© traveler1116/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

A new analysis of historical archives, local knowledge, and archeological discoveries in El Manchón, Mexico supports the idea that Spanish

invaders, desperate for bronze artillery, bargained, bribed, and subjugated local indigenous peoples, to gain specialised knowledge on metallurgy that the conquerors themselves lacked.

"We know from documents that the Europeans figured out that the only way they could smelt copper was to collaborate with the indigenous people who were already doing it,"

says archaeologist Dorothy Hosler from MIT.

"They had to cut deals with the indigenous smelters."

Historical and archival material from Portugal and Spain have long suggested this was the case, and there appears to be ample archaeological evidence to support this, such as hybrid smelting furnaces reflecting a mix of European and indigenous knowledge.

© Dorothy HoslerA hearth from one of the Mesoamerican smelting furnaces.

According to the team, archival research reveals the Spaniards who arrived in these new lands in the early 16th century

had no knowledge of copper smelting - a practice that had already ended in Spain - and so the invaders were forced to rely heavily on the enemy they were seeking to colonise.

Reports brought back to Spain document novel colonial metallurgical practices that incorporate the use of indigenous iron tools with European bellows and forges.

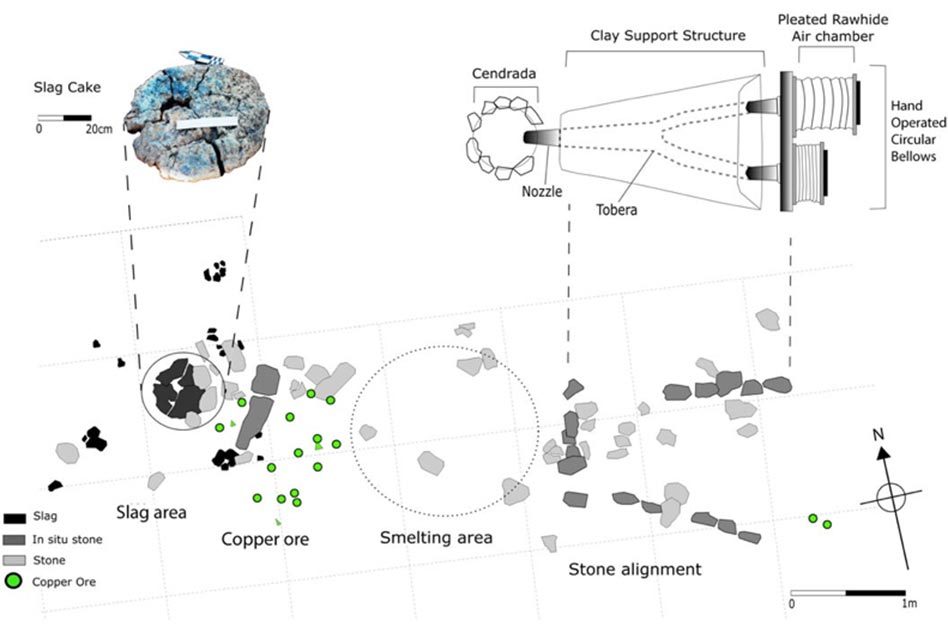

"Our archaeological evidence at El Manchón provides a singular example," the archaeologists

write, "a hand-powered circular bellows furnace design solution that provided one highly successful and long-lasting technical option to increase dramatically the volume of copper production."

It's the only existing archaeological example of this particular design, although an illustration exists in a museum in the area.

Hosler

says that's what's so interesting to her: "We were able to use traditional archeological methods and data from materials analysis as well as ethnographic data" from the furnace to support historical and archival material from centuries ago.

For at least one century and likely for two, Spaniards in Mesoamerica appear to have been dependent on indigenous Mexican miners, builders, and furnace operators - forced to negotiate with the enemy to obtain copper metal for their artillery."The west Mexicans had already developed the technical know-how to smelt these metallic ores," the authors

write.

"What changed dramatically was the scale of copper production, made possible by the introduction of European bellows."

© Dorothy HoslerDiagram of excavation site at one of the indigenous smelting furnaces.

Using four lines of inquiry, including history, engineering analysis, archaeological data, and ethnographic data, the team documented changes in copper production technology in this part of the world across two centuries.

People, of course, have lived in El Manchón for much longer than that, smelting copper ore since at least AD 1630 and probably much earlier, although archaeological evidence is scant.

The

new research suggests the region may have practised it for more than 400 years, spanning prehispanic, early colonial, and late colonial periods. It's just that when the Spanish arrived, there were clear changes to smelting practices.

"We can only imagine the shattering consequences to indigenous smelters and others, when suddenly, copper and other metals, divine and powerful materials, materials that represented and evoked the supernatural, were used for artillery and coins - the same artillery used to oppress these west Mexican peoples and others," the authors

conclude.

The study was published in

Latin American Antiquity.

I read some chronicle somewhere where it was claimed that one of their horses was decapitated by a obsidian sword. They were brittle, but easily made.

R.C.

*They've never found smelt forges/furnaces, nor remnants.. However, smelt have been found around the N. Atlanti and Pacific coasts. However, the researchers never kept any for proof. Why? They smelt. (Sorry.)