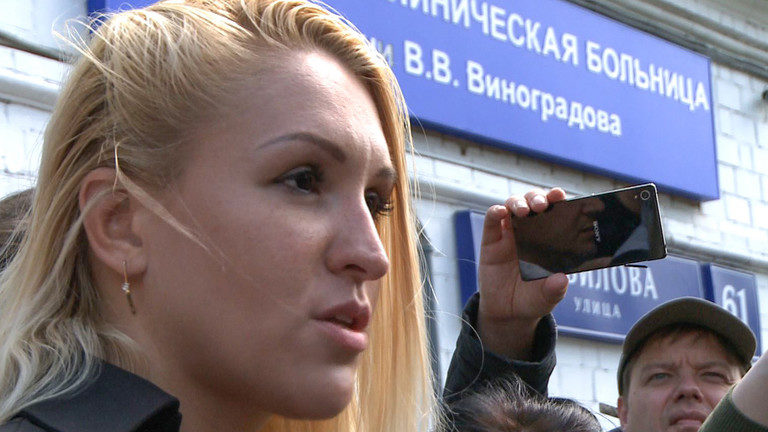

© AFP / AFPTV / Romain COLASAnastasia Vasilyeva

If you know the country well, you will know this: There two Russias - the one 146 million people live in, and the fantasy version Western media outlets describe.

Both exist in parallel universes. This is why most English-speaking Russians usually react with a mixture of shock and horror when their language skills become proficient enough to read what the foreign press is writing about their homeland.

Now, predictably, Russia's response to Covid-19 is being weaponized as part of the mythical 'information war'. This is because Western media coverage of the country generally isn't about journalism; instead, it's about activism. This means that only Russians who fit its narrative are given agency.

For this reason, Alexei Navalny is presented as the "opposition leader," despite the fact there is no united opposition in Russia, and other oppositionists have never selected him to lead them. To make it even more ridiculous, Navalny's support lies at between one and two percent in Russian opinion polls - considerably behind Pavel Grudinin, for example, who basically doesn't exist to consumers of the Western press. Grudinin is a former Communist Party presidential candidate, and when Russian outlets reported that he was blocked from entering parliament (the State Duma) last year, US and UK media essentially ignored his travails, presumably for fear of disrupting its narrative.

To appreciate the strange symbiosis between Navalny and the Western media, we need to look at maneuvering around the Covid-19 pandemic. Eager to attack reaction to the Kremlin's response, some hacks have attached themselves to the Doctors Alliance - a tiny, yet influential, motley crew 'union' of medical workers, closely linked to the man himself. So much so, in fact, that it's led by Navalny's former personal ophthalmologist Anastasia Vasilyeva. On the other hand, Russia's biggest medical union - the Health Workers Union of the Russian Federation (HWURF) - is entirely anonymous in Western coverage, despite its membership totaling around three million.Breaking rulesFirst, a disclaimer: A politically active workers union is nothing bad. In fact, it is undoubtedly a positive - as is any desire to help out a medical system that is often critically understocked and has the potential to be entirely overwhelmed by the coronavirus.

The fact is, after almost three decades of hyper-neoliberal economics - initially egged on by the West - working conditions for doctors in Russian state hospitals are generally poor. What's more, nobody can deny that many hospitals in the country need a lot of help to get up to a reasonable, acceptable standard. Thus, this argument isn't about unions as a concept, and does not assert that there are no problems with the Russian healthcare system. There are many. Instead, it's about a group of activists masquerading as a 'union', who are not actively seeking to improve the life of doctors. Instead of actually helping out, Vasilyeva's associates seem to be more interested in wooing the West.On April 3, Vasilyeva and eleven other colleagues set off for Russia's Novgorod Region, about 400km away from Moscow, ostensibly to deliver much-needed personal protective equipment for overworked doctors. Vasilyeva's group broke strict quarantine laws, designed to stop the spread of Covid-19, to bring boxes of material - masks, respirators, and suits - to two local hospitals. The funding was collected as part of a new project called the 'All-Russian Medical Inspectorate,' which says it aims to supply doctors with vital equipment.

However, at the entrance to the town of Okulovka, just inside the state (oblast) border, the Doctors Alliance convoy of four cars, with three people in each (so much for 'social distancing'), was escorted by local police to the station, where they were kept overnight.

All because Vasilyeva is the most prominent critic of Russia's response to the coronavirus.

Well, that's what you'd think if you relied on Western media to explain Russia. In reality, the story is quite different. Vasilyeva left her home in Moscow, a city now under strict quarantine with over 6,000 reported Covid-19, on the pretext of providing medical care. As she has no registration in the Novgorod Region (which has 12 registered coronavirus infections), she knew she would be breaking the law before she had even crossed the regional frontier. It was publicly broadcast that Novgorod is presently locked down, due to fear of infection.Thus, it's clear Vasilyeva knew she would be arrested. Indeed, the makeup of her eleven comrades essentially betrays that fact: it included a lawyer, a foreigner, and three cameramen, rather than a full complement of working, unionized doctors.Aside from breaching coronavirus rules, she was also charged with disobeying the requests of a police officer - not getting out of her car and refusing an instruction to come to the police station to make a report. According to the Doctors Alliance, her arrest was "real fascism."

If the goal was just to send equipment to a hospital, she could quietly have done it without breaking the law and creating a scene. All she had to do was simply send money electronically to local volunteers or arrange a special delivery. But it's clear this was about PR. Furthermore, on his personal online blog, Doctors Alliance cheerleader Alexei Navalny posted a document from the Ministry of Emergencies, listing the problems of medical institutions in each region. The PDF detailed issues in many different areas of the country - varying from mild to quite severe - and is an eye-opener to the difficulties Russia is facing in its battle against coronavirus. But Novgorod Region, where Vasilyeva went? No shortages reported. Presumably, the likes of Tomsk, Arkhangelsk, and Astrakhan - which appear to urgently need help - are too far away to be worth the effort for these activists.

Subsequently, the head physician of the Borovichi Hospital (one of the two hospitals Vasilyeva supplied), recorded a video explaining that he did not know the original source of the equipment. "Anastasia arrived from the city of Moscow, where there are mass quarantine measures regarding the infection of Covid-19, without any precautions. At the same time, she allegedly brought humanitarian aid in the form of medical masks. Again, it is not clear from which warehouses these masks are from. They had neither certificates nor registrations," Vadim Ladyagin said. Another head physician in Novgorod Region, Natalya Usatova of the Valdai Central District Hospital, told regional website 53 News that the local doctors didn't understand Vasilyeva's actions.

"If we actually did not have enough special protection, this could be done differently. This is a provocation - there is no other name for it. We, the doctors, did not understand this trick. Even we don't allow ourselves to move around the region," Usatova said. "After all, it is possible to clarify with the minister what we need and to involve volunteers in this work. The entire process in the region to combat coronavirus is controlled personally by the minister and the governor."Una voceDespite these facts, Vasilyeva immediately used her arrest as a pretext to engage with foreign media outlets. Vasilyeva spoke with the Associated Press, who uncritically titled their piece "Russia detains activists trying to help hospital amid virus." She told the news agency that the arrest "was about breaking [her]."

Next, Vasilyeva chatted to the Moscow Times - which, despite the name, is a Dutch title, not a Russian one. She told them that she was taking the government's work into her own hands.

The New York Times also picked up Vasilyeva's story, with its headline suggesting that she was detained after questioning official numbers - ignoring her illegal and unsafe quarantine-breaking. The Doctors Alliance was also quick to get in contact with US state media. Unsurprisingly, RFE/RL painted Vasilyeva as a hero. However, perhaps most impressive is Vasilyeva's penchant for bringing foreign journalists along on her journeys. On her trip to Okulovka, she took Steven Derix from

NRC Handelsblad, a well-known newspaper in the Netherlands. According to Derix, she was driving without the correct documentation. Presumably, she just forgot to bring it with her.

In January, the Doctors Alliance took another Western journalist on a trip: Marc Bennetts of the UK's Times newspaper. Vasilyeva brought Bennetts to the small Urals town of Bogdanovich, where there was (coincidentally) another clash with the cops. Before arriving in the Sverdlovsk Region town, she made a public statement about the intention of hospital workers to start a strike in response to the poor working conditions. In reality, there was no strike of medical personnel at all - just four laundry workers, in their admittedly awful and run-down laundry room. According to the hospital management and officials of the regional Ministry of Health, there were also no complaints from doctors. Even Navalny's video of the strike showed the small size of the disgruntled workforce.

Like so many of Russia's hospitals - especially in poorer remote towns and cities - Bogdanovich's is clearly in need of repair.

While nobody would argue that the Russian healthcare system does not need a huge boost, the question remains: If the Doctors Alliance is really a union, and the goal is to draw mass attention to the problems of the healthcare system, why not bring a Russian journalist?The inclusion of Bennetts on Vasilyeva's Urals jaunt could lead one to believe that the Doctors Alliance is not a trade union at all - but a vehicle to show foreigners how much Russia sucks.

After all, how does an article - in English, not Russian - carried by a British newspaper, advance the cause of improvements to healthcare in the Urals, thousands of miles from London? Especially given that the Times is paywalled, with its content available only to subscribers. How many people in Moscow, let alone in the Sverdlovsk region, were likely to see the report?Elephant in the roomRussia has some huge and established medical unions, so why is Western media pushing a fringe activist group with a tiny membership?

Like many countries, Russia is home to several professional trade unions that fight for the rights of their members. Unions are undoubtedly a good thing for workers and offer strong protection against illegal dismissal and abuse in the workplace.

As a rule, unions are stronger when they have higher membership. A broader base means more collective bargaining power, more effective strikes, and a larger pot of money for legal defense. Furthermore, the larger a union is - in general - the more political power it has, and the more press coverage it receives.

Why, then, does the Doctors Alliance and its "small" (by their own admission) membership base receive far more Western media coverage than the HWURF - one of the largest unions in the country?HWURF, with an estimated three million members, is part of the European Public Service Union (EPSU), a group which brings together trade unions from across Europe to influence the policies and decisions of governments throughout the continent. Better still, Russia's health workers don't just play a token role in the continental union - one of its vice-presidents is Mikhail Kuzmenko, the Russian union's chairman.

A quick English-language Google search for HWURF brings up almost nothing, but a search of Doctors Alliance leads to thousands of results. Why is this? The answer is simple - Doctors Alliance is an activist group supported by Alexei Navalny's FBK, which suits the narrative the foreign media likes to cultivate about Russia. In the last month, multiple media outlets such as the Washington Post, NPR, the Times, and the New Yorker have anointed them as an 'independent union', and they've even fooled Lotte Leicht, the EU director of Human Rights Watch.To be fair, at times, some publications have been entirely upfront about the anti-government bias of the 'union'. A New York Times piece from May 25, 2019 mentioned the group's affiliation with Navalny - calling him "Russia's main opposition politician." Of course, Navalny himself retweeted this compliment.

So, who ARE the Doctor's Union - and who is Anastasia Vasilyeva?

A cursory Yandex search (in Russian) quickly brings up lots of smears about Vasilyeva and her PR-loving doctors. They won't be repeated here, as this piece is not about her; it's about the Western media's reporting. So, let's stick to the known facts.

In 2017, Alexei Navalny was attacked by a man who sprayed a caustic green antiseptic at the protest leader. The reprehensible attack was a bad moment for Navalny, but a moment of opportunity for Vasilyeva, who worked as his ophthalmologist. According to Vasilyeva, in early 2018 her mother was fired from her position at a medical research university in Moscow, and she went to Navalny for help. Navalny offered his lawyers, and her mother got her job back. This was the beginning of a brand-new partnership, and they clubbed together to take the Doctors Alliance nationwide.

However, it seems real doctors are just not that interested in the work of the 'union'. According to an

Economist article from May 2019, the Alliance only has 500 members, and their website states that they have 31 different branches throughout the country. However, they must be somewhat low on staff, as, according to their website, Vasilyeva is the regional representative for at least 15 of those branches - ranging from Kamchatka to Crimea, and from Kaliningrad to Magadan. The distance between the latter pair is over 11,000km, by road.

There's not a real union on earth which would expect a 'local organizer' to cover that sort of ground. This is a clear example of why the Doctor's Alliance has no practical domestic utility.Ignored in RussiaWith their continual wooing of the West, a casual follower would be forgiven for believing that the Doctors Alliance has already conquered Russia, and international attention is the next frontier. This is, of course, demonstrably false. Although Navalny and Vasilyeva have Western correspondents in Moscow at their beck and call, Russian media doesn't seem all that interested.

While foreign journalists clamor to write full feature-length profiles of Vasilyeva and her fellow activists, they only seem to pop up in Russian media when staging provocations. Even opposition-leaning outlets such as Echo Moscow and Novaya Gazeta don't seem to care. For example, the Echo print article about Vasilyeva's recent court case was only two paragraphs long, although she does appear quite often on its sister radio station. The New York Times' piece about her arrest? 29 paragraphs. What about ordinary Russians on the internet? Well, despite their polished online presence, the Doctors Alliance has a somewhat abrasive style towards those who ask questions - especially those who query the finances. One VKontakte user was blocked by the union after asking for the names of the equipment suppliers, and to see the receipts.

Despite their shadiness, and zero domestic support, it seems the goal of Navalny and Vasilyeva has been achieved: international acclaim and popularity. The plight of the union has attracted attention across the globe.

Former Estonian president, and erstwhile US state media reporter, Toomas Hendrik Ilves tweeted his support for Vasilyeva, hinting that her April 2020 arrest was due to her questioning the Kremlin's official Covid-19 figures.

Britain-based INGO Amnesty International was also conned by the group, believing that the Russian authorities "fear criticism more than the deadly Covid-19 pandemic." The Amnesty article omitted many critical aspects of the case, distorting the picture in favor of Vasilyeva.

While the union is essentially unknown within Russia, and to speakers of the Russian language, its fame has gone global in the anglosphere. Despite the fact it has little support in the medical community and has achieved no real change, Vasilyeva and the Doctors Alliance have won. The Western press is eating out the palm of their hand, and that's the real objective. Once again, there two Russias: the one 146 million people live in, and the fantasy version Western media presents to its readers.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter