This is the first time scientists have ever electrically transformed an entirely non-magnetic material into a magnetic one, and it could be the first step in creating valuable new magnetic materials for more energy-efficient computer memory devices.

The research is published in Science Advances, a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

"Most people knowledgeable in magnetism would probably say it was impossible to electrically transform a non-magnetic material into a magnetic one. When we looked a little deeper, however, we saw a potential route, and made it happen," said Chris Leighton, the lead researcher on the study and a University of Minnesota Distinguished McKnight University Professor in the Department of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science.

Leighton and his colleagues, including Eray Aydil at New York University and Laura Gagliardi (chemistry) at the University of Minnesota, have been studying iron sulfide, or "fool's gold," for more than a decade for possible use in solar cells. Sulfur in particular is a highly abundant and low-cost byproduct of petroleum production. Unfortunately, scientists and engineers haven't found a way to make the material efficient enough to realize low-cost, earth-abundant solar cells.

"We really went back to the iron sulfide material to try to figure out the fundamental roadblocks to cheap, non-toxic solar cells," Leighton said. "Meanwhile, my group was also working in the emerging field of magnetoionics where we try to use electrical voltages to control magnetic properties of materials for potential applications in magnetic data storage devices. At some point we realized we should be combining these two research directions, and it paid off."

Leighton said their goal was to manipulate the magnetic properties of materials with a voltage alone, with very little electrical current, which is important to make magnetic devices more energy-efficient. Progress to date had included turning on and off ferromagnetism, the most technologically important form of magnetism, in other types of magnetic materials. Iron sulfide, however, offered the prospect of potentially electrically inducing ferromagnetism in an entirely non-magnetic material.

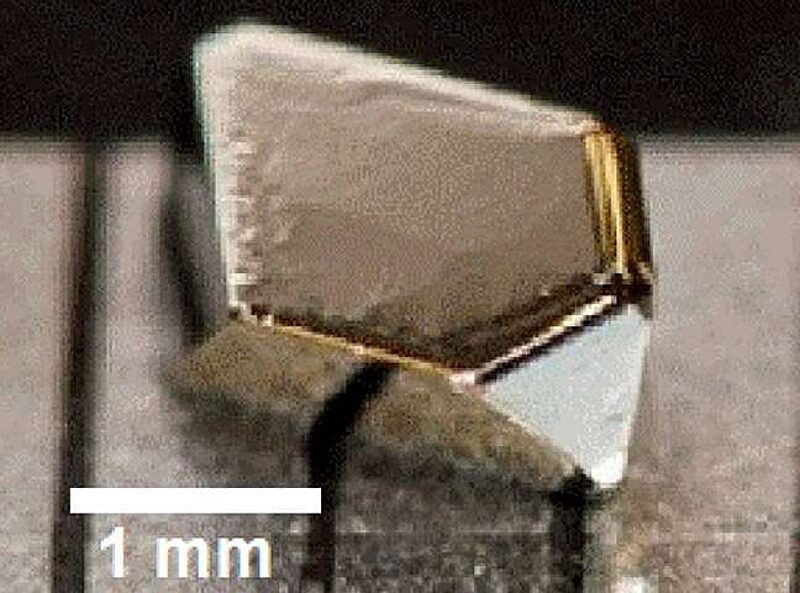

In the study, the researchers used a technique called electrolyte gating. They took the non-magnetic iron sulfide material and put it in a device in contact with an ionic solution, or electrolyte, comparable to Gatorade. They then applied as little as 1 volt (less voltage than a household battery), moved positively charged molecules to the interface between the electrolyte and the iron sulfide, and induced magnetism. Importantly, they were able to turn off the voltage and return the material to its non-magnetic state, meaning that they can reversibly switch the magnetism on and off.

"We were pretty surprised it worked," Leighton said. "By applying the voltage, we essentially pour electrons into the material. It turns out that if you get high enough concentrations of electrons, the material wants to spontaneously become ferromagnetic, which we were able to understand with theory. This has lots of potential. Having done it with iron sulfide, we guess we can do it with other materials as well."

Leighton said they would never have imagined trying this approach if it wasn't for his team's research studying iron sulfide for solar cells and the work on magnetoionics.

"It was the perfect convergence of two areas of research," he said.

Leighton said the next step is to continue research to replicate the process at higher temperatures, which the team's preliminary data suggest should certainly be possible. They also hope to try the process with other materials and to demonstrate potential for real devices.

More information: Jeff Walter et al. Voltage-induced ferromagnetism in a diamagnet, Science Advances (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abb7721

My question is which form of pyrite.?

Also this article is half wrong. Pyrite is para magnetic not non magnetic. Due to a tendency to have granular clusters of crystals instead of a full organized matrix.

Pyrite does have iron in it. Chalco pyrite has copper and iron. Different crystal lattice structures too. Chalco has six sided crystals to ferro pyrites 4

Been a long time I hope I remembered the crystal shaped correctly.